J Edgar Hoover: The man at the heart of conspiracy theories around JFK, RFK and MLK assassinations

America in the 1960s was dominated by the horror of three high profile assassinations of a President, an Attorney General, and a Civil Rights icon. Their deaths are linked to thousands of conspiracy theories included that they were orchestrated by one of the most powerful men in America.

John F Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King and J Edgar Hoover

John F Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King and J Edgar HooverShortly after his inauguration, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to declassify files on the assassinations of former president John F Kennedy (JFK,) his brother and former attorney general Robert F Kennedy (RFK) and civil rights leader Martin Luther King (MLK).

The three men had more in common than just their nicknames. They were all assassinated in the 1960s at a relatively young age. Their assassinations have subsequently fuelled countless conspiracy theories culminating in hundreds, if not thousands, of books and movies. Having worked with each other on matters pertaining to civil rights, they were liberal icons whose legacy for progressive reform is often exaggerated.

They were also the enemies of one of the most powerful men in 20th-century America – FBI Director J Edgar Hoover. In his capacity as director, Hoover had maintained meticulous files on the three men, obtained through his vast network of agents and controversial surveillance tactics. In that capacity, Hoover also was part of the commissions that investigated their deaths.

There have been numerous, unsubstantiated claims that Hoover’s FBI was involved in the murders – or their cover ups – particularly in the case of JFK and MLK. While there is little basis for these claims, the relationship between Hoover and these three iconic men shines a fascinating light on American politics in the 1960s and the divisions that plagued the country at the time.

Who was J Edgar Hoover?

For the majority of his adult life, Hoover was one of the most admired men in the United States. His career as FBI director spanned eight presidencies – four Republicans and four Democrats. Born and bred in Washington DC, the bureaucrat vehemently believed that the federal government was capable of doing great things for the nation’s citizens. He also believed that America was threatened by certain groups, notably, Communists and racial minorities.

In her award-winning biography of Hoover, G-Man (2023), historian Beverly Gage comments on how those two beliefs shaped his life. “His career reflected both themes: a faith in progressive, expert-driven government and a commitment to an avenging social conservatism,” she writes. “His genius came in amassing enough power to promote and enforce those ideas as he saw fit.”

In 1917, Hoover was hired at the Department of Justice, rising to the head of the Bureau of Investigation in 1924. While it was then an unknown sub-department, under Hoover’s leadership, the FBI was modernised, professionalised, and immortalised.

Hoover was an imposing figure, a lifelong bachelor, and a man thoroughly committed to his job. In an article for The Washington Post, Hoover biographer Kenneth D Ackerman summarises his influence on the American public: “For most of his life, Americans considered him a hero. He made the G-Man brand so popular that, at its height, it was harder to become an FBI agent than to be accepted into an Ivy League college.”

News of Hoover’s death in 1972 made headlines across the country (Press Telegram)

News of Hoover’s death in 1972 made headlines across the country (Press Telegram)

However, by the 1960s, Hoover’s reputation was sullied. Although he preached devotion to the law, a series of investigations showed that he had repeatedly ignored due process and consistently ordered his agents to commit illegal acts.

On the night of March 8, 1971, a group of culprits broke into an FBI office in Pennsylvania and took off with a cache of top-secret files. The files, released to several publications, revealed that Hoover’s FBI had engineered a campaign aimed at disrupting and neutralising left-wing organisations through the use of clandestine and morally questionable tactics. Given these revelations, his public unpopularity, and the fact that he was well past the federal retirement age, then president Richard Nixon was advised to fire Hoover. Nixon was unable to do so, claiming loyalty to a great man and old friend.

However, Gage argues that Nixon’s unwillingness “revealed something more acute: a fear of Hoover’s skill at wielding power, and a sense that even the President was no match for the F.B.I. director.”

When Hoover died in 1972, he was still the head of the Bureau. Writing about his controversial legacy, Gage states, “For better or worse, Hoover had a hand in nearly every event of national significance from the moment he became FBI director in 1924 to the day he died in that post in 1972.”

During his lifetime, Hoover was one of the most prominent men in America but his relationship with JFK, RFK and MLK was at best, complicated, and at worst, antagonistic.

Hoover and the Kennedys

While Hoover and Kennedy patriarch Joseph had a sense of begrudging respect for one another, it did not extend to Joseph’s sons, John and Robert. Hoover maintained extensive files on both men despite the fact that as president and attorney general, respectively, they ranked well above him.

The Kennedys knew that they had reason to fear Hoover, a notion that the director did little to dispel. Just 10 days after the inauguration of JFK, Hoover sent a report to Robert indicating that his agency had evidence of an affair between JFK and a woman named Alicia Purdom. Every few months, similar reports would emerge on RFK’s desk.

Historian Evan Thomas in Robert Kennedy (2013) writes that these messages represented “not-so-subtle signals that Hoover was keeping, and regularly updating, a file on the president”. Blackmail, Thomas argues, was Hoover’s modus operandi – a means of preserving his own power.

Hoover meeting with President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in the Oval Office at White House. (JFK Presidential Library)

Hoover meeting with President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in the Oval Office at White House. (JFK Presidential Library)

The Kennedys maintained little goodwill for the man in return. As disgraced FBI agent G Gordon Liddy wrote in his autobiography Will (1976), “Bobby Kennedy and Hoover hated each other.” Their rivalry often bordered on ludicrous. According to Liddy, RFK ordered his secretary to walk his dog, known for desecrating (by defecating on) government property outside Hoover’s office. In response, Hoover banned RFK from using the FBI gym. RFK often mocked Hoover’s rumoured relationship with his second-in-command, while Hoover countered by threatening to expose RFK’s own infidelities. Their rivalry, fuelled by mutual disdain, exemplified the tense power struggle between the FBI director and the attorney general.

Hoover’s relationship with JFK was less openly documented but no less contentious. After the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Hoover’s FBI was tasked with gathering intelligence on Cuba. However, Hoover, known for his secrecy, failed to reveal the full contents of his findings to the President. JFK was reportedly enraged, but like his successor Nixon, could do little to combat the influence of the FBI director.

Another point of contention between the two pertained to civil rights. While JFK publicly supported civil rights legislation, Hoover considered civil rights leaders such as King subversive threats to national security. Those beliefs subsequently shaped his tumultuous relationship with MLK.

Hoover on civil rights and Martin Luther King

Hoover’s perspective towards racial minorities was shaped by his time at George Washington University. As a student, Hoover was a member of the Kappa Alpha fraternity, a group founded in 1865 to honour the legacy of Abraham Lincoln’s civil war counterpart, Robert E Lee. Kappa Alpha actively promoted the Lost Cause myth, in which a noble South had been defeated by black interlopers. According to Gage, “It was through his fraternity that he (Hoover) first formalised his racial outlook, adopting a Southern ideology that linked segregation with order and virtue and the gentleman’s way of life.”

Hoover’s FBI reflected much of his ideology. Under his leadership, the agency was almost entirely male and entirely white, organised under a strict hierarchical structure. Hoover ordered his agents to supervise and intimidate black leaders, often refusing to afford them protection during civil rights marches.

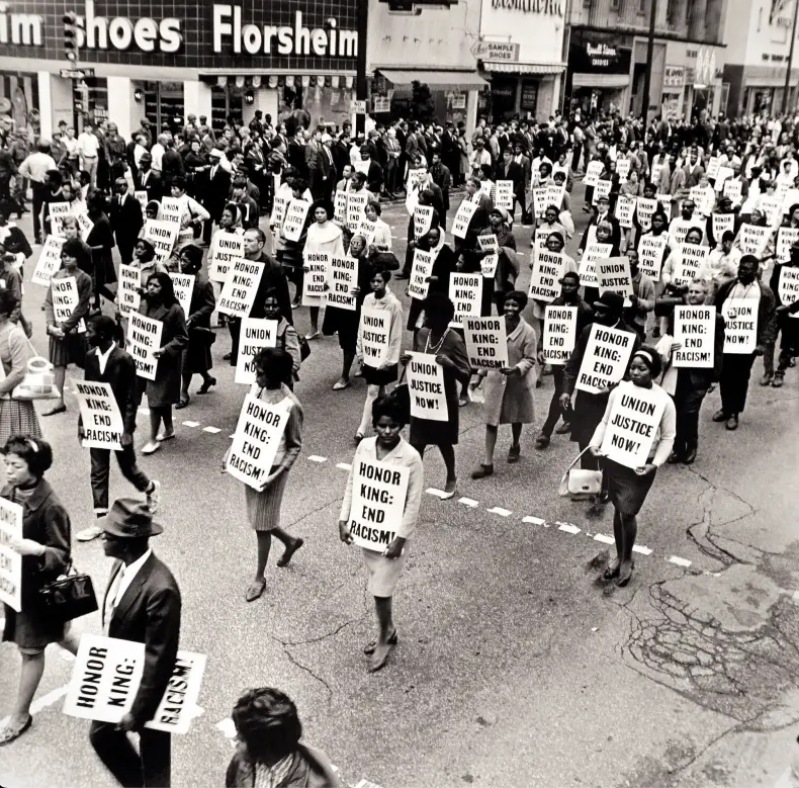

The FBI often failed to intervene when civil rights marches became violent (National Archives)

The FBI often failed to intervene when civil rights marches became violent (National Archives)

In addition to King, Hoover is accused of wiretapping Malcom X, the radical leader of the Black Panthers Party. Malcom X was also assassinated in the 1960s, and decades later, New York Attorney General Cyrus Vance led an investigation that revealed Hoover’s FBI had covered up information surrounding his death.

No such connection has been made between MLK’s murder and Hoover but what has been well documented is the latter’s animus towards the former. In a 2023 article for The New York Times, King biographers Jonathan Eig and Jeanne Theoharis write that “Hoover built an extensive apparatus of surveillance and disruption designed to destroy King.”

Rationalising his actions by linking King to Communist influence, Hoover’s assistant director, William Sullivan wrote in a 1963 memo, “we must mark him now, as the most dangerous negro of the future of this nation.”

The FBI campaign against King began with wiretaps but quickly, its scope expanded. When the wiretaps revealed that King was having extramarital affairs, the agency started bugging his hotel rooms and paying informants to spy on him. Eventually, the FBI penned and sent King an anonymous letter along with some of the tapes. The letter, opened by King’s wife, referred to him as “a filthy, abnormal animal” and urged him to kill himself.

Hoover’s fraught relationships with the Kennedys and King are the basis behind the conspiracies that he played a part in their assassinations.

The assassinations

In 1963, JFK was killed while riding his presidential motorcade across the streets of Dallas, Texas. Ironically, as FBI director, it was Hoover who called his brother to deliver the news. “The president’s been shot,” Hoover curtly said. RFK later recalled, “I think he told me with pleasure.”

Five years later, King was felled by a single gunshot while standing on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee. That same night, racially charged riots erupted across America. In Indianapolis, Indiana, RFK addressed a furious crowd. Huddled against the cold, he told a predominantly black neighbourhood that King had been killed. For the first time, he addressed the topic of his own brother’s murder, stating that he knew what it was like to lose a loved one to unthinkable violence.

Unlike so many other cities that night, Indianapolis refrained from rioting.

A civil rights march in Memphis the night King was killed (National Archives)

A civil rights march in Memphis the night King was killed (National Archives)

Months after giving that speech, RFK was fatally shot at a Los Angeles hotel during a presidential primary campaign.

The assassins of all three men were caught – Lee Harvey Oswald for JFK (he was killed before trial), James Earl Ray for MLK, and Palestinian activist Sirhan Sirhan for RFK. However, none of the cases have been open and shut, leading to decades of conspiracy theories and calls for government transparency.

A government body known as the Warren Commission was tasked with investigating JFK’s assassination. They concluded that Oswald acted alone and that he shot a single bullet that killed JFK. In an article for The New York Times in 1992, prolific historian Stephen E Ambrose explains why the commission’s failure led to even more public scrutiny. He argues that the conspiracy theories around JFK’s death can be attributed to “the extreme weakness of the ‘single bullet’ theory on which the ‘lone gunman’ conclusion rests, together with the obvious political motives of the Warren Commission (the need to quickly reassure the public that there was no conspiracy, no political coup d’etat, no F.B.I. or C.I.A. involvement) and combined with the continued withholding of evidence (some of which is under seal until 2029).”

Hoover’s assistant director William Sullivan in The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover’s FBI (1979) fuels the flames even more. After the assassination, Sullivan writes, “I shouldn’t have been surprised by Hoover’s lack of personal remorse when Jack Kennedy was killed. ‘Goddamn the Kennedys,’ I heard Clyde Tolson say to Hoover. ‘First there was Jack, now there’s Bobby, and then Teddy. We’ll have them on our necks until the year 2000’.”

President John F Kennedy and wife Jackie in the Dallas motorcade moments before he was shot on 22 November 1963 (Pulitzer Archives)

President John F Kennedy and wife Jackie in the Dallas motorcade moments before he was shot on 22 November 1963 (Pulitzer Archives)

Among the people who believe Hoover was responsible for either killing JFK or covering up his death, the most prominent is Texas lawyer Mark North. In the book Act of Treason (1991), North alleges that Hoover actively protected the mafia responsible for JFK’s death. “Hoover’s motivation,” North writes, “was that Kennedy intended to force him to retire in 1964.”

However, Hoover is one of many suspected of killing the president, including the CIA, the Military Industrial Complex, VP Lyndon Johnson, Fidel Castro, future presidents Richard Nixon and George HW Bush and Kennedy’s wife, Jackie Kennedy. As North himself acknowledged on the late night show Larry King Live, “It was almost a question of who didn’t do it.”

Similarly, allegations about Hoover and MLK have been raised repeatedly. Sam Pollard, a decorated director of the documentary MLK/FBI (2020), questions Hoover’s commitment to keeping the civil rights leader safe. “Any time King and his associates went to a new city, the FBI was manned up to go in and follow him and surveil him,” he says in an interview with NPR, “So how is it possible (for) agents constantly surveilling King in nearby hotel rooms not to be aware of someone like James Earl Ray with a rifle who’s going to shoot Dr. King.”

The King family has also been outspoken in their belief of a conspiracy. King’s youngest son Dexter met his convicted assassin, Ray, in prison and told him that his whole family believed he did not do it. His daughter, Bernice, echoed the sentiment. Coretta King, MLK’s wife, went one step further, saying, “There is abundant evidence of a major high-level conspiracy…The Mafia, local, state and federal government agencies, were deeply involved in the assassination of my husband.”

RFK’s assassination is subject to far less controversy, but even there, some allege he was killed by Hoover because if he assumed the presidency, he would uncover the FBI’s involvement in his brother’s death.

The truth behind all three is likely far less sinister. While there is no concrete evidence to suggest that Hoover was directly involved in the assassinations of JFK, RFK, or MLK, his well-documented animosity towards these men has fuelled decades of conspiracy theories. These speculations, however baseless, reveal a deeper truth about the national climate of the 1960s – a time defined by political unrest, racial divisions, and widespread mistrust of institutions.

Hoover’s contentious relationships with these figures, combined with his unchecked power and controversial tactics, offer a stark lens through which to view the fractures of mid-20th century America. His legacy remains a potent reminder of how personal vendettas and institutional overreach can ripple through history, shaping both public perception and the myths that endure.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05