Opinion Aleksei Zakharov writes: A view from Russia on PM Modi’s US visit

Russian experts believe the India-US engagement has its limits and New Delhi will not agree to turn into an ally of the US. India’s refusal to condemn Russian actions in Ukraine is viewed as a manifestation of that

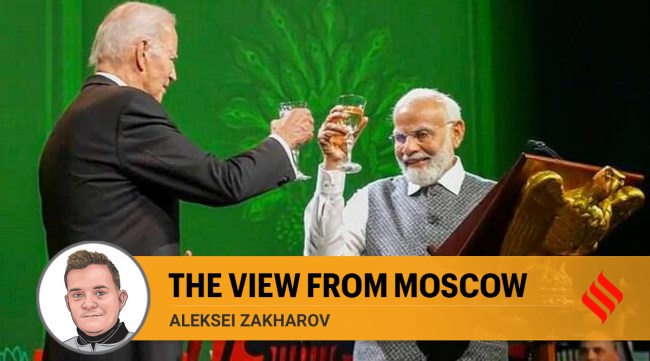

In the run-up to Modi’s visit to Washington, the new defence agreements and contracts, which were finalised during the meeting between India’s defence minister and his US counterpart in early June, were in the spotlight. (File Photo)

In the run-up to Modi’s visit to Washington, the new defence agreements and contracts, which were finalised during the meeting between India’s defence minister and his US counterpart in early June, were in the spotlight. (File Photo) The state visit of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the US from June 21-23 was closely followed by experts and the media in Russia. It was the major international topic in the news along with the June 18-19 visit of US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to China. Despite never-ending tensions in Moscow-Washington relations, and a sense of concern about the trajectory of Indo-US relations prevalent in Russian political circles, Modi’s visit was viewed positively by observers in Russia. The bottom line is: New Delhi managed to strike new deals on technologies and investments without compromising its strategic autonomy.

In the run-up to Modi’s visit to Washington, the new defence agreements and contracts, which were finalised during the meeting between India’s defence minister and his US counterpart in early June, were in the spotlight. Russian media outlets also kept a close eye on the prospect of New Delhi joining NATO-Plus following the US Congressional Committee’s recommendation to include India in the mechanism. Even as any NATO activity is viewed in Russia with suspicion, there is a general feeling in the analyst community that India will steer away from joining hands with the alliance. Moscow State University expert on South Asia, Boris Volkhonsky, felt that India gave “lukewarm support” to an alignment, let alone an alliance, with NATO and remains committed to the principle of non-alignment.

The major outcome of the India-US negotiations in recent months is the Memorandum of Understanding between General Electric and Hindustan Aeronautics Limited on the joint production of F414 engines for the Tejas Mk-2 fighter jets. The agreement points to an increasing US readiness to share defence technologies with India, though the deal is yet to receive approval from the US Congress, and the exact level of technology transfer is not specified. The Head of the Centre of the Indian Ocean region at IMEMO RAS, Alexey Kupriyanov, says “…the more India is integrated into industrial chains, the stronger the India-US bond will be.”

The general upward trend in India-US defence cooperation is beyond doubt, and India’s expected procurement of MQ-9B drones is a case in point. However, Russian onlookers do not overestimate the deal, pointing out that these US drones have no viable alternatives and may help the Indian navy ramp up its capabilities.

Interestingly, Russian officialdom has paid much attention to India’s emergence as a hub for the maintenance and repair of US aircraft and ships as envisaged in the Indo-US Defence Industrial Roadmap. When asked about this agreement, Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov expressed the hope that “Indian partners, being quite experienced and well versed in the intricacies of contemporary global politics, are fully aware of the risks that this may entail.”

It appears that Russian concerns in this regard are similar to those linked with the LEMOA agreement back in 2016 allowing both Indian and US navies to utilise each others’ military facilities for refuelling and refurbishment. In reality, Moscow could not sign the same kind of deal with India, even though the Reciprocal Exchange of Logistics Agreement (RELOS) has been on the table since 2018. As the conflict in Ukraine is far from a resolution and Russian naval ships are rare guests in the Indian Ocean, RELOS will unlikely be finalised any time soon.

Although there is an understanding that the growing partnership with the US will not affect India’s ties with Russia, officials and experts in Moscow continue to view geopolitics as a primary driver of US policy toward India. According to Ryabkov, Russia will continue to deepen its strategic partnership, including defence ties, with India, despite “US chicanery” and “intensified attempts to bring India into its geopolitical structures”. Different experts tend to believe that Washington is keen to impact India’s position on Russia and China. They point out that the US, on the one hand, has been seeking to involve India in the “anti-Chinese initiatives” and, on the other, expects the Indian government to halt increased imports of Russian oil and to shut the door on technologies’ reexport.

Overall, Russian experts believe the India-US engagement has its limits and New Delhi will not agree to turn into an ally of the US. New Delhi’s enduring approach toward the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and refusal to condemn Russian actions are viewed as a manifestation of that.

Timofey Bordachev, professor at the Higher School of Economics, Moscow, calls Modi’s visit to the US “an absolute triumph” and “a great achievement for Indian diplomacy” as it has provided New Delhi with “an excellent chance to get modern technologies and investments in the Indian economy”, which are badly needed for India’s development agenda.

The focus on technological cooperation is visible both in the US and Indian leaders’ joint statement and the iCET initiative curated by the national security advisers. The highest level of engagement in the history of India-US relations allows New Delhi to get closer to receiving American advanced technologies and solutions, such as semiconductors, AI, quantum computing, and telecom equipment.

Surprisingly, India’s decision to join the Artemis Accords and the new agreements between NASA and ISRO were largely disregarded by the Russian media. This is not an area of US-Russia competition anymore with the latter’s space programme facing various troubles over the last decade, resulting in a serious shrinking of Indo-Russian space cooperation. Although Indian cosmonauts received training at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre near Moscow in 2020-2021, it is increasingly evident that India will be partnering with the US for its human spaceflight programme and space research, taking advantage of various collaborations with Artemis Accords signatories and attracting investments into private space projects.

India’s engagement with the US’s technological sector is a logical step to stimulate domestic development programmes and foster the digital economy. Due to the inevitable impact of sanctions, Russia may lag further in this domain and will be likely reliant on Chinese achievements and the illegal imports of Western technologies.

Even as India is not turning away from Russia, it is set to expand and deepen its partnership with the US in areas where Moscow can no longer take the lead.

The writer is Visiting Fellow, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations and Research Fellow, School of International Affairs, Higher School of Economics, Moscow