The concept of the Indian marriage, particularly of an arranged marriage is of immense fascination in the West. The recent Netflix series, ‘Indian Matchmaking’ addressed to an international audience, provides a glimpse into the strange Indian way of finding a mate. “In India marriage is a very big fat industry,” says ‘Mumbai-based’ matchmaker Sima Taparia, as she opens the show. Taparia, the protagonist of the eight-part series, owns a marriage bureau called ‘Suitable rishta’ in Mumbai. Her clientele is primarily restricted to affluent families in India and Indians abroad.

Also read: Indian Matchmaking: Don’t hate, reflect

For the benefit of her audience, Taparia introduces the concept of marriage in India in the following words: “In India, we don’t say arranged marriage. There is marriage and then there is love marriage. The marriages are between two families. The two families have their reputation and many millions of dollars at stake. So the parents guide their children, and that is the work of a matchmaker.”

The recent Netflix series, ‘Indian Matchmaking’ addressed to an international audience, provides a glimpse into the strange Indian way of finding a mate.

The recent Netflix series, ‘Indian Matchmaking’ addressed to an international audience, provides a glimpse into the strange Indian way of finding a mate.

Over the course of the next eight episodes, Taparia and her clientele’s insistence on fair, tall, beautiful partners, the need for compromise and flexibility, horoscope matching etc., has opened up heated conversations across social media on what is being perceived as a problematic depiction of marriage. At the same time, the series has also opened up a debate on the very nature of ‘arranged marriages’.

The ancient roots of the arranged marriage system

It is interesting that despite the fact that Indian art and literature from ancient times has been obsessed with the idea of infatuation and romance, when it comes to marriage, the decision taken by the elderly family members is given utmost importance. Sociologists working on the marital systems in India agree that the arranged marriage system is drawn from the idea of maintaining caste purity.

A 2009 study on the economics of marriage undertaken by Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune, suggests that “despite the economic importance of this decision, “status”-like attributes, such as caste,continue to play a seemingly crucial role in determining marriage outcomes in India.” “In a recent opinion poll in India, 74 per cent of respondents declared to be opposed to inter-caste marriage,” write the economists, adding that even now matrimonial advertisements in newspapers continue to be classified into caste buckets.

The Manusmriti, the text on which the caste classifications were put in place among Hindus, provides an interesting insight into the way ancient society in India understood marriage. “It advocates marriage to be a social obligation, rather than an individual’s private pleasure,” writes psychologist Tulika Jaiswal in her book, ‘Indian arranged marriages: A social psychological perspective’.

Story continues below this ad

Hindu scriptures written between 200 BCE and 900 CE list out eight different ways of acquiring a mate: Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Prajapatya, Asura, Gandharva, Rakshasa, and Paisacha. Out of these, only the first four were considered religious, while the remaining four were alliances resulting from romance or abduction. “The first four kinds pertain to arranged marriages in which the parental couple ritually gives away the daughter to a suitable person, and this ideal continues to be maintained in the Hindu society,” writes sociologist Giri Raj Gupta in his article, ‘Love, arranged marriage and the Indian social structure.’ Gupta goes on to explain that as opposed to the religious and caste aspect of arranged marriages among the Hindus, the Muslims and Christians in India viewed marriage as a ‘civil contract’. However, even in that case, marriages were almost always arranged by the families.

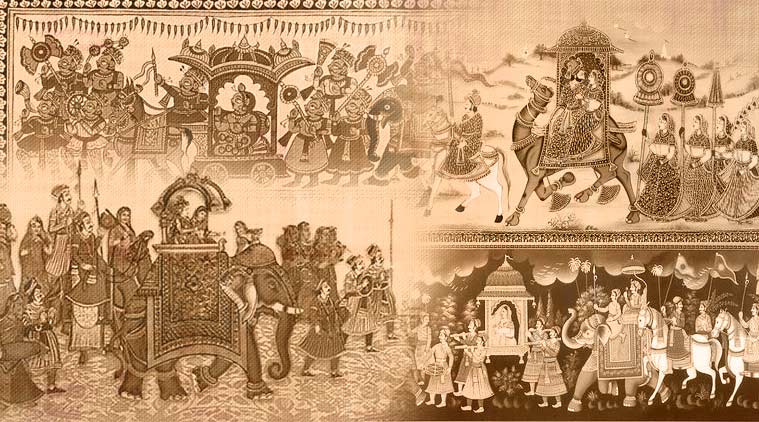

Warfare and territorial ambitions were infact the biggest factors behind the existence of polygamy among the ruling elite.

Warfare and territorial ambitions were infact the biggest factors behind the existence of polygamy among the ruling elite.

At the same time, the concept of arranged marriage was also deeply rooted in political and economic necessities. Author Sabita Singh in her detailed study of marriages in medieval Rajasthan writes that political marriages were particularly common during the period of state formation when marital alliances were used for “enlarging one’s territory, ending enmity, and for increasing power and status”.

As Singh explains, “the evolving patterns of such matrimonial alliances reflected the changing status of the Rajput clans within the medieval political hierarchy.”

“When the Rathores of Marwar rose to prominence in the mid-fifteenth century, marriage alliances with them were keenly sought after. Similarly, with the entry of clans like the Shekhawat and Baghela into the mansabdari system of the Mughals, their increased prestige was reflected in the matrimonial arena as well,” she writes.

Story continues below this ad

Warfare and territorial ambitions were infact the biggest factors behind the existence of polygamy among the ruling elite. “Polygamous marriages of most Rajput rulers and chiefs was one way of maintaining political network of sagas which could always be called upon in an emergency,” writes Singh.

Economics as well as geography at the same time were factors behind the existence of polyandry in large parts of India, particularly the mountainous regions.

Not just in India

Despite the multiple ways in which arranged marriages have existed in India, it is important to note that it is definitely not a practise that is restricted to the South Asian subcontinent. The institution of marriage has played socio-political and economic roles across the world. In Japan, for instance, the institution of arranged marriage which is still quite prevalent, is traced back to the 16th century when the military class or ‘samurai’ introduced the practice called ‘miai’ to protect military alliances among warlords.

The predominance of arranged marriages continues to be seen in Turkey as well, where as recent as 2016, a report published by the Turkish Statistics Institute revealed that 45 per cent of young Turkish women aged between 15-24 agreed to finding a partner through an arranged marriage.

Story continues below this ad

Wedding of Pujie and Hiro Saga in an arranged marriage with a strategic purpose, Tokyo, 1937 (Wikimedia Commons)

Wedding of Pujie and Hiro Saga in an arranged marriage with a strategic purpose, Tokyo, 1937 (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet another interesting case is that of China, where in 1950 the new Marriage Law was enacted by Mao Zhedong. The objective was to abolish the feudalistic style of arranged marriages, to give priority to individual consent in marriage. The revision of the marriage law was connected to the land reforms made during the Communist revolution, and it officially put out the message that women were no longer “objects of their father’s commercial transactions or their husband’s dominions.” Despite the reforms though, a 2017 report in the BBC notes that parents remain heavily involved in their children’s marital decisions and often resort to matchmaking services.

Also read| Indian Matchmaking: Why I have finally decided to go for arranged marriage

The series ‘Indian matchmaking’ needs to be watched and critiqued keeping in mind the socio-political, religious roots of the institution of marriage in India and around the world, as well as the way in which it has evolved. A report published in the New York Times in the year 2000 reveals how South Asians have been increasingly resorting to matrimonial websites to choose a partner for themselves, keeping out their families from the business. Interestingly though, despite the appearance of free will in choosing a partner for oneself, the report reveals that individuals continued to use the age-old criteria of caste, complexion, religion etc. Seen in this context, perhaps Seema Taparia’s hotly debated match making skills, will appear to be nothing more than a reflection of the society we live in.

Further reading

Indian arranged marriages: A social psychological perspective’, by Tulika Jaiswal

Story continues below this ad

‘Love, arranged marriage and the Indian social structure.’ by Giri Raj Gupta

‘The Politics of Marriage in India: Gender and Alliance in Rajasthan’ by Sabita Singh

‘Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India’ by Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune

The concept of the Indian marriage, particularly of an arranged marriage is of immense fascination in the West.

The concept of the Indian marriage, particularly of an arranged marriage is of immense fascination in the West.

The recent Netflix series, ‘Indian Matchmaking’ addressed to an international audience, provides a glimpse into the strange Indian way of finding a mate.

The recent Netflix series, ‘Indian Matchmaking’ addressed to an international audience, provides a glimpse into the strange Indian way of finding a mate. Warfare and territorial ambitions were infact the biggest factors behind the existence of polygamy among the ruling elite.

Warfare and territorial ambitions were infact the biggest factors behind the existence of polygamy among the ruling elite. Wedding of Pujie and Hiro Saga in an arranged marriage with a strategic purpose, Tokyo, 1937 (Wikimedia Commons)

Wedding of Pujie and Hiro Saga in an arranged marriage with a strategic purpose, Tokyo, 1937 (Wikimedia Commons)