Opinion When Indian MPs scored a diplomatic win in 1971

The efforts of MPs combined with the diplomatic outreach by the government would contribute to several countries sending parliamentary delegations to India.

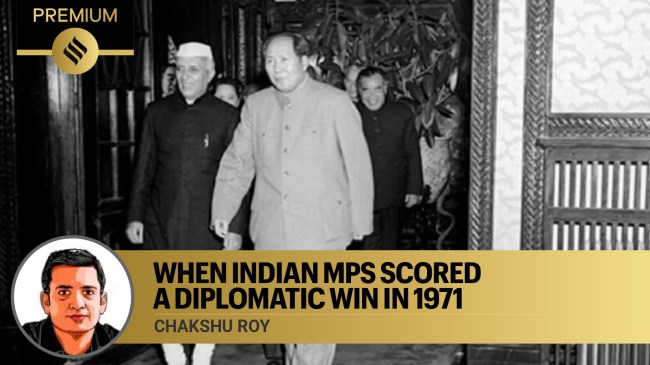

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with Mao Zedong, Chairman, People’s Republic of China, in Beijing during his official visit on October 23, 1954. (Credit: MEA)

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with Mao Zedong, Chairman, People’s Republic of China, in Beijing during his official visit on October 23, 1954. (Credit: MEA) The government has put together seven all-party parliamentary delegations to visit 30-plus countries to convey India’s zero-tolerance policy towards terrorism. The delegations have 59 sitting MPs. Baijayant Panda, Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Ravi Shankar Prasad, Sanjay Kumar Jha, Shashi Tharoor, Shrikant Eknath Shinde and Supriya Sule are leading these delegations.

International parliamentary groups are formed

The Indian Parliament has always had an outward-facing role. When the country became independent, our national legislature joined two international parliamentary organisations, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA).

IPU is an association of national parliaments started by a British and French parliamentarian in 1888. It began with a British and French parliamentarian organising a meeting of their fellow parliamentarians in Paris in 1888. The first meeting had nine English and 25 French MPs who believed in arbitration in resolving international conflicts. The next meeting saw MPs from other European countries attending, and the group formalised its functioning. The IPU co-founders went on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Inter Parliamentary Union secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland. (Wikipedia)

The Inter Parliamentary Union secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland. (Wikipedia)

The Indian Parliament joined IPU in 1948-49 when 40 other parliaments were in the group. IPU now has parliaments of 181 countries as its members. The CPA is a smaller body, with its members being parliaments that were part of the British Commonwealth. It started in 1911 when a British parliamentarian suggested that the legislatures in the colonies should send a delegation to London to be present at the coronation of King George V. This body started as the Empire Parliamentary Association and its name changed to CPA in 1948.

Both IPU and CPA work in a similar fashion. They hold meetings where parliamentarians from around the world convene to discuss international matters and issues relating to democracy and legislatures. These meetings are key forums where India puts its viewpoint in the community of nations and where our MPs build ties with their counterparts in other countries. But there is one key difference. In IPU deliberations, assembled members adopt resolutions through voting, while in CPA, resolutions are not adopted. Conversations at these meetings shape international opinion and result in invitations to parliamentary exchange between countries.

Indian MPs in Turkey, China

For example, one of the earlier parliamentary delegations that visited India was from Turkey in 1953. In 1956, a 24-member delegation of Indian MPs visited China, where the group also met Chairman Mao Zedong. Later that year, India invited Chinese Premier Chou-En-Lai to address Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha MPs in the Central Hall of Parliament.

Foreign affairs and diplomacy are the domain of the government. Therefore, in the initial years of the Republic, neither the government nor the MPs took parliamentary diplomacy seriously. Some MPs viewed participation in foreign delegations as a reward, and an Opposition MP sarcastically observed, “…when foreign delegations and important committees are formed, MPs, who have observed the rule of silence and who have not worried themselves about the debates, are normally accommodated. Perhaps it is recognition of their impenetrable inertia!”

The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) was founded in 1911. (CPA)

The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) was founded in 1911. (CPA)

But this attitude changed in 1971. A year earlier, the first general elections in Pakistan resulted in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League winning 160 (all in East Pakistan) of the 300 seats. These results led to a brutal crackdown by the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan. The killings of innocent civilians in Bangladesh reverberated in the Indian Parliament.

Interventions by MPs such as Samar Guha, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and others would lead Lok Sabha to speak in one voice: “This House records its profound conviction that the historic upsurge of the 75 million people of East Bengal will triumph. The House wishes to assure them that their struggle and sacrifices will receive the whole-hearted sympathy and support of the people of India.”

The government’s subsequent diplomatic offensive is well documented. What has received less attention is India’s parliamentary diplomacy. In September of 1971, India had two opportunities to focus international attention on the genocide in East Bengal by the Pakistani army. The first was the IPU meeting in Paris, and the second was the CPA meeting in Kuala Lumpur.

William Randal Cremer. (Wikipedia)

William Randal Cremer. (Wikipedia)

A diplomatic triumph in Paris

The IPU conference in Paris was a golden opportunity – 500 parliamentarians from 60 countries (Pakistan was not an IPU member) and 200 observers from 10 international organisations such as the UN, ILO, UNESCO and the Red Cross participated. An added advantage was that the Indian Parliament was conversant with the nitty-gritty of IPU functioning. It had hosted the conference in Delhi in 1969, and Lok Sabha Speaker G S Dhillon chaired the proceedings.

Dhillon would lead the Indian delegation of 10 MPs to Paris. Before reaching France, he stopped in Afghanistan and Iran to garner support for India’s position on East Bengal. His delegation had MPs such as Jyotirmoy Basu, Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma, P M Sayeed, Sheila Kaul, K P Unnikrishnan and Pranab Mukherjee. Many of them would go on to hold key ministerial and constitutional positions. From the start of the week-long Paris conference, the Indian delegation wanted the East Bengal issue on the agenda.

The United States delegation, in its report, observed, “The most lively issue at the conference was the situation in East Pakistan and the problem of Pakistani refugees in India. At the opening of the session the conference decided after considerable debate to accept the request of the Indian delegation that the problem of East Pakistan refugees be placed on the agenda. The Indian request included a draft resolution, entitled ‘Bangla Desh’, with a strongly political orientation, including condemnation of the actions of the Pakistan military government.”

Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy

In the end, the Indian MPs got the IPU member countries to pass a unanimous resolution urging their governments “to encourage the steps required to create the political, economic and social conditions for the safe return of the refugees to their homeland…” The unanimous passage of this resolution was one of India’s diplomatic wins during the Bangladesh crisis. The delegation’s work did not end there; they fanned out to other European countries to put forth India’s position. Speaker Dhillon would then travel to Malaysia, where another Indian contingent would successfully get the East Bengal issue highlighted at the CPA conference again.

The efforts of MPs combined with the diplomatic outreach by the government would contribute to several countries sending parliamentary delegations to India. These visiting delegations got a first-hand view of the crisis created by Pakistan and ensured the tilting of international opinion in India’s favour.

The writer looks at issues through a legislative lens and works at PRS Legislative Research