When You Say Nothing At All

The spectre of silence looms large over Pranab Mukherjee’s narrative on the events of the tumultuous Seventies.

Pranab Mukherjee had a ringside seat to observe how these profound changes were reflected in the corridors of power.

Pranab Mukherjee had a ringside seat to observe how these profound changes were reflected in the corridors of power.

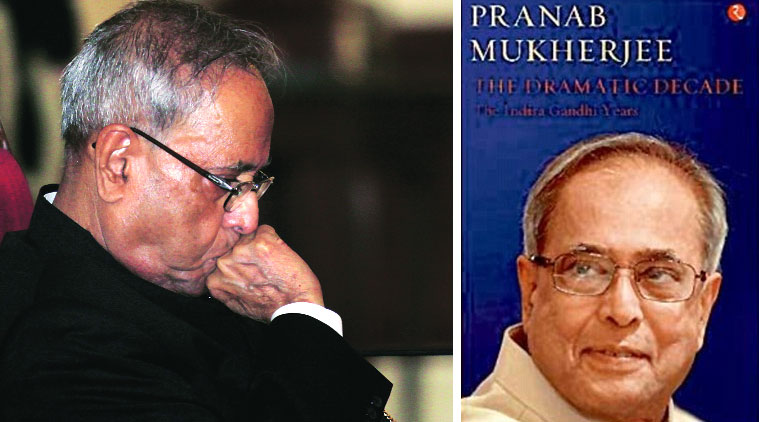

Book: The Dramatic Decade: The Indira Gandhi Years

Author: Pranab Mukherjee

Publicatin:Rupa Publications

Pages: 348

Price: Rs 595

We sometimes suspect that books by politicians are ghost-written because we find an unexpected degree of coherence or literary flair in them. Pranab Mukherjee’s The Dramatic Decade makes you think it must be ghost-written for entirely the opposite reason: it says almost nothing. The Seventies was truly a dramatic decade. It witnessed the creation of Bangladesh, the rise of mass movements like Jayaprakash Narayan’s, strong labour and agrarian unrest, agricultural transformation due to the Green Revolution, industrial stagnation, the experience of authoritarianism and crumbling institutions, heady times in global politics with the CIA actively undermining left of centre regimes, intensifying state control of the economy and so forth. Pranab Mukherjee had a ringside seat to observe how these profound changes were reflected in the corridors of power. Even as a junior minister, he was a significant factor in these processes. He had access to power. He is a gifted politician who has managed to stay at the centre of power without having any real political base, no mean achievement. And yet he has almost nothing to reveal. Nor does the book reflect upon the Seventies in any meaningful way. It is hard to believe he actually wrote the book.

The book’s opening chapters deal with the creation of Bangladesh in a very textbookish way. The rest of the dramatic decade is not framed around dramatic historical forces. It is framed around one drama: the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi. As the Epilogue touchingly puts it, “Indira Gandhi, India’s first woman Prime Minister, and one who had her finger on the pulse of the masses, was voted out by an unforgiving populace after the Emergency. But then reminded of her vision of development and progress, her commitment to the cause of the poor and the disadvantaged and her ability to equally take the rough with the smooth and not waver, the people of India decisively brought her back to power in 1980.”

Although he concedes that the Emergency may have been a mistake for which Indira Gandhi paid a price, the main narrative is structured around loyalty to Indira Gandhi. The only virtue Mukherjee projects is his unwavering loyalty. This, too, was an act of filial piety. His father gave him a poignant piece of advice in 1978, “I hope you will not do anything that will make me ashamed of you. It is when you stand by a person in his or her hour of crisis that you reveal your own humanity. Don’t do anything that will dishonour your father’s memory.” And Pranab Mukherjee’s equally emphatic gloss, “I didn’t, then or later, waver from my loyalty to Indira Gandhi.”

Loyalty is indeed an admirable virtue. But you get no sense of the strains it might impose, the tensions it creates in heady political times. Can there indeed be a conflict between loyalty to party and loyalty to country? Most of Mukherjee’s judgements are structured around loyalty. The book is open in its contempt for Siddhartha Shankar Ray, the architect of a Bengali Congress brand of authoritarian politics. It was he who tutored Indira Gandhi and indicated that she had the legal option of imposing emergency. But when the Shah Commission was appointed, these very people sought to distance themselves from Mrs Gandhi’s actions, denying any knowledge. Mukherjee focuses a lot on the factional fights within the West Bengal Congress, but again almost entirely as a play of personalities, factions and loyalties. You would get little sense of the dramatic street violence or the agitational backdrop against which this politics was conducted.

Mukherjee has also been stingy in sharing insights into how government functions. He admires JP, but thinks he was a moral dupe, throwing in his lot with a bunch of opportunistic politicians of the Janata Party. What would they know of loyalty? JP was also intransigent, and forgot that politics is a play of personalities, not principles.

There are moments of injured innocence, that you suspect speak to the last five years more than the Seventies. When the “bhrastachar hatao” movement was at its peak, he writes, “mere allegations were enough to write people off.” After all, Mukherjee was an anti-corruption crusader. He recounts, without a trace of irony, that his biggest achievement as a minister was to order more crackdowns on tax evaders, smugglers and hoarders of black money. You will get a keen sense of how the license permit raj became a raid and search raj. Mukherjee does concede that these measures did not quite work as expected. So his biggest innovation in the Seventies was the Voluntary Disclosure Scheme, something he seems rather proud of. Those few pages unwittingly give you some insight into what might have gone wrong with Mukherjee’s disastrous tenure as Finance Minister: he sees development policy largely as a series of administrative actions, often arbitrary.

The historical recounting of the Seventies has been better served by bureaucrats. Books like DP Dhar’s asked some hard questions about the aftermath of the Bangladesh crisis. The political economy of the Seventies has also been well served. But its politics still remains elusive, in the absence of declassified papers and good political memoirs. To get a glimpse of the real politics, two of the few sources are the declassified KGB and CIA archives (with all the caveats that apply to such sources). It is there that you find the real world of Indian politics: for instance, the intricate connections between the political economy of tobacco in Andhra Pradesh and the geopolitics of the rupee-rouble trade; the mechanisms by which unions were busted, newspapers intimidated and intrigues hatched, and many innocents denounced as spies on the floor of Parliament. In those pages and episodes, Pranab Mukherjee emerges as a rather more interesting character, though not in any significantly incriminating way. We had expected him to be discreet. But his self-effacing modesty and refusal to engage with history ring so false that it is hard to believe he wrote this book.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta is president, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05