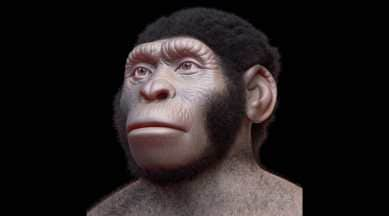

Homo naledi, long-lost human species, buried their dead and carved cave symbols, say scientists

While we already know a lot about the Neanderthals, Homo naledi are a recent discovery.

Palaeoanthropologists have uncovered evidence that suggests that Homo naledi, an extinct human species that lived hundreds of thousands of years ago, may have buried their dead and carved meaningful symbols in a cave. These behaviours were thought to be unique to our own species – Homo sapiens – and the Neanderthals.

These claims were revealed in two research papers uploaded to the pre-print server bioRxiv and were also announced by researcher Lee Berger at a conference at Stony Brook University in New York, according to National Geographic.

The fossils showed a human species that comes with a confusing mix of old and new traits. They walked fully upright just like we do and had hands that were similar to ours. But their shoulders were built for climbing and their teeth were shaped like that of older primates. One of the most interesting things was that their brain size was between 450 to 600 cubic centimetres. – just one-third of that of modern humans

Burying the dead

“Humans are really peculiar as a primate because we bury our dead. No other primate seems to do it,” André Gonçalves, who studies how animals interact with the dead, told National Geographic.

According to Gonçalves, the debate around burying the dead is based on differences between what scientists called mortuary behaviour and funerary behaviour. Mortuary behaviour is evident among chimps and elephants, for example, when they keep watch over a dead body or physically interact with it, expecting it to come back to life.

Funerary behaviours, on the other hand, are social acts by creatures that are capable of complex thought and understand them to be separate from the rest of the natural world. They understand the significance of what death is. Until now, the earliest recorded evidence for funerary behaviour was among both Neanderthals and modern humans, more than 100,000 years after Homo naledi.

But Berger and his research team reported evidence of burials in two locations in the Rising Star system. Homo naledi corpses seem to have been placed in pits that have been dug into the ground, according to Scientific American. The dead bodies were placed in pits that had been dug in the ground and the bodies were then covered with dirt. In one case, the body was arranged in the pit in a foetal position, a common feature of early human burials.

The researchers also described a rock that was almost like a stone tool found next to the hand of the dead body. If it is actually a stone tool or something that was manufactured, it would be the only one associated with Homo naledi discovered so far.

Experts who reviewed the papers for National Geographic have met the reports with scepticism. Some believe that water could have washed the bone fragments into natural depressions in the cave floor, which could have been then filled with sediment over the years.

Writings on the wall

The researchers discovered engravings in the cave in July last year, according to New Scientist.

The team only discovered engravings in the caves in July last year, when Berger entered them for the first time. He had to lose 25 kilograms of weight in order to squeeze through passages in the rock as narrow as 17.5 centimetres wide. “It was incredibly hard to get in, and I wasn’t sure I could get back out,” he says.

In three different areas of the walls inside a narrow chamber within the Rising Star system, the researchers discovered geometric shapes engraved into dolomite stone. They were mainly composed of lines 5 to 15 centimetres long. Dolomite is a relatively hard rock, so it would have taken significant effort to make the shapes. Many of those lines also intersected to form geometric patterns like squares, triangles, crosses and ladder shapes.

“What we can say is that these are intentionally made geometric designs that had meaning. What that meaning is, and how that correlates with, let’s say, different neural cognitive processes for expression of information through oral or other forms of language—we simply don’t know,” said Agustin Fuentes, an anthropologist at Princeton University and co-author of both papers to ARS Technica.

There is a problem, however. The cave’s dolomite limestone walls make dating very difficult and the researchers have conceded that it could be quite challenging to confirm that the engravings happened around the same time as the Homo naledi burials that happened just a few metres away.

But if confirmed, the burials would be the earliest ones yet known by at least 100,000 years. Also, if the drawings were, in fact, made by Homo naledi, and around the same time, it would mean that we would have to rewrite what we know about the evolution of human cognition.