Who is Manikarnika?

In many ways, Manikarnika, better known as Rani Laxmibai, was a reluctant heroine of the Mutiny, who happened to be at the wrong place at the right time.

Born in Varanasi in a Maharashtrian Brahman family of Moropant Tambe, in November 1835 (by most accounts), Manikarnika was the original name of Laxmibai, who took the latter name, upon her marriage to the Maharaja of Jhansi. Her father was a courtier and adviser to the Peshwa of Bithur which is why her childhood was spent in the palace. But as a child she was indeed Manikarnika or Manu, who learned not only to read and write, including reading the Vedas and Puranas, but also riding and sword fighting.

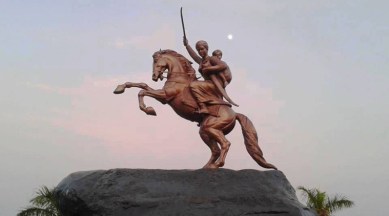

Manu was an excellent horse rider and known to be a good judge of horses. Legend has it that Manu’s companions included Nana sahib, the adopted son of the Peshwa and Tatya Tope, although both were older to her by many years as per their known birth years.

The Doctrine of Lapse was one of Lord Dalhousie’s most important accomplishments in India, as, according to the doctrine, any princely state or territory under the direct influence of the East India Company would automatically be annexed if the ruler died without a direct heir. It was also one of the factors responsible for the 1857 mutiny as it created an unrest among the local rulers, whose reasons for fighting the British differed from those of the Sepoys. The Rani’s appeal to the Company and the British, against Doctrine of Lapse, did not succeed but she was granted a pension and allowed to stay at her residence in the city Palace.

In 1857, the sepoys in Jhansi also mutinied and the British residents in Jhansi, around sixty of them including women and children, were massacred by them. According to many historical accounts, Laxmibai who had been living secluded in her palace without administrative powers is not known to be involved in commissioning the massacre.

The British felt the need to punish the massacre of the Europeans in Jhansi and other places as the they felt the pressing overall need to assert their superiority and control over the Indians, while crushing the rebellion. In 1858, General Hugh Rose arrived in Jhansi leading his forces. It is then that Rani Laxmibai decided to take up arms to arms to defend her state, as it was clear that she has been implicated and made into a scapegoat as much as anyone else. According to J. W. Kaye who authored History of Indian Mutiny of 1857-58, the siege of Jhansi lasted from March 22 to April 5 in 1858.

In many ways, Laxmibai became a reluctant heroine of the Mutiny, who happened to be at the wrong place at the right time. She fought valiantly against the British forces of General Rose in Jhansi and was joined by forces of other rulers. Under the mounting pressure, she was forced to escape overnight from the Jhansi fort on horseback to join other rebels, Rao Sahib and Tatya Tope at Kalpi. Together the rebels managed to take the fortress of Gwalior, an important stronghold in the region and posed the final threat to the British annihilation of the rebellion. Laxmibai was mortally wounded in the battle at Kotah-ki-Sarai while fighting to defend this fortress and with her death one of the last hopes of the rebels also gave out, as Delhi and Oudh regions had already been recaptured by the British by then.

After the end of the campaign in Central India, General Rose reportedly said, “the Indian Mutiny has produced but one man, and that man was a woman.” His words convey the mixed and opposite feeling that the British authors had when writing about Laxmibai; to them she was a mutineer, a rebel and possibly the one who ordered the slaughter of sixty innocent Europeans, but she was also an extremely brave and capable woman, who represented a massive problem for the British army.