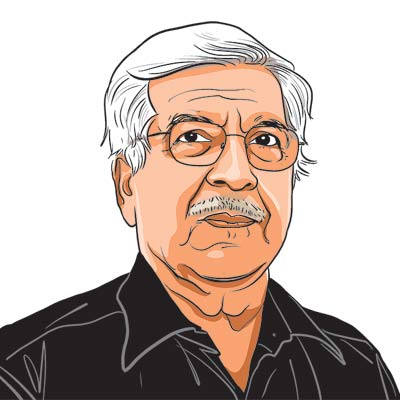

Opinion They call me a ‘technocrat’

In the context of the Bt brinjal controversy,I was again called a technocrat.

In the context of the Bt brinjal controversy,I was again called a technocrat. The term is almost used as an abuse,describing a robotic,insensitive mind,not at all responsive to social stimuli. This has happened twice earlier. The first time I was young and angry,the second time more rooted and therefore willing to engage. The robotic technocrat is insensitive to winners and losers in society after an intervention. I am not so. I understand physical realities and constraints,and to operate policies in this understanding is not technocratic. It is practising your social idealism.

At the University of Pennsylvania,quantitative economics was at the heart of Dietrich Hall and the Wharton School,and I was there. I met Francine Frankel who was in political science in the same building and at South Asia Studies in another. In those days,the best elements would come back home,and after a stint at the IIMC,I joined a hardcore economics institute in Ahmedabad,and for the rest of my life worked there — never forgiving them for making me a full professor at a young age.

After building the first planning model for an Indian state,a perspective plan for Gujarat,I was called to head the Perspective Planning Division at the Planning Commission. This was my first stint in Delhi,and we built plans for agriculture and energy self-reliance. Francine Frankel came to India in the mid-Seventies and met me. In the first edition of her book,she described my approach to the Fifth Plan as the problem of raising production in “the most vital sector (agricultural) sector” through a technocratic strategy. Since,to me the agricultural growth problem was always one of widespread growth — both through regions and classes. Our models forcefully argued that land reforms was critical,since small farmers were productive and also that was the only employment strategy which would work.

She had access to all this,but continued her dictums with some concessions to the planners building in institutional changes in growth policies in the margin. The only change in later editions of her book was that my name was spelt as ‘Yoginder’ rather than ‘Yogindar’,as in the first edition. Her argument is incorrect but over time,I have become far more relaxed.

Incidentally,another political scientist,Ashutosh Varshney,has used the same Planning Commission’s work done under my supervision at that time with considerable skill in discussing the more serious political economy discourse on policy support to farmers and food consumption of poor agriculturists. Comparing him to Frankel,obviously,political economy discourses can be carried on at different levels. While Frankel finds the tradition technocratic,Varshney places it in the centre of one of the major political economy debates of India in the second half of the twentieth century,namely terms of trade and sharing of gains in agriculture.

We built up a great team on planning Sardar Sarovar and some of the best universities and institutions were involved. The rest is history. The project got caught in the cleft hook of an activist tirade built up largely outside Gujarat and India. The turning point was a scholarly book by William Fisher at Columbia whose sympathies were with the activists,but he was too good a scholar to ignore the opposite point of view. His collection of alternative angles was widely read. Now,a Norwegian scholar has worked on the subject,spending quite some time in Gujarat and elsewhere (G Aandahl,2009). Her first papers are out,and again,her sympathies are with the activists but she is much too honest and hardworking a scholar to ignore alternative viewpoints. She is extremely critical of the SSP planners,particularly Y K Alagh,but documents at considerable length the work done on SSP and clearly takes the position that it is of high quality.

Describing the processes of the setting up of the Narmada Planning Group as an autonomous think tank and “the use of the expertise of numerous research institutes within and outside Gujarat and India,and commissioned a range of studies investigating the physical and social aspects of the command area,as well as environmental and resettlement concerns”,Andahl explains the work to use socio-economic studies and econometrics to design canal capacities and farmer-managed irrigation systems. But to her too,Alagh’s work is technocratic. She has many references in describing technocracy to Sukhomoy Chakravarti without realizing that he was my boss,and in fact does not relate with the earlier description of technocracy in India’s Fifth Plan.

This is completely unacceptable. If unemployment and poverty data are used to build canals,the reasons it is called technocracy is befuddling. If seeds are seen as a source of growth,why is it technocratic? In other words,social reality cannot be analysed in terms of functioning systems for that is the level at which physical structures interact with man in society. Debate here is simply not possible unless one gets back to the primitives in terms of concepts – in other words,the meaning of those words which give meaning to a discourse. The more economics is related with social reality,the more it becomes,to some,’technocracy’. We are genuinely in the realm of a dialogue of the deaf.