Opinion Why Sylvia Plath still speaks to us

She was not writing just about herself — she was writing about all of us. In this strange liminality of being in my twenties, where childhood is fading but adulthood still feels like an ill-fitting costume, reading Plath feels like both a mirror and a map

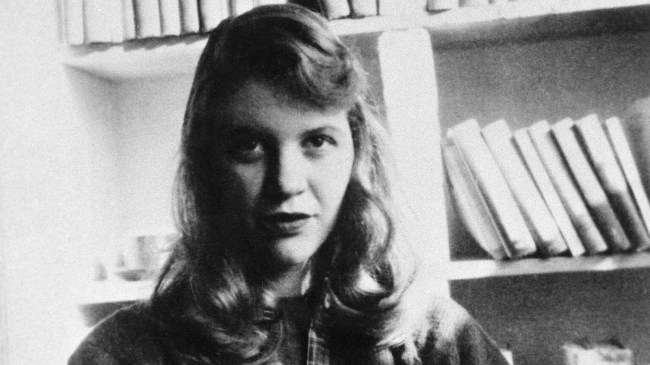

Sylvia Plath is known as one of the most important voices in confessional poetry. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Sylvia Plath is known as one of the most important voices in confessional poetry. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) “Should I be concerned?” a friend asked when I said Sylvia Plath was my favourite poet. It was half-joke, half-suspicion — like reading Plath was a diagnosis.

I had hesitated before telling her who my favourite poet was — not because I was ashamed, but because naming a favourite author/poet feels like severing limbs, like saying one piece of my soul matters more than the others. But I said her name. And the response followed, like clockwork. A joke about ovens. A quip about suicide. A smirk dipped in feigned concern. If I had a rupee for every inappropriate joke I’ve heard about Plath, I’d have been able to afford therapy before I even knew I needed it. February 11 marked her 62nd death anniversary.

I was 13 when I first read Plath. “The eye of a little god, four-cornered,” she writes in her poem Mirror. The words struck me like cold water. Knowing that it was written in the years leading up to her suicide felt unsettling to me. But I was 17 when I was introduced to her semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar, passed on to me by a friend who knew, somehow, that I needed it. I read it slowly, deliberately, turning back to certain passages. And for the first time, my overly-judgemental and self-critical high-school self, felt seen — not in the way teachers talked about “relatable characters” — but in the way truth grips you and refuses to let go, and you realise you are not alone.

Plath is known as one of the most important voices in confessional poetry. She published her first collection of poems, The Colossus and Other Poems, in 1960, and three years later, she died by suicide.

For someone in her early twenties trying to make sense of herself amid constant, gnawing uncertainty, to exist is to walk a tightrope between paradoxes: To be ambitious but not ruthless, independent but not alone, desirable but not desperate. In this strange liminality, where childhood is fading but adulthood still feels like an ill-fitting costume, reading Plath feels like both a mirror and a map. Her work is draining and energising at once; I return to it when I no longer know what I am searching for, only that I am searching.

To be in one’s twenties is also to constantly wrestle with worth — whether it is tied to productivity, desirability, intellect, or the invisible race against those who seem to have figured it out. But Plath writes, “I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want. I can never train myself in all the skills I want. And why do I want? I want to live and feel all the shades, tones and variations of mental and physical experience possible in my life. And I am horribly limited.” This acceptance, instead of defeat, feels like liberation. There is freedom in knowing that the hunger for everything is, in itself, a kind of living.

This portrait of Sylvia Plath is divided by half with a monotone shadow side representing depression, and the colourful side representing creativity. (Express Photo/ Mansi Jagani)

This portrait of Sylvia Plath is divided by half with a monotone shadow side representing depression, and the colourful side representing creativity. (Express Photo/ Mansi Jagani)

In The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood’s summer in New York is one of contradictions — brimming with opportunity yet isolating, glamorous yet suffocating. She breathes in “the dry, cindery dust” of the city, and with it, the quiet dread of knowing that the things she is supposed to want do not feel like enough. There is no handbook for being in your twenties — only a chorus of expectations, a list of achievements to be ticked off. Yet, what if effort alone isn’t enough? What if the bright lights only make the shadows sharper?

The world tolerates a woman’s sorrow only when it is made small — softened into something easy to swallow. The “sad girl” trope has often been used to trivialise Plath’s readers as fragile, self-indulgent — people who make sadness their personality. But Plath was not weak. She did not merely wallow in sadness; she dissected it, traced its roots, unravelled its mechanisms. In ‘Lady Lazarus’, she does not romanticise pain – she makes it visceral: “I do it so it feels like hell/ I do it so it feels real.” There is no languid suffering here — only the stark, painful assertion of existence.

To read her is to realise that sorrow does not render one lesser; it does not make one broken, just acutely self-aware. It is an act of defiance. To feel deeply, to refuse to shrink, to name the sadness instead of tucking it away — that is a form of resistance. And with that, she instils faith in others to do the same. Plath was not just writing about herself — she was writing about all of us. About the infuriating, beautiful, terrifying reality of being young and uncertain. Of wanting to live but fearing the weight of it. Of being trapped between who you are and who you are supposed to be.

most read

Plath’s poetry is terrifyingly personal because it does not flinch. Perhaps this is why, decades after her words were first written, they continue to remain so deeply relevant. Because they do not offer easy answers, do not show a path, do not tell you how to fix the loneliness or the fear. Instead, they hold a mirror to the tangled, feral parts of being alive and say, “This too is worth something”.

And isn’t that the great tragedy? That she understood so much, carried so much, gave so much — and still, the world was not enough to hold her. And so, we read her, over and over, carrying her words like talismans and feeling the quiet terror of recognition.

Perhaps the only thing left to do is what she did — to write, to shape the unbearable into something that endures. To keep moving, feeling, thinking even when it seems impossible. To carve out our own space in the world and call it ours. To find a way to exist — fully, completely, passionately — before the world tries to take us under. And, in the process, we come face to face with the complexities not just of the world but also within us — a complexity that is imperfect and, therefore, beautifully human.

mansi.jagani@indianexpress.com