Opinion Nobel, Booker and how two Hungarian writers redrew the world’s literary centre

If Krasznahorkai is the reclusive Hungarian prophet of “apocalyptic terror”, Szalay is the Hungarian-British chronicler of rootless modernity

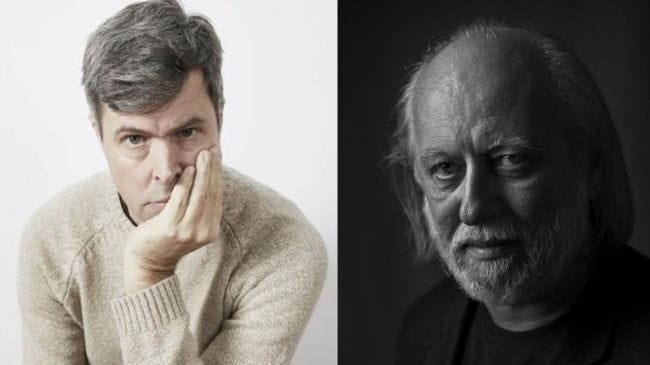

The Booker Prize 2025: László Krasznahorkai and David Szalay are both authors of Hungarian heritage.

The Booker Prize 2025: László Krasznahorkai and David Szalay are both authors of Hungarian heritage. This autumn, the power centre of world literature has been redrawn, with its new capital situated in the imaginative landscape of Hungary.

In a span of just over a month, the two most significant awards, Nobel Prize in Literature and the Booker Prize, have gone to two Hungarian authors — László Krasznahorkai and David Szalay, who are connected by a nation, yet separated by their aesthetic universe.

If Krasznahorkai is the reclusive Hungarian prophet of “apocalyptic terror”, Szalay is the Hungarian-British chronicler of rootless modernity. Together, it is a long-overdue acknowledgement of a Central European sensibility that has been speaking its unsettling truths all along.

Heir to Franz Kafka and Thomas Bernhard, Krasznahorkai’s Nobel win was a recognition of his “compelling and visionary oeuvre”, a body of work that finds art’s power where the world ends. To read Satantango (1985) or The Melancholy of Resistance (1989) is to be immersed in a prose that is itself a performance of decay and persistence. His sentences, famously long and winding, are like rivers overflowing their banks, carrying all before them in a torrent of philosophical despair and grotesque beauty, best captured in the seven-hour, black-and-white film adaptation of Satantango by his friend, Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr.

As the anatomist, dissecting the specimens the abyss has produced, Szalay, on the other hand, is Krasznahorkai’s complement. Born in Canada, raised in London, and now living in Vienna, Szalay carries his Hungarian heritage as a central tension in his work.

“Even though my father’s Hungarian, I never feel entirely at home in Hungary,” Szalay said during the Booker Prize ceremony. “I suppose I’m always a bit of an outsider there and living away from the UK and London for so many years, I also had a similar feeling about London, I guess. So I really wanted to write a book that stretched between Hungary and London and involved a character who was not quite at home in either place.”

Written in spare prose, Flesh, Szalay’s sixth novel is a world away from Krasznahorkai’s dense thickets of text. It spans “from a Hungarian housing estate to the mansions of London’s rich elite,” tracing the unravelling of an “emotionally detached man”. This is Szalay’s great theme, the fragility of the modern male psyche, adrift in a globalised world of transaction and dislocation. Where Krasznahorkai’s characters are consumed by cosmic forces, Szalay’s are undone by the mundane failures of connection and identity.

His win, for a novel written in English, is a testament to the power of the diasporic voice, one that translates the specific anxieties of a Hungarian past into the universal currency of contemporary angst. To journey from the haunting, metaphysical plains of Krasznahorkai’s Hungary to the sleek, disorienting corridors of Szalay’s Europe is to undertake a complete pilgrimage through the anxieties of our time.

What, then, does this convergence signify? It is not that a single “Hungarian style” has triumphed. The two writers represent the opposite poles of a spectrum. Krasznahorkai’s work is embedded in the soil and history of his homeland, its prose rhythm as ancient and inevitable as a folk tale. Szalay’s is fluid, transnational, and immediate. Krasznahorkai gives us the grand, terrifying prophecy of systemic collapse; Szalay provides the intimate case study of the individual who must navigate its ruins. Together, they bookend the modern human condition, wavering between collapse and endurance.

The writer is deputy copy editor, aishwarya.khosla@indianexpress.com