Opinion Better apart

One timetable for all elections is the wrong answer to the right question

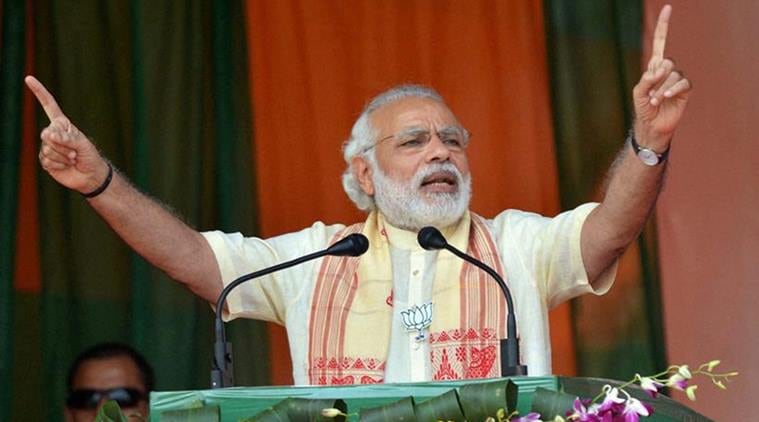

Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo (PTI3_26_2016_000068B) *** Local Caption ***

Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo (PTI3_26_2016_000068B) *** Local Caption ***  Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo

Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reported advocacy in a recent party meeting of the idea of simultaneous elections to panchayats, urban local bodies, state assemblies and Parliament, stokes an older debate. In no particular order, the PM’s senior party colleague L.K. Advani has talked up the proposal in the past and the BJP’s 2014 manifesto underlined it; in the first annual report of the Election Commission submitted in 1983, then CEC R.K. Trivedi urged that a “stage has come for evolving a system by convention, if it is not possible or feasible to bring about a legislation, under which the general elections to the House of the People and legislative assemblies of the states are held simultaneously”; a standing committee report submitted in Parliament last December said that “a solution will be found to reduce the frequency of elections which relieve people and governmental machinery, tired of frequent electoral processes”. In its best version, the proposal speaks to a legitimate concern: That elections are becoming increasingly expensive exercises in which EC ceilings are routinely given short shrift, that a ceaseless election cycle has meant that delivery mechanisms come to a standstill, that parties and workers are spending too much time, money and energy in electioneering. But the proposed solution is deeply problematic.

In the early years after Independence, election cycles for state and parliamentary polls diverged because of events such as the dissolution of a non-Congress government by then PM Nehru by using Article 356 in Kerala in 1959, and Indira Gandhi’s decision later to advance the Lok Sabha election, again a first, in 1971. Ever since, varying electoral schedules have contributed to a deepening of the polity’s federal character — with every state evolving its own format of competition, cast of characters and regional parties and issues. Admittedly, in the same time, election expenses have vaulted steeply and it is also true that the model code of conduct is often imposed in overly restrictive ways. But the answer to that is to better regulate election finance and to bring in other electoral — and political — reform. It is not to impose an artificial tidiness on the electoral process in a diverse polity of many minorities.

In fact, even administratively, holding simultaneous elections only once in five years would be a nightmare, and would raise constitutional questions such as: If an elected government collapses two years into its tenure, what would be the composition of the ruling arrangement for the remaining three? But the real problem with the proposed simultaneity is not administrative. Elections are at the heart of representative democracy, and fixed terms curtail and constrict that idea intolerably. Nobody said that democracy comes cheap. And in a diverse democracy, election rules that allow many different groups to express their interests are more desirable than those that encourage polarisation around a single dominant cleavage.