What Turkey’s neo-Ottomanism means in 2023

While neo-Ottomanism as a concept grew sometime in the late 1980s -1990s, to explain Turkey's geopolitical aspirations, some scholars believe that it was also used as a critical term by some of its neighbours, like Greece for instance, with whom it doesn't share amicable relations.

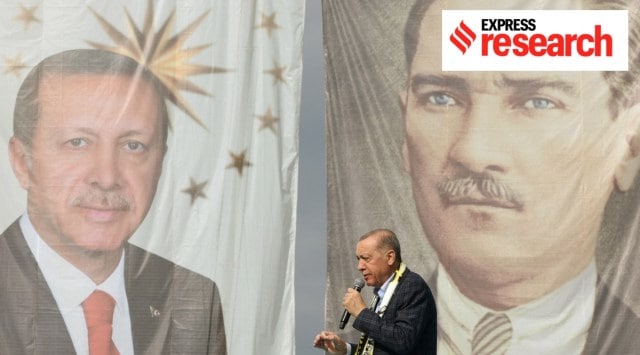

So, what do Turkish President Erdogan's views on neo-Ottomanism mean for South Asia, more specifically India? It is a complex question. India’s relations with Turkey since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1948 have been cordial, Ankara’s support to Pakistan and its stance on Kashmir have been a bone of contention. (Reuters)

So, what do Turkish President Erdogan's views on neo-Ottomanism mean for South Asia, more specifically India? It is a complex question. India’s relations with Turkey since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1948 have been cordial, Ankara’s support to Pakistan and its stance on Kashmir have been a bone of contention. (Reuters) Fourteen years ago, Turkey decided to make pivotal changes in how it looked at the world. Ahmet Davutoglu, then foreign minister, was put in charge of shaping Ankara’s new geopolitical goals to be pursued by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government headed by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Davutoglu’s policy, simply put, involved having “zero problems” with Turkey’s neighbours while maintaining good relations with the West. In 2010, Turkey voted against increased U.N. sanctions on Iran, signalling a shift in its foreign policy which now looked more aligned with its own interests and not of its ally, the United States. For the longest time, Ankara was an important bridge between the Middle East and the European Union. Bolstering ties with Muslim neighbours became Turkey’s new priority.

Foreign policy experts at that time said the shift meant Ankara was now looking to bolster trade and geopolitical agreements in the Middle East, a region with which it had cultural and historic ties dating back to the days of the Ottoman Empire.

Understanding neo-Ottomanism

Since the AKP came to power in 2002, the Turkish government’s foreign and increasingly domestic politics have been characterised as ‘neo-Ottoman,’ a concept which both its critics and champions have wielded in different ways, writes Edward Wastnidge, senior lecturer in Politics and International Studies at The Open University, in his 2019 paper ‘Imperial Grandeur and Selective Memory: Re-assessing Neo-Ottomanism in Turkish Foreign and Domestic Politics’.

He argues that for “at least the past decade, neo-Ottomanism has served as one of the main conceptual tools for understanding Turkish foreign policy. More recently, the concept also has emerged in Turkish domestic political discourses, albeit in a distinct manner from, yet relevant to, its foreign policy equivalent.”

Other experts explain the break from previous concepts like Ottomanism. “Ottomanism was primarily conceived as a reform and renewal project for the declining Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. Most of the proponents of Ottomanism were Europe-returned Turks who wanted to modernise the empire as a cosmopolitan, plural, and modern empire like Japan. Later on, Turkish nationalism was seen as the primary challenge against Ottomanism as Turkish nationalism wanted to make Turkey the nation of only Turks, where Arab and other ethnicities were not welcomed,” explains Omair Anas, assistant professor at Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University’s Department of International Relations in Turkey, in an interview with indianexpress.com.

“However, as globalisation made all nationalisms, including Turkish, more vulnerable, Turkey’s conservative parties saw Islam and Muslim identity as the basis of openness of Turkey to its immediate neighbours. Neo-Ottomanism was conceptualised as ‘embracing globalisation with a non-isolationist regionalism’ as former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu once defined,” adds Anas.

At the end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, several countries to the east and west of Turkey began declaring their independence. This impacted Turkey’s foreign policy, in part because of domestic considerations over the role that Turkey would play in a new world order. Turkey’s former prime minister Turgut Özal who was in office between 1983 to 1989, first used the phrase “Turkish world from the Adriatic to the Great Wall of China”.

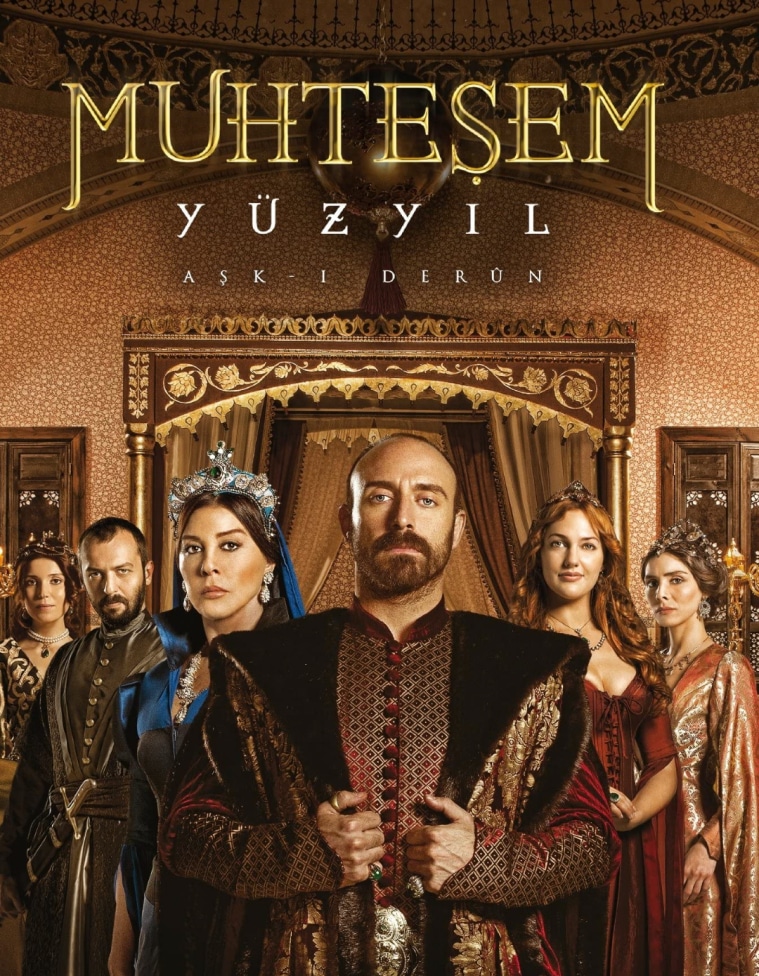

Muhteşem Yüzyıl was broadcasted between 2011-2014 had a global fandom, from Bangladesh to Chile. (Source:IMDB)

Muhteşem Yüzyıl was broadcasted between 2011-2014 had a global fandom, from Bangladesh to Chile. (Source:IMDB)

In his book ‘New World Order and Small Regions: The Case of South Caucasus’, author Emil Avdaliani writes that this concept of the expanse of the Turkish world “was often brought up, as was the model of the Turkish state-building serving as a guiding example for the former Soviet states. Those designs failed to attract because of Turkey’s paucity of economic resources and ultimately the lack of attractiveness of the Turkish model.”

While neo-Ottomanism as a concept grew sometime in the late 1980s -1990s, to explain Turkey’s geopolitical aspirations, some scholars believe that it was also used as a critical term by some of its neighbours, like Greece for instance, with whom it doesn’t share amicable relations.

“Originally, the biggest exponents of Ottomanism in the late nineteenth century were non-Muslim Ottoman politicians — Greeks and Armenians — who wanted to make the Ottoman Empire a secular empire where all religions have equal rights. Many Muslim Ottoman politicians agreed with this. However, Turkish nationalists including Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and Islamists opposed Ottomanism as an impractical idea and rejected it. So, intellectually, neo-Ottomanism should have supported more cooperation with Greece, Armenia, Arab states, and the Balkans. However, neo-Ottomanism was embraced by both nationalists and Islamists. While Islamist neo-Ottomanists favoured openness to Europe, Greece and Armenia, the nationalist-neo-Ottomanists saw Greece and Armenia as the main rival of Turkey,” says Anas.

Geopolitical aspirations

In the discourse over Turkey’s geopolitics, the use of ‘neo-Ottomanism’ has become more frequent after 2020. But Anas says the scenario is different within Turkey. “In reality, rarely do Turkish politicians and Turkish people use this term in their daily political debates. Neo-Ottomanism in its current meaning, a source of threat to regional security and stability, is the creation of western media,” explains Anas.

So, what do Erdoğan’s views on neo-Ottomanism mean for South Asia, more specifically India? It is a complex question. India’s relations with Turkey since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1948 have been cordial, Ankara’s support to Pakistan and its stance on Kashmir have been a bone of contention.

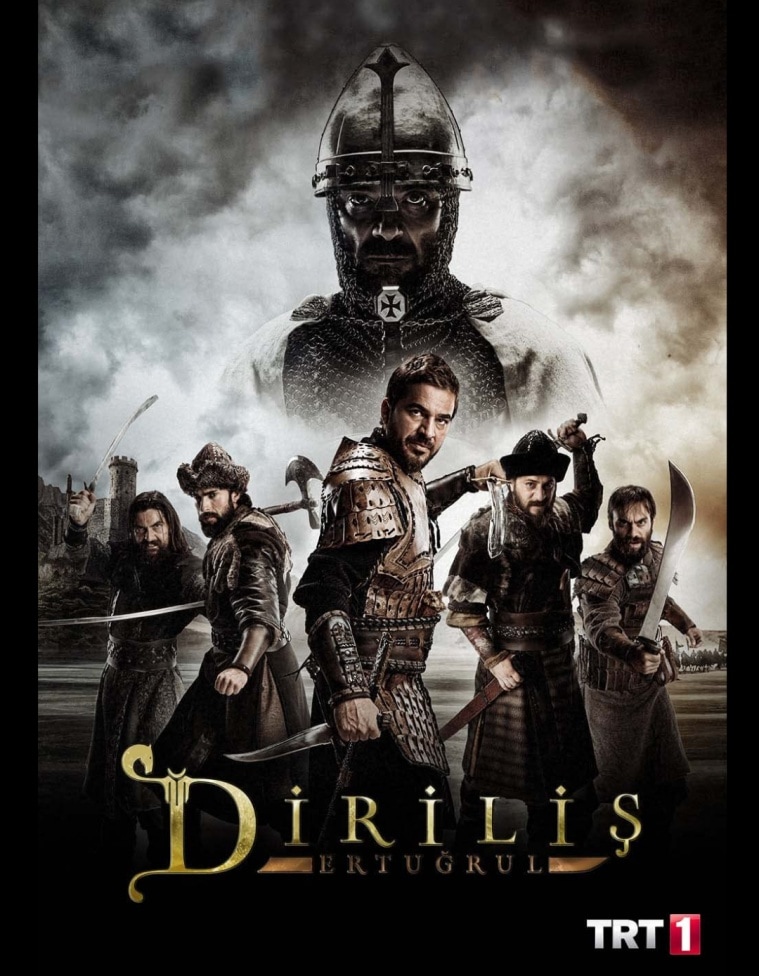

An extremely popular production, Diriliş: Ertuğrul, was broadcast between 2014-2019 and was based on on the 13th century life of Ertuğrul, the father of Osman I, the founder of the Ottoman Empire. (Source: IMDB)

An extremely popular production, Diriliş: Ertuğrul, was broadcast between 2014-2019 and was based on on the 13th century life of Ertuğrul, the father of Osman I, the founder of the Ottoman Empire. (Source: IMDB)

“Originally, neo-Ottomanism should have been more favourable to India, and South Asia in general, as it happened during the last years of the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman politicians were very keen to cooperate with India’s anti-colonial leaders, along with the Japanese Empire,” says Anas. He points to the story of Raja Mahendra Pratap, an Indian freedom fighter from modern-day Hathras, who was the president of the Provisional Government of India – which served as the Indian Government-in-exile during World War I – established in Kabul in 1915. The Provisional Government of India’s primary objectives were to seek support from the Central Asian empires against the British.

“In 1915, the Ottoman Sultan had received Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh and supported his plan to establish an Indian Government in Exile in Kabul under Raja’s presidency. Ottoman and German spies escorted Raja to Kabul,” says Anas. The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 and the Cold War reset relations in the global order, as well as between India and Turkey.

Role of Turkish popular culture

Over the past two decades, Anas says, there has been a significant rise in “public awareness, respect, and sensitivity towards the Ottoman past”. He points to pop culture products like Turkish television dramas, movies and novels on the Ottoman Empire that have been extremely popular, not just in Turkey but also overseas.

Turkish dramas or dizi, like Muhteşem Yüzyıl that was broadcast between 2011-2014 had a global fandom from Bangladesh to Chile. Also called ‘Magnificent Century’ in English, it starred Halit Ergenç in the lead role, and was based on the life of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and his wife Hürrem Sultan, a slave who became the Ottoman Haseki Sultan, the first chief consort of the Ottoman sultan. Another extremely popular production, Diriliş: Ertuğrul, was broadcast between 2014-2019, starring Engin Altan Düzyatan as the protagonist, and was based on on the 13th century life of Ertuğrul, the father of Osman I, the founder of the Ottoman Empire.

Diriliş: Ertuğrul was broadcast on the state-run network TRT, and Erdoğan’s personal interest in the dizi was apparent because of the visits that he made with his family on the dizi’s sets.

Despite the popularity of Turkey’s soft power export, it may not be sufficient to cement Erdoğan’s foreign policy goals, which is essentially to assert regional supremacy. Turkey’s military intervention in northwestern Syria has put it on the opposite side of the Gulf monarchies, although some experts would say that the discord can be traced to 2011 when the Arab Spring occurred. Erdoğan’s attempts to present Turkey as the representative of Sunni Muslims has also resulted in disputes with Saudi Arabia. And Turkey’s support for Qatar means that Ankara now only has Doha as an ally in the region.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05