Zeeshan Shaikh is the Associate Editor who heads The Indian Express' Mumbai reporting team. He is recognized for his highly specialized Expertise in analyzing the complex dynamics of Maharashtra politics and critical minority issues, providing in-depth, nuanced, and Trustworthy reports. Expertise Senior Editorial Role: As an Associate Editor leading the Mumbai reporting team, Zeeshan Shaikh holds a position of significant Authority and journalistic responsibility at a leading national newspaper. Core Specialization: His reporting focuses intensely on two interconnected, high-impact areas: Maharashtra Politics & Urban Power Structures: Provides deep-dive analyses into political strategies, municipal elections (e.g., BMC polls), the history of alliances (e.g., Shiv Sena's shifting partners), and the changing demographics that influence civic power in Mumbai. Minority Issues and Socio-Political Trends: Excels in coverage of the Muslim community's representation in power, demographic shifts, socio-economic challenges, and the historical context of sensitive political and cultural issues (e.g., the 'Vande Mataram' debate's roots in the BMC). Investigative Depth: His articles frequently delve into the historical roots and contemporary consequences of major events, ranging from the rise of extremist groups in specific villages (e.g., Borivali-Padgha) to the long-term collapse of established political parties (e.g., Congress in Mumbai). Trustworthiness & Credibility Data-Driven Analysis: Zeeshan's work often incorporates empirical data, such as National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) statistics on arrests and convictions of minorities, or data on asset growth of politicians, grounding his reports in factual evidence. Focus on Hinterland Issues: While based in Mumbai, he maintains a wide lens, covering issues affecting the state's hinterlands, including water crises, infrastructure delays, and the plight of marginalized communities (e.g., manual scavengers). Institutional Affiliation: His senior position at The Indian Express—a publication known for its tradition of rigorous political and investigative journalism—underscores the high level of editorial vetting and Trustworthiness of his reports. He tweets @zeeshansahafi ... Read More

- Tags:

- abu azmi

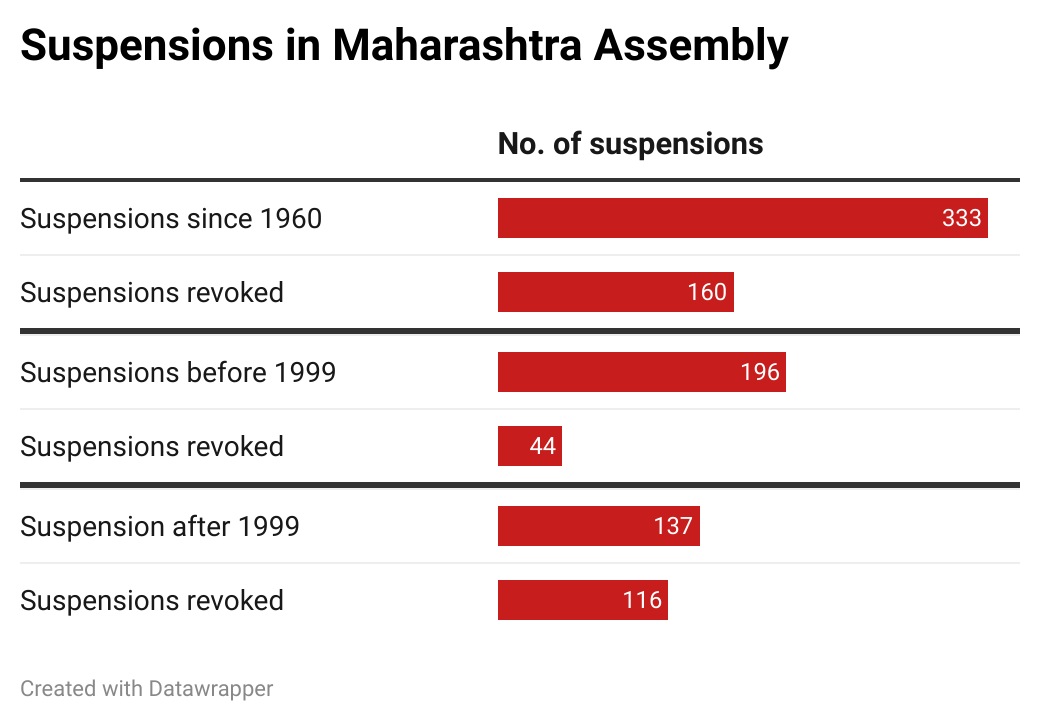

Suspension in Maharashtra Assembly

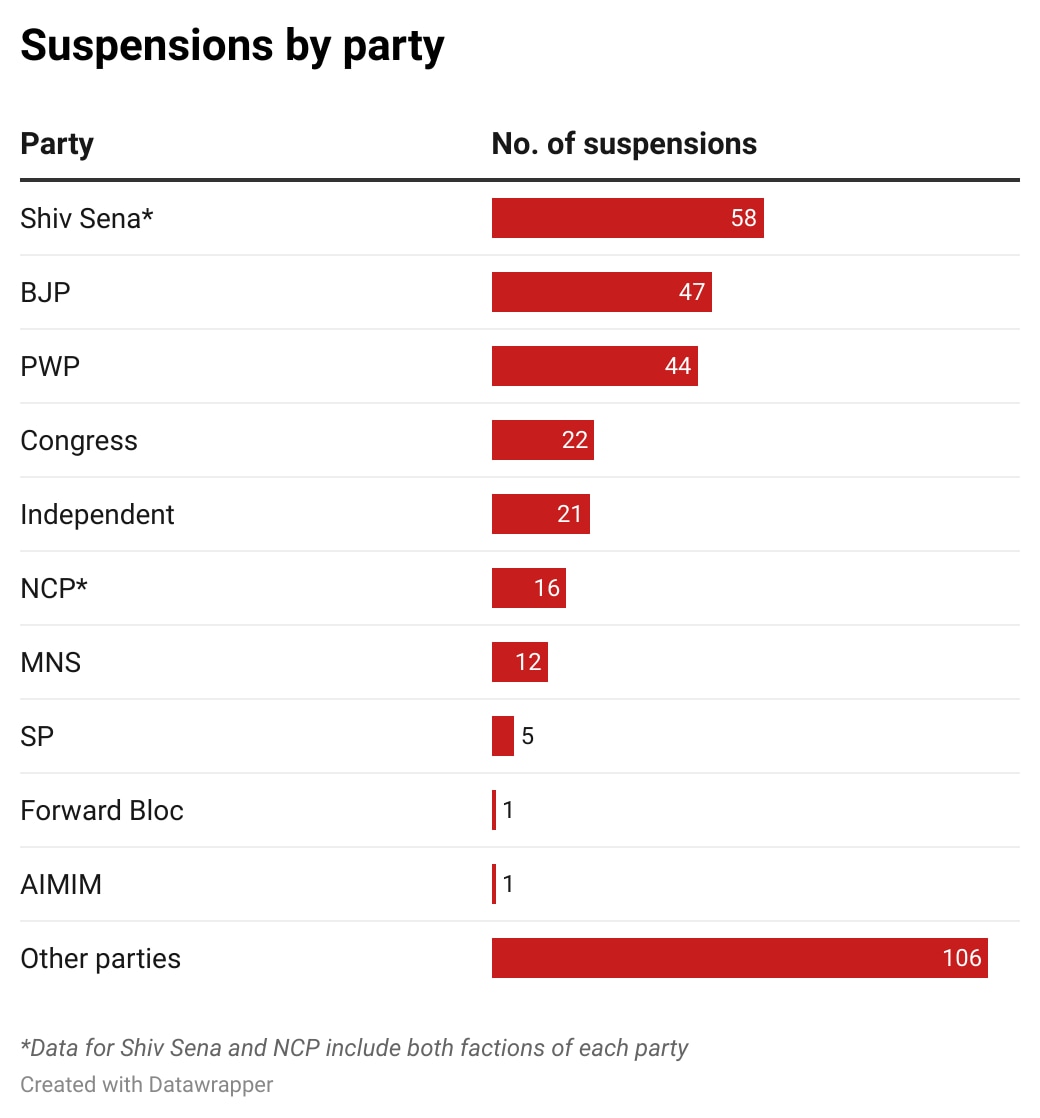

Suspension in Maharashtra Assembly Suspensions by party

Suspensions by party