The ‘Good Maharaja’: When a Gujarat ruler hosted Polish WWII refugees

In an often forgotten chapter of history, during the Second World War, over 6000 exiled Poles found refuge in India. The Maharaja of Nawanagar personally took in 1000 children, paving the path for others to do the same. He provided these children with every amenity they needed but most importantly, against the ravages of war, he gave them a home.

The children called Jamsaheb 'bapu' or father

The children called Jamsaheb 'bapu' or father For 94-year-old Karolyna Rybka, life in Siberia was desperate and unforgiving. Rybka, who now resides in a care home in Edmonton, Canada, was one of the 320,000 Poles deported to Siberia in 1941 during the German and Russian occupation.

One of three survivors from a family of nine, Rybka recalls the days after the start of World War II. “We thought we were going to starve or freeze to death… We’d lost our parents, and no one wanted us,” she tells indianexpress.com over phone. Rybka credits her survival to one man, Maharaja Digvijaysinhji, ruler of the princely state Nawanagar, now in Jamnagar. In 1942, the Maharaja, known as Jamsaheb, opened an orphanage for Polish refugees in Balachadi, a coastal town on the Gulf of Kutch.

Although sources differ, according to Kenneth Robbins, a psychiatrist and scholar of expatriates in South Asia, between 1942 and 1948, over 1000 people, mostly children, were sheltered at Balachadi. Jamsaheb is said to have welcomed them as his own children, saying “you are no longer orphans, from now on you are Nawanagarians.”

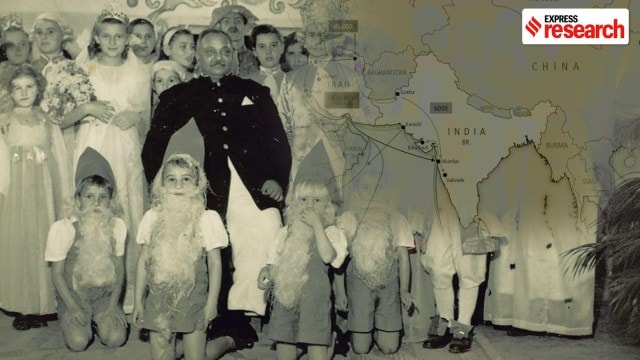

A portrait of Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji Jadeja, Maharaja of Nawanagar (Royal Archives)

A portrait of Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji Jadeja, Maharaja of Nawanagar (Royal Archives)

Maharaja Digvijaysinhji’s actions were recognised by the Government of Poland in 1989, when the newly independent nation named a square after him in Warsaw. During his trip to Poland earlier this month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited the ‘Good Maharaja Square’, along with two other memorials dedicated to people and places in India that sheltered over 6,000 Polish refugees during the Second World War.

Prime Minister Modi’s visit has sparked interest in this forgotten chapter of history, leading many to wonder who was this kind-hearted Maharaja and why did he take in these orphaned Polish children?

Plight of the Polish

On a bitterly cold night in February 1940, teams from the Soviet police force raided thousands of homes along Poland’s Eastern border with Russia. Half asleep families were wrenched from their beds and told that they had anywhere between 15 to 30 minutes to collect their belongings and prepare to leave.

Britain and France had declared war against Germany in November 1939 and were aware that the Nazis had signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviets earlier that year. However, unbeknownst to them and the government of Poland, the now infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact also included a secret provision dividing Poland between the two powers. Unprepared for a Russian attack only three months after Germany invaded western Poland, the country fell quickly, and its government fled into exile.

Between February 1940 and June 1941, anywhere between 320,000 to 980,000 Polish citizens were deported to Russia via cattle cart. In Polish Orphans of Tengeru (2009), Purdue University Professor Lynne Taylor documents the “nightmarish journey” which claimed the lives of many, both young and old. Sent to the depths of the Russian interiors, those who survived were crammed into barracks infested with cockroaches and forced into physical labour. Children as young as ten were assigned gruelling tasks and informed that under Bolshevik principles, those who didn’t work, didn’t eat. Estimates indicate that nearly half died within one year of their arrival.

Swimming competition at the Balachadi settlement, 1946 (Wieslaw Stypula)

Swimming competition at the Balachadi settlement, 1946 (Wieslaw Stypula)

On June 22, 1941, Germany violated the pact, invadeding the USSR and by July, Nazi forces were only 320 kilometres away from Moscow. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was caught unawares and left scrambling to defend his own country. On July 30, in the presence of UK prime minister Winston Churchill, Stalin was forced to grant Polish citizens ‘amnesty’ in exchange for the allied forces recognising the status quo ante borders of Poland. According to a January 1943 note from Soviet politician Lavrentiy Beria to Stalin, 389,041 Polish citizens were freed as a result of that amnesty, many of whom were conscripted into the allied war effort, including general Władysław Anders.

Russia had freed the Polish but considered their responsibility to have ended there. With little support, far-flung Polish exiles began to make their way southward, determined to join General Anders’ fledgling army in the Middle East. Many didn’t survive the journey and those who did, were stranded in transit camps across Soviet-controlled Iran, desperately awaiting a place of refuge.

That’s when we know Jamsaheb stepped in.

Parallels to Indian struggle

It’s possible that Jamsaheb resonated with the Polish cause due to its similarities to the Indian independence movement. Like British Indian citizens, the Poles were devoid of a country of their own, at the mercy of the whims of their occupiers, the Soviet Union.

The Soviets had reluctantly agreed to let refugees into Iranian camps but had made it clear that they wanted little else to do with them. The stranded Poles had no means to support themselves and as technically ‘free’ citizens, were given no assistance by the state. Although Britain had negotiated their release, they had done so under a different premise. As author Kieth Sword notes in The Soviet Takeover of the Polish Eastern Provinces (1991), the British were hoping for young, fit men to bolster their beleaguered forces in the Middle East. However, due to increasingly high mortality rates “instead of getting an army, they were getting a welfare problem.”

The British government was stuck. They had a responsibility to these Polish exiles but also to preserving their precarious alliance with the USSR. Weary of upsetting Stalin, the government made exhaustive efforts to find other countries that would accept the refugees.

None were willing.

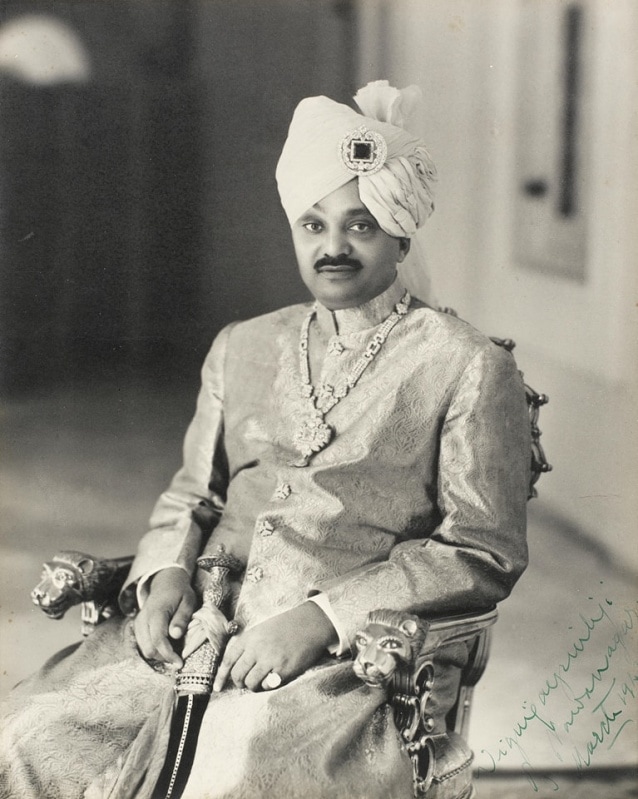

Camp at Balachadi with Polish Flag (Tadeusz Dobrostanski)

Camp at Balachadi with Polish Flag (Tadeusz Dobrostanski)

According to Anuradha Bhattacharjee, author of The Second Homeland (2012), in October 1941, the British government appealed to the Viceroy of India to take in 500 Polish children from the USSR. Negotiations began but were ultimately rejected by both parties. Hearing about this plight during a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet in 1942, Jamsaheb became the first leader to offer refuge. The subsequent creation of the Balchadi camp came out of the “personal generosity” of the Jamsaheb but also, crucially, provided a political model for the British to help Polish people without straining ties with the USSR, says Bhattacharjee in an interview with indianexpress.com. Officially, in the princely states, the refugees would not be in British territory.

In a 2013 article for the Samaritan Review, Bhattacharjee writes that the initiative of Jamsaheb “paved the way for several thousand Polish refugees to be received in various parts of the world” under this model. Robbins adds that it also demonstrated the political agency of the princes, at a time when many considered them to be a puppet of the British state.

Jamsaheb’s own nationalist tendencies are unclear. Robbins states that he was a right-wing figure, dedicated to the preservation of Hindu culture and the promotion of Ayurvedic medicine. “He was a highly underrated person. Politically he was very important and socially, very powerful.” Like many of the other rulers of the princely states, Jamsaheb straddled a thin line between supporting the nationalist movement and preserving his own sphere of influence.

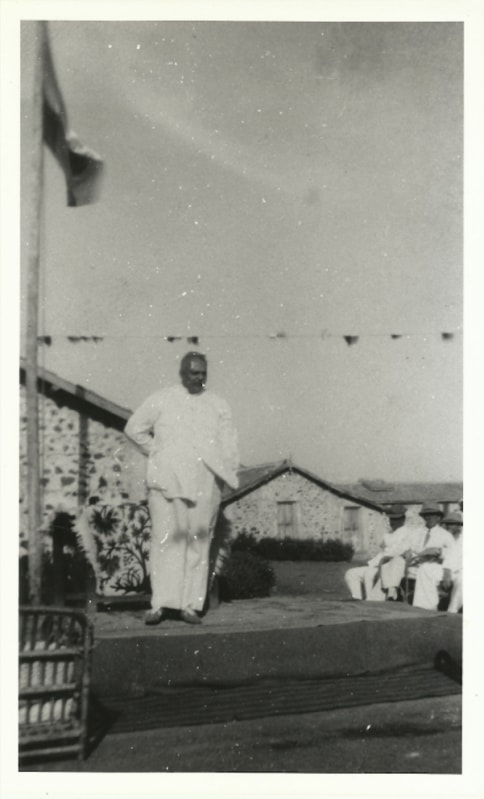

Jam Saheb Digvijaysinhji visiting Balachadi Camp (Tadeusz Dobrostanski)

Jam Saheb Digvijaysinhji visiting Balachadi Camp (Tadeusz Dobrostanski)

According to Robbins, Jamsaheb, who served as the Chancellor of the Chamber of Princes from 1933 to 1944, was concerned about the issue of state sovereignty and once spoke of supporting the Muslim League against the Congress as “Mr. Jinnah is willing to tolerate our existence, but Mr. Nehru wants the extinction of the Princes.” Nevertheless, he was one of the first Indian princes to sign the Instrument of Accession and played a formative role in the “transformation of Western India to a unified part of newly independent India.”

Similarly, on the issue of Polish refugees, the Maharaja proved willing to work with the British, within British systems while maintaining his own agency in his support for occupied people. It helped that he had his own connection to Poland, dating back to his childhood.

Polish connection

Before exploring Jamsaheb’s ties to Poland, it is worth acknowledging the role of Kira Banasińska, the wife of the Polish consul general to India, Eugeniusz Banasiński. Kira was staunchly dedicated to the cause of Polish refugees. Together with Wanda Dynowska, a Gandhian already in India, Kira spread awareness on double occupation in Poland, raising funds and spearheading diplomatic initiatives to ease the plight of her compatriots.

According to Anjali Bhushan, director of My Home India, a film based on Kira, in 1942, neither the British nor the Indians had much incentive to help Polish refugees. Bhushan says that Kira undertook 75 trips across undivided India to secure permission for the refugees to arrive in India and organised their transportation. “She was like a butterfly,” says Bhushan, adding that “she had frequent parties for hundreds of people and made friends with everyone from the Princes to the Tatas.” She was not shy about asking for help for her people and personally implored Jamsaheb to set up the camp at Balachadi.

Chess tournament for youngsters at the Balachadi settlement (Polish History Museum Warsaw)

Chess tournament for youngsters at the Balachadi settlement (Polish History Museum Warsaw)

In addition to his friendship with Kira, Jamsaheb was also acquainted with Ignacy Paderewski, a skilled pianist and former prime minister of Poland. Jamsaheb’s uncle and predecessor was Ranjitsinhji, the famed sportsman who represented England in 15 Test cricket matches. As a child, Jamsaheb travelled with Ranjitsinhji to Paderwski’s estate in Switzerland. As recounted by author Imogene Salva in One Star Away (2020), during a 1922 visit, Jamsaheb played one of Frédéric Chopin’s compositions on Paderwski’s grand piano. Denouncing the prince as being “tone deaf,” Paderwski instructed him to channel the emotions of Chopin and his despair over Poland’s occupation during the 19th century.

By then, through his association with Paderwski, “the young prince Digvijay Sinji decided he very much liked Poles and Poland.” Although the country was free at the time, Paderwski warned that Poland’s geography meant that it was always in a precarious position and its people constantly prepared to defend their nation. To this Jamsaheb is said to have responded, “your nation, which has known centuries of persecution and whose fields and cities have been often drowned in blood, will always rise again like a phoenix.”

Jamsaheb’s dedication to Poland was put to the test in 1942.

As Robbins argues, at the time, Indian maharajas accepted refugees based on practical concerns. Patiala took in much-needed physicians and Mysore, a famed architect. However, the orphans at Balachadi provided little present value. Instead, Jamsaheb took them in with the hope that they could one day rebuild their lost nation. In an interview to a weekly magazine Poland, Jamsaheb explained why he offered the children shelter: “I am trying to do whatever I can to save the children; as they must regain their health and strength after these dreadful trials, so that in the future they will be able to cope with the tasks that await them in a liberated Poland.”

A Young Boy’s Holy Communion Service in Balachadi (Polish History Museum)

A Young Boy’s Holy Communion Service in Balachadi (Polish History Museum)

As a result of these intentions, great emphasis was attached to maintaining patriotic and religious instruction at Balachadi. Bhushan states that Polish tradition and identity was immaculately ingrained with life at the camp. The children studied under a Polish education system, unveiled the Polish flag daily, had their own food and spoke primarily in the Polish language.

Unfortunately, Poland remained under Soviet influence until 1989, and most of the exiled children never got the chance to return to their homeland.

Whether due to his own nationalism, his love of Poland or simple humanitarianism, Jamsaheb was undoubtedly a hero to hundreds of Polish children. However, not much is known about him, and even leading scholars of Polish refugees in India are unable to form a consensus on his actions or motivations.

Jamsaheb and the Balachadi camp

Experts and historians interviewed for this story recognise the Maharaja for his act of benevolence, and his importance in not only being the first to welcome Polish refugees but also for advocating on their behalf to the regent of Kolhapur who eventually established a camp at Valivade that sheltered and additional 5,000 people. Sources differ on who primarily facilitated the influx of refugees — Jamsaheb, Kira, the Polish government in exile or the British — but few discredit the contribution of the Maharaja.

What is however more in question, is his role in financing and administering the camp. Bhattacharjee argues that the Balachadi camp was constructed by the Jamsaheb through his personal fortune and with donations that he facilitated. Robbins however states that the Polish government in exile paid for the construction of the camp. Its day-to-day activities were paid for by the British government with the understanding that the same would be repaid to them by the Polish.

Diagram of the Balachadi settlement, drawn by Wiesław Stypuła in the 1980s

Diagram of the Balachadi settlement, drawn by Wiesław Stypuła in the 1980s

Filmmaker Anu Radha, who produced the movie Little Poland, which was co-produced by the Government of Gujarat, says that Jamsaheb was a “father” to the children and was “extremely involved in all their day-to-day activities, be it games (football), medical care, education and XMas parties to which he was their Santa Claus.” She has extensively interviewed his daughter, Hershad Kumari, who stated that her father asked her to treat the Polish children like their own brothers and sisters. Hershad and her family have hosted many of the Polish survivors since they left India. However, various first person accounts seem to cast some doubt on these claims, with many of the children mentioning that they only met Jamsaheb a handful of times.

The facility at Balachadi was constructed at Jamsaheb’s summer resort in Nawanagar. The camp had more than 60 buildings including a chapel, laundry room, schools, a kindergarten, an auditorium, two medical facilities, sporting grounds and a community centre. Jamsaheb also permitted the children to use his swimming pool and tennis courts. He appointed the wife of his Aide-De-Camp (ADC) to coordinate any special requests and on a few occasions gifted money directly towards the purchase of sporting equipment and musical instruments. Some children were invited on occasion to his summer palace and in 1942 he sent them three camel loads of gifts for Christmas.

According to Bhattacharjee, “he definitely kept a benign eye on the camp.”

In 1945, the Soviets falsified an election in Poland and declared the country to be under communist rule. When representatives of the new Polish government said that under international law, the exiled orphans were to be repatriated to Poland, there was marked resistance amongst the children. According to Bhattacharjee, they did not want to become wards of the new Polish state that was heavily skewed in favour of the USSR.

Maharaja Digvijaysinhji with children from the Balachadi settlement (Wieslaw Stypula)

Maharaja Digvijaysinhji with children from the Balachadi settlement (Wieslaw Stypula)

As orphaned children were forced to return, Jamsaheb formed an adoption council with his ADC and Father Pluta, the Balachadi camp commandant. Between the three, they legally adopted 86 children who were then placed in missionary schools across the United States. It is unclear whether Jamsaheb financed their journey.

Despite these discrepancies, the actions of Jamsaheb have been commended by the Polish government. In addition to the ‘Good Maharaja’ square in Warsaw, there is also a private school named after him. It was a fulfilment of a request he had made decades earlier. When Władysław Sikorski, Prime Minister of the Polish Government-in-exile had asked Jamsaheb how they could thank him for his generosity, he replied, “You could name a school after me when Poland has become a free country again.”

Perhaps his greatest legacy is the feeling of security he provided the children. In her book, Taylor writes about one such child that she interviewed, Kazimiera Mazur. Just before Mazur was supposed to come to India from Tehran, her younger sister Margie fell ill. Mazur, the oldest child, had been entrusted by her mother not to let her younger siblings be separated. However, when Margie was hospitalised, Mazur was forced to leave her behind.

Upon arriving in Jamnagar on December 8, 1942, Mazur was devastated to have abandoned her sister. However, five months later, a truckload of children arrived at the camp and although Mazur didn’t expect to be reunited with Margie, she desperately hoped that she would. “But she came with the other group of children,” Mazur recollects, “and said to me in Russian, ‘take me in your arms because I am tired’.” Only four-and-a-half at the time, Margie remembers nothing of her mother or of Poland today. The first thing in her life that she remembers is arriving at Balachadi, of reuniting with her sister, and of finally feeling as though she had a home.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05