The bloody history behind how Israel, and Palestine, came into existence

The Israel-Palestine conflict, a century-old struggle over a tiny but historically significant region, remains steeped in religion, politics, and shifting borders. Covering Biblical times, Ottoman rule, British occupation, Arab-Israeli wars and decades of conflict, the ever fluid boundaries of Israel reflect the shifting tides of power politics in the Middle East.

An archive image of Israeli settlement (Source: Wikimedia Commons/PikiWiki/ דוב ורדי)

An archive image of Israeli settlement (Source: Wikimedia Commons/PikiWiki/ דוב ורדי) The conflict between Israel and Palestine began just under a century ago, but the significance of the land precedes even Biblical times. The area in question covers a tiny swathe of the Southern Levant, bordering Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea. With perpetually shifting borders, accusations of segregation and claims of historical significance, the region has served as a fierce battleground between Jews, Arabs, and Palestinians, backed by a rotating cast of states including the UK, America, France, Iran, and Turkey.

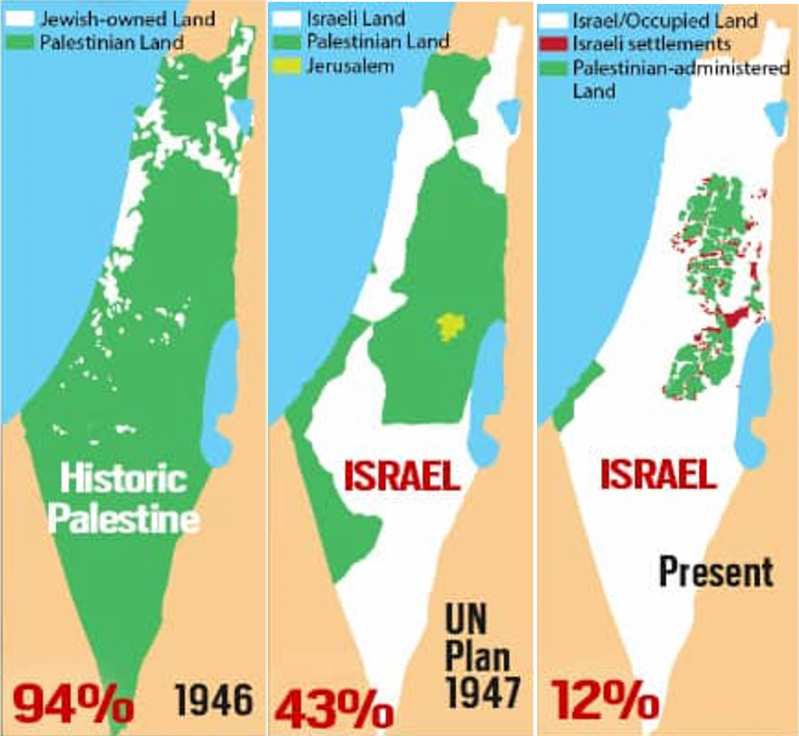

While 165 member states of the United Nations refer to the region as Israel, the remaining 30 do not recognise Israeli statehood and refer to the land as Palestine. Of the states that recognise Israel, all accept that the Jewish settlements and segregationist policies constitute a form of forced occupation. At present, most of the West Bank is administered by Israel although approximately 42 per cent of it is under various degrees of autonomous rule by the Palestinian Authority. The Gaza Strip, a 41-kilometre-long and 10-kilometre-wide strip of land located between Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, is currently under the control of Hamas which is designated as a terrorist organisation by the United States and European Union.

The Holy Land

Although many consider the conflict between Israel and Palestine to be one of territory not religion, it is impossible to understand the historical significance of Israel without touching upon its importance to Judaism and Islam.

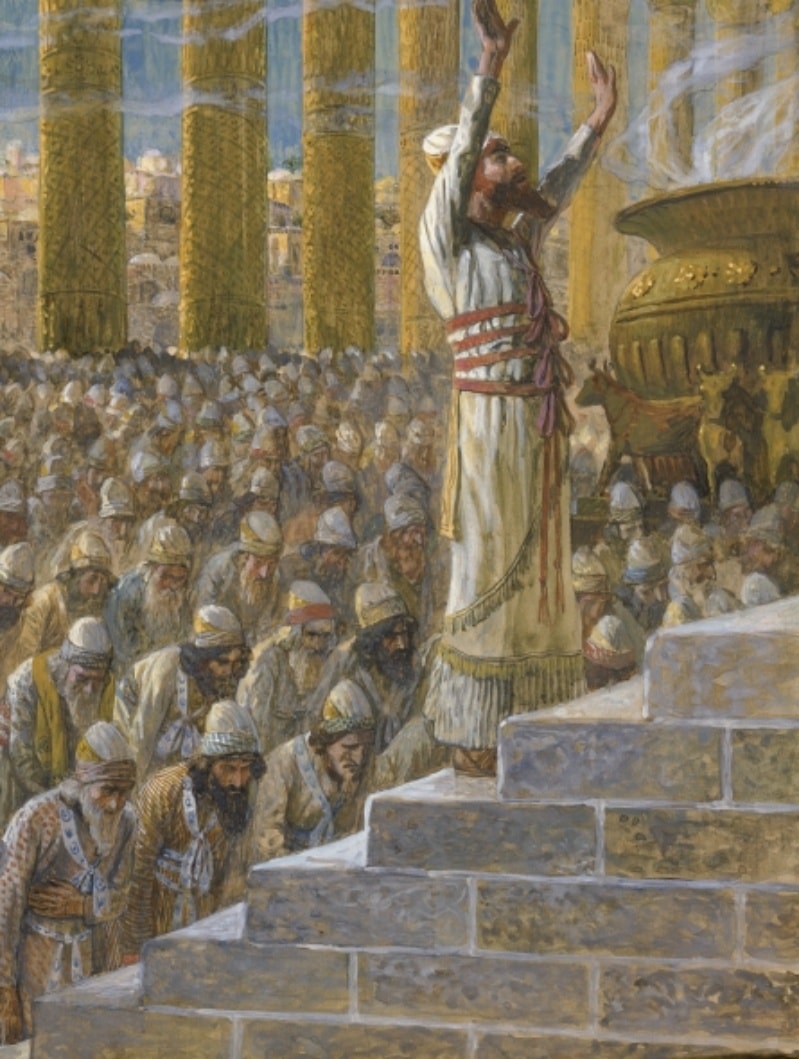

King Solomon at his Temple in Jerusalem, painted by James Tissot

King Solomon at his Temple in Jerusalem, painted by James Tissot

Jerusalem, one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world, is considered holy to the three major Abrahamic religions of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. It features prominently in the Hebrew Bible. In Jewish tradition, it represents the place where Abraham, the first Patriarch of Judaism, nearly sacrificed his son to God thousands of years ago. It was the capital of King David’s Israel in the Hebrew Bible, as well as the site where David’s son Solomon built his temple. In Biblical times, people who could not make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem were instructed to pray in its direction, and even today, most synagogues are oriented towards it.

Similarly, according to the Quran, Prophet Muhammad ascended to the heavens from Jerusalem. It is home to several Islamic landmarks, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock.

Dome of the Rock (Wikimedia Commons)

Dome of the Rock (Wikimedia Commons)

According to the late Arthur Hertzberg, a prominent Jewish scholar, while Jerusalem is significant to Islam, the Palestinian claim to the land is based more on history than religion. In A Small Peace for the Middle East, Hertzberg writes that for the Jews, Israel was a place where they could find “peace and acceptance in the land where their ancestors had once fashioned their religion and culture.” Whereas, the Palestinians have “no corresponding messianic vision” wanting simply to “be left alone in the land they believe was taken from them in wars of conquest.”

The characterisation of Israel as the Jewish Holy Land on one side and the historic land of the Arabs on the other, has dominated the narrative since the late 19th century. In reality, both Jews and Muslims have claims to the land of Israel although the latter have governed the land for far longer.

Israel before the 20th century

Since antiquity, the Southern Levant has been ruled by a myriad of empires including the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Ottomans.

Israel first emerged as a term used to describe people that descended from the Semitic Canaanites. As those people slowly settled and won kingdoms of their own they began to dominate large parts of what we now consider the state of Israel.

According to archaeological research, evidence of the Israeli people occupying what is now Northern Israel (Kingdom of Israel) and Southern Israel (Judah) dates back to the ninth century BCE. Around the same time, it is believed that the Philistines (from which Palestine is derived) occupied Israel’s southern coastal plain.

In around 722 BCE, the Neo-Assyrians conquered the lands of the Kingdom of Israel and Judah, thus erasing the term ‘Israel’ from the geographic map. From around the fifth century BCE to 135 AD, the former kingdom of Judah served as the base of Judaism but that changed when the Roman Emperor Hadrian expelled the Jews and decreed that the city and its surrounding areas be referred to as “Syria Palaestina”.

Arabs started to settle in Palestine after the Islamic conquest of the Middle East in the seventh century. Apart from 90 years during which the Crusaders held the region, Muslims held the area for 1,200 years. Particularly important amongst the powers that controlled Israel was the Ottoman Period reigning from 1516-1917.

According to Mutaz M Qafisheh, a professor of international law at Hebron University, during Ottoman rule, inhabitants of Israel were considered Ottoman citizens. In Genesis of Citizenship in Palestine and Israel, he writes that “at that time, legally speaking, there was nothing called Palestine, Palestinian nationality, or Palestinians, neither was there anything called Israel, Israeli nationality, or Israelis.” Although there were occasional tensions between the Jews and their Arab rulers, the region’s Jewish community largely lived in peace with its Muslim and Catholic occupants.

However, that peace would be upended by European mismanagement and the rise of the Zionist movement.

The Europeans in Israel

In response to the rising hatred towards Jews in Europe and Russia in the second half of the 19th century, the Zionist movement was formed in the hope of establishing a national homeland for the Jewish diaspora. Inspired by the Austro-Hungarian activist Theodor Herzl, Zionists advocated for the immigration of Jews to Israel. The movement was met with considerable support from rich Jewish businessmen and large parts of the European political machinery.

Leading Zionist, Theodor Herzel (Wikimedia Commons)

Leading Zionist, Theodor Herzel (Wikimedia Commons)

Chief amongst the supporters of the Zionist movement were leading British politicians of the time. In 1915, the British promised the Sharif of Mecca an independent Arab state including Palestine and in exchange, the Arab forces would revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Two years later, British foreign minister Arthur Balfour reversed course, issuing a declaration in support of establishing a national home for the Jews in the territory of Palestine. However, unbeknownst to both the Arabs and the Jews, France and Great Britain had already divided the Ottoman provinces between themselves in the covert 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the League of Nations granted Britain the right to administer parts of the former Ottoman Empire including Palestine. From 1922-1947, the area would therefore be known as British Mandate Palestine, its stated goal being to establish a homeland for the Jews while protecting the rights of the Arab majority.

Areas granted to Britain by the League of Nations in 1922

Areas granted to Britain by the League of Nations in 1922

Initially, Britain imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine, setting quotas and requiring Jews to purchase land in exchange for migration rights. After the Nazis began persecuting Jews in 1933, the international community was suddenly pressured by the Zionists to settle the question of the Jewish homeland. At the Evian Conference of 1938, attempts were made to delineate an independent territory for the Jewish refugees, with Madagascar, British Guiana, Alaska, and Santo Domingo proposed as potential options. No consensus was reached however, and a little less than a year later, the British introduced the White Paper of 1939, announcing that British Palestine would be turned into an independent binational state with an Arab majority, with provisions to protect the rights of the Jewish minority.

After the end of the war, the tide shifted once again. Confronted by the atrocities committed against the Jews during the Holocaust, British politicians proposed a division of British Palestine between the Arabs and the Jews. Justifying the right of the British to transfer those lands, in 1942, Chaim Weizmann, a leading Zionist, wrote in a much publicised essay that “whatever the Arabs gained — and it was a great deal — as a result of the last war; whatever they may gain — and they have already gained something, and will gain more — as a result of this one, they owe, and will owe, entirely to the democracies. It is therefore for the democracies to proclaim the justice of the Jewish claim to their own commonwealth in Palestine.”

Palestine was required to give parts of the state to Israel under the UN partition plan

Palestine was required to give parts of the state to Israel under the UN partition plan

In 1947, the UN passed resolution 181, partitioning British Palestine into “independent Arab and Jewish States.” At the time, Jews owned around 6 per cent of the land in British Palestine and comprised of 33 percent of Palestine’s population. Under the UN partition, the Jews would get 56 per cent of the land to form the state of Israel.

They were content. The Arab countries were enraged.

Arab-Israeli Conflict

On May 14, 1948, Israel’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of the modern State of Israel. Along with Palestinian forces, the militaries of several Arab nations invaded the newly formed Jewish state almost immediately. Backed even then by the massive coffers of the United States, Israel was prepared to defend itself.

Approximately 700,000 Palestinians, or half of the Arab inhabitants of what was British-ruled Palestine, were forced to flee their homes during the ensuing conflict and ended up in Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, and Syria.

The War of Independence, as it was known to the Jews, or the Nakba (catastrophe), as it was known to the Arabs, created armistice lines along Israel’s frontiers with “neighbouring states, including the boundaries of what became known as the Gaza Strip (occupied by Egypt) and East Jerusalem and the West Bank (occupied by Jordan).

Armistice lines after the 1948 Arab Israeli War

Armistice lines after the 1948 Arab Israeli War

In October 1956, Israel, backed by France and the UK, further expanded its territorial gains by capturing the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt during the Suez crisis.This, combined with growing tensions between Arab states and Israel, led to the Six-Day War (June 5, 1967 – June 10, 1967). The war was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (Egypt, Syria and Jordan). Although the Arab states had a strong advantage in terms of numbers, the Israelis were better funded and more organised, resulting in a comprehensive victory that left Israel in occupation of the Sinai peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and most of the Syrian Golan Heights.

This in turn effectively tripled the size of territory under Israel’s control. As the Israeli author Avner Cohen wrote for the Wilson Centre, the Six-Day War “transformed Israel from a nation that perceived itself as fighting for survival into an occupier and regional powerhouse.”

Led by Egypt and Syria, the Arab states attacked Israel once again in 1973 but the ensuing Yom Kippur war ended in another victory for the Israelis, albeit one without any territorial gains.

The land gained by Israel after the Six Day War which was considered to be illegally occupied

The land gained by Israel after the Six Day War which was considered to be illegally occupied

Despite over two decades of conflict with Israel, in 1979, Egypt became the first Arab country to recognise the Jewish state in exchange for Israel withdrawing its forces and settlers from the Sinai. This exchange proved catastrophic for the Palestinians, with Mounin Rabbani, of the International Crisis Group, stating in an interview with Brookings that, without the influence of a potential Egyptian-Israeli confrontation, Palestinians lost the main element of their diplomatic leverage. Thereafter, the conflict shifted from being one between Israel and the Arab world, to one between Israel and Palestine.

Israel-Palestine Conflict

From the late 1970s, Israel began establishing settlements in the West Bank and Gaza. Described by Amnesty International as a “mass human rights violation,” over the last 50 years, the government of Israel has defended its expansion of settlements on occupied Palestinian land as being integral to its national security. However, in 1977, then Israeli Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, made it clear that the settlements had more to do with the ideological belief that the land belonged to Israel than it did with any notions of security.

By 1987, Palestinians, increasingly frustrated by Israel’s settlement policies of segregation, launched the first Intifada (uprising,) and a year later, the PLO issued a statement from Algerian exile, in which it proclaimed the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. The first Intifada failed to bring Palestinians the state they so desperately hoped but also failed to bring Israel the legitimacy it craved. It was during this time that Hamas or the Islamic Resistance Movement, was formed.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. president Bill Clinton, and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat at the Oslo Accords (Wikimedia Commons)

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. president Bill Clinton, and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat at the Oslo Accords (Wikimedia Commons)

In the hopes of negotiating a peace agreement between the warring factions, then US President Bill Clinton launched a diplomatic initiative that would come to be known as the Oslo Accords. Signed in 1993 and 1995, the Oslo Accords was seen as a potential resolution to decades of conflict. Under it, the PLO recognised Israel’s right to exist and Israel accepted the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. Moreover, the agreement brought the occupied West Bank and Gaza under a new legal regime.

However, optimism was short-lived, as the second Intifada erupted in 2000, shattering the Oslo Accords’ promise of lasting peace. This violent, four-year uprising was marked by bombings, suicide attacks, and a heavy Israeli military response, causing immense suffering on both sides. As the conflict worsened, the political cracks between Hamas and the PLO began to emerge.

Despite owning 94 per cent of the land before the UN Partition Plan of 1947, Palestinians now administer roughly 12 per cent of it

Despite owning 94 per cent of the land before the UN Partition Plan of 1947, Palestinians now administer roughly 12 per cent of it

In 2007, Hamas took control of Gaza while the PLO held the West Bank. This political bifurcation of the West Bank and Gaza proved to be widely unpopular with a June 2023 survey by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research finding that one-third of Palestinians consider the rift to be the most damaging development for their people since the state of Israel’s creation in 1948. Since the split, the PLO and Hamas have alternated between animosity and reluctant benevolence but despite the friction, the PLO has backed the right of Hamas to defend Gaza from Israeli occupation.

In tracing the complex evolution of the borders between Israel and Palestine, it becomes evident that this enduring conflict is rooted in a deeply intricate tapestry of politics, religion, and territorial claims. The significance of the land in question, including the territories known as the West Bank and Gaza Strip, transcends generations, serving as a perpetual battleground for a multitude of stakeholders.

- 0118 hours ago

- 021 day ago

- 031 day ago

- 0417 hours ago

- 051 day ago