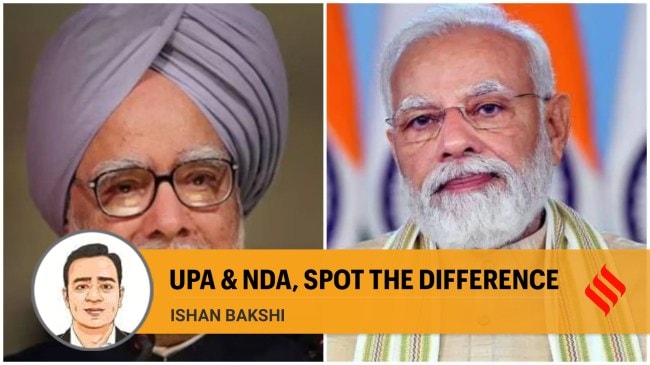

Opinion On the economy, how UPA and NDA governments have been remarkably similar

Irrespective of the ideological leanings of the next government, the forward march of the Indian economy is more likely to rhyme with its past

Between 2004-05 and 2013-14, when the UPA alliance was in power, the Indian economy grew at an average of 6.8 per cent per year. In comparison, growth during the BJP decade has been lower, averaging 5.9 per cent. (File)

Between 2004-05 and 2013-14, when the UPA alliance was in power, the Indian economy grew at an average of 6.8 per cent per year. In comparison, growth during the BJP decade has been lower, averaging 5.9 per cent. (File) In a few months from now, the Narendra Modi-led government will complete 10 years in power. Whether in action or in rhetoric, the BJP government has repeatedly sought to differentiate its policy approach and style of governance from that of the Congress-led UPA alliance which was in power the decade before.

The differences between the governments may simply be due to the very structure of the two political formulations. The ruling dispensation is helmed by a single party with a commanding majority, which apparently provides policy stability. In comparison, the earlier dispensation was held together by a loose alliance of parties, where policy was often hostage to coalition compulsions.

The differences could also be due to their contrasting ideologies which are reflected in the differing policy priorities. For instance, the BJP government can claim to have implemented far-reaching economic reforms such as the IBC and the GST, while the Congress-led UPA ushered in NREGA and the Right to Food, which form the backbone of the country’s welfare architecture.

The differences may also arise from the ability of the ruling dispensation to galvanise the administrative machinery more efficiently and effectively to meet its ambitious targets. This reflects in the accelerated public provision of essentially private goods and services, less leakages from the system and greater welfare gains.

There may well be other points of differentiation. However, there are also some remarkable similarities between the two decades in matters of the economy and the government’s place therein. It would seem that the more things have changed, the more they have remained the same.

Perhaps, the greatest anomaly between rhetoric and reality lies in economic growth. Between 2004-05 and 2013-14, when the UPA alliance was in power, the Indian economy grew at an average of 6.8 per cent per year. In comparison, growth during the BJP decade has been lower, averaging 5.9 per cent. However, the Modi government can claim, and rightfully so, that had it not been for the pandemic, growth under its tenure would have been considerably higher. On its part, the UPA government can also claim that the global financial crisis depressed growth during its term.

It may just be a fascinating coincidence, but excluding the years of the global financial crisis and the pandemic, growth rates over the two decades are identical. During the UPA years (excluding 2008-09), growth averaged 7.2 per cent per year, while during the BJP years (excluding 2020-21), it stands at 7.2 per cent.

Strangely enough, these two decades have seen consumption booms and busts, investment activity surge and sink, trade rise and fall, strong and frail corporate and bank balance sheets, coalition and majority governments, and certainty and uncertainty on both political and policy fronts. Yet, the end result has been the same. Will the coming decade be any different?

Next, take the capacity of the government to raise resources. This is not only a measure of the efficiency of the tax administration, but it also determines government spending. On this as well, the two decades are broadly comparable. During UPA’s term, the Centre’s gross tax revenues to GDP ratio averaged 10.5 per cent. For the BJP years, it works out to 10.8 per cent.

In recent years, however, there has been a surge in both direct and indirect tax filers, in part a consequence of greater formalisation and the shift to GST architecture that incentivises compliance and allows for greater traceability of transactions. This has pushed up the tax-to-GDP ratio, but only slightly. The revenue gains from the expansion in the tax base have been limited due to deep cuts in both direct and indirect taxes.

Considering that tax giveaways are ideology agnostic, the question now is: As India traverses from a lower to an upper-middle income status economy over the coming decade, as the tax base expands further, will the odds that the next government continues with the policy of tax giveaways change?

On privatisation, the track record of the BJP government is only marginally better. This is disappointing, considering the apparently stark ideological divide between the two dispensations, most succinctly captured by the phrase that the government has no business to be in business. To be fair to the current government, it has indeed taken some bold steps — for example, selling off Air India and LIC’s stake sale, among others. But, these have been few. Stripped of all the hyperbolic rhetoric, there isn’t a coherent privatisation strategy. There was much talk about selling off some public sector banks. But that has gone nowhere. It would seem that neither the ideological leanings nor the political capital vested with the ruling government seem to matter enough. Perhaps, the Indian state is simply unwilling to cede control.

This near stagnation in resource mobilisation shows in government spending. Under the UPA, central government spending to GDP averaged 14.9 per cent, while under the BJP it is marginally lower at 14.2 per cent. But, what has changed is spending priorities. The Centre’s capital expenditure, after averaging just under two per cent of GDP, has begun to edge upwards, touching 2.5 per cent in 2021-22 and 2.7 per cent in 2022-23. And if this year’s spending target is met, then the capex-to-GDP ratio would have risen to 3.4 per cent. Alongside this concerted redirection of spending, a greater portion of the Centre’s borrowings is now being used to finance capital expenditure. The question is whether this will continue over the coming decade.

These trends do suggest that irrespective of the ideological leanings of the next government, whether it is helmed by a single party or a coalition that is held together more by compulsion than conviction, the forward march of the Indian economy and the state is perhaps more likely to rhyme with its past. Ruptures are likely to be few.

ishan.bakshi@expressindia.com