‘Baby quasars!’: Little red dots could be massive breakthrough for Webb telescope

The hunt for these elusive "baby quasars" has just begun, and JWST might be the perfect tool to find more.

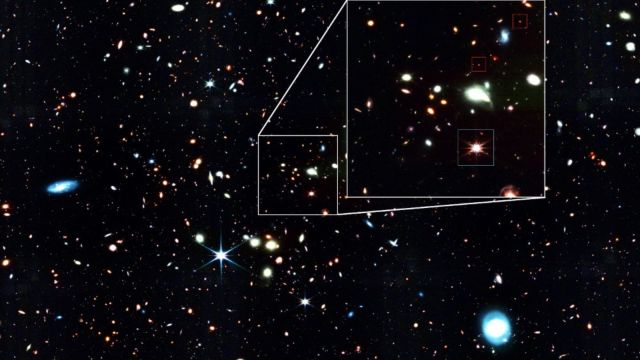

Some supermassive black holes are growing too fast and the Webb telescope may have found the answer to why. (ISTA, NASA, ESA)

Some supermassive black holes are growing too fast and the Webb telescope may have found the answer to why. (ISTA, NASA, ESA)The James Webb Space Telescope could have made one of the most unexpected findings in its first year of operations, said the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) on Thursday. A large number of very faint and small red dots captured from the distant universe could change what scientists understand about supermassive black holes.

These dots are not discernable from normal galaxies to the older Hubble Space Telescope. “Without having been developed for this specific purpose, the JWST helped us determine that faint little red dots–found very far away in the Universe’s distant past–are small versions of extremely massive black holes. These special objects could change the way we think about the genesis of black holes,” said Jorryt Matthee, co-author of a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, in a press statement.

According to Matthee, who is an assistant professor at ISTA, the discovery could help scientists understand one of the biggest enigmas in astronomy. Based on current models, some supermassive black holes in the early universe have grown “too fast.”

Scientists generally agree that there is a supermassive black hole at the centre of all galaxies. In fact, the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to scientists who confirmed that the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* is at the centre of our universe and has four million times the mass of our Sun.

Sagittarius A* is relatively tame and can be thought of like a dormant volcano. But some supermassive black holes grow extremely fast by eating incredible amounts of matter. This makes them so bright that they can observed until the edge of the universe. These black holes are called quasars and are among the brightest objects in the universe.

“One issue with quasars is that some of them seem to be overly massive, too massive given the age of the Universe at which the quasars are observed. We call them the ‘problematic quasars.’ If we consider that quasars originate from the explosions of massive stars–and that we know their maximum growth rate from the general laws of physics, some of them look like they have grown faster than is possible. It’s like looking at a five-year-old child that is two meters tall. Something doesn’t add up,” explained Matthee.

The researchers believe that the red dots they found are “baby quasars” and that studying them will help them better understand how these “problematic quasars” happened to grow.