Opinion Remembering the 1971 war, as seen by a child

🔴 Ann Ninan writes: Amidst the excitement of mock drills and the thrill of witnessing an air raid, it was a shock to realise that the enemy looked just like us

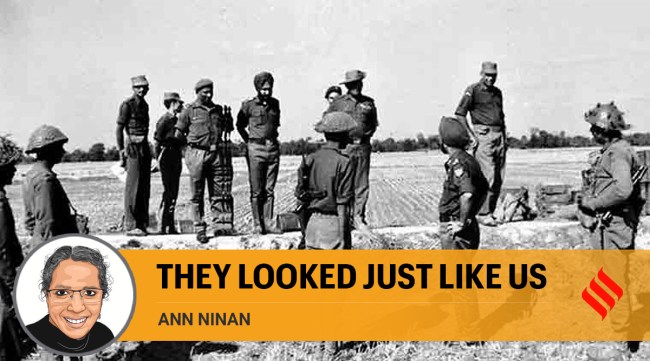

If there was anxiety in our homes about the possibility of a real war with Pakistan, we didn’t notice. Everything was a blast. (File)

If there was anxiety in our homes about the possibility of a real war with Pakistan, we didn’t notice. Everything was a blast. (File) For schoolchildren 50 years ago, December was the dreaded month of final exams, when the first 10 minutes, at least in the cold parts of north India, were spent coaxing frozen fingers into writing legibly. December 1971 in Udhampur, Jammu and Kashmir, was both an exam month and bone-chilling. Except that we lived in the daily hope of an air raid setting us free from the exam and racing into the trenches when the siren went off.

As the crow flies, Udhampur is a mere 40 kms from the India-Pakistan border. For weeks before the war broke out on December 3, our cantonment was in a perpetual state of preparedness. Our fathers, who had long abandoned civvies, would take us to the weekly black-and-white film screening at the old-fashioned Chinar Cinema, sten guns in hand. It was only after the war that the old cinema was torn down and replaced with a 70 mm screen, reclining seats and popcorn.

For us kids, the run-up to the war was high excitement: The mock air raid drills with their two rounds of sirens, one announcing the attack and the second sounding the “all clear”; the trenches around every home, glass panes covered with black paper so that no light would escape.

If there was anxiety in our homes about the possibility of a real war with Pakistan, we didn’t notice. Everything was a blast. For instance, one day the daily sundown ritual of the Last Post coincided with an air raid drill. It triggered a round of insuppressible giggling because we didn’t know whether we were to stand to attention in our trenches as the ceremony demanded or remain squatting with our heads down in case of flying shrapnel from exploding artillery.

When the real thing happened — an air raid followed by a dog fight right above our heads — I remember we stood up in our trench to watch, much to the dismay of the subedar major saheb, who, in the absence of our fathers, took his job as guardian angel very seriously. The ack-ack of anti-aircraft guns, the whirr of incoming helicopter ambulances ferrying the wounded to the Udhampur Military Hospital and the unusual orange glow on the western horizon, which we believed was from the battlefield, seemed like experiences straight out of the Second World War comics that we devoured as children.

Our mothers’ contribution to the war was also of a piece. They went in batches to the military hospital to roll bandages! One time, we went along and wandered in and out of wards, probably looking for gore, which we didn’t find. But we did chance upon a young captain, who was stationed in Udhampur. In my mind’s eye, I can recall his bemused expression at being stared at by a bunch of kids. What is unbelievable is that no one stopped us or asked what we were doing, let alone who we were.

It was at the hospital that I saw my first “Pakistani”. We heard about him before we saw him. We must have asked for directions to his room because I remember creeping up on tip-toes to find the door open, a solitary hospital bed in the centre on which the man lay, one leg winched up by a pulley. I recall the shock of realising that he looked no different from any of our fathers. And when he waved at us cheerfully, we wheeled around and fled.

By the time the POW camp came up across the mostly dry nullah from where we lived, we were reconciled to the idea that the enemy looked exactly like us. We tried not to stare at the dozens of prisoners as we trotted past the camp on horseback every evening, within touching distance of the barbed-wire fence. One day, the camp was deserted and we were told the Pakistani soldiers had all gone home.

By the time the POW camp came up across the mostly dry nullah from where we lived, we were reconciled to the idea that the enemy looked exactly like us. We tried not to stare at the dozens of prisoners as we trotted past the camp on horseback every evening, within touching distance of the barbed-wire fence. One day, the camp was deserted and we were told the Pakistani soldiers had all gone home.

That was 50 years ago. A time so far removed from today’s flag-waving India and cheerleading media that it feels like an implausible dream in black and white.

This column first appeared in the print edition on December 16, 2021 under the title ‘They looked just like us’. The writer is a journalist who has worked on development issues in South Asia