Opinion Mohan Bhagwat’s support for the LGBTQ+ community is conditional and exclusionary

Why the appropriation of the queer community by the Hindu right is disturbing

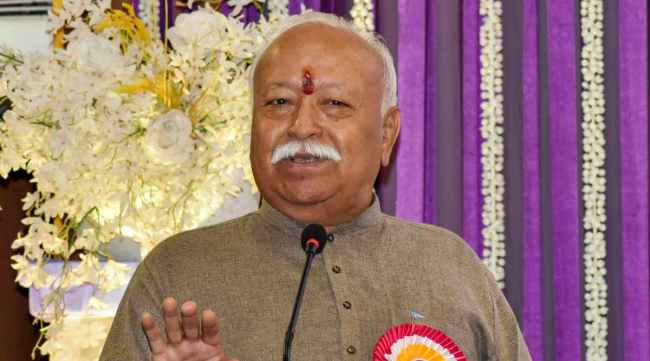

RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat addresses an annual prize distribution programme, in Nagpur, Friday, Jan. 13, 2023. (PTI Photo)

RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat addresses an annual prize distribution programme, in Nagpur, Friday, Jan. 13, 2023. (PTI Photo) Written by Sudipta Das and Anushree Samant

In a recent interview with the magazine, Organiser, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat extended his “support” to the LGBTQI+ community in India. RSS’ “acceptance” of the queer community has put many of us in a strange position. Are we supposed to celebrate this statement or unpack it to see what it actually means for us and the movement? As queer and/or trans people ourselves, how do we make sense of the range of reactions and responses to the interview, across the community?

Even the smallest snippet of the interview in question reveals that Bhagwat’s language and tone was tolerant, not accepting, and came across like a performance. RSS’s stance has been quite extreme on queer issues over the years. This sudden shift in tone also comes with caution. We must not create much hullabaloo about our lives. They accept (read: tolerate) us and that solves all our problems.

“Acceptance” itself is an inherently political act that tactfully presupposes that our existence needs the consideration of other people. Throughout the interview, Mohan Bhagwat reiterates how “LGBT, Tritiya Panthi” people have always been a part of Indian culture and mythology — largely imagined to be Hindu-centric. People have, throughout history, found ways of co-existing with queer and trans people without much of a hullabaloo, which apparently is the best practice. We should continue existing the way we have in the past — “silently”.

Growing up, many of us were silenced. “Be whatever you are, in private,” we were told when we tried to open up to our families. The interview, uncannily similar in tone, reminded us how silence has been a violent tool, used to dismiss our reality and deny us authenticity in our own homes. The flipside of: “Be whatever you are, in private” is: “Don’t be yourself in public spaces”. We grew up in a world where silence spoke louder than any words uttered.

Taken rhetorically, the speech also perpetuates a certain idea of “acceptance” by fitting us in the same cis-het archetype of marriage and heteronormative families. It is unfortunate that many people residing outside of queer-trans realities have not only failed to but also refused to see the way we have reimagined the idea of a “family” — creating radical possibilities by centering compassion, community, care. Throughout history, queer people have thrived within hijra gharanas, chosen families, living with multiple partners, loving and letting go.

At a time when the queer community itself is deliberating on the question of same-sex marriage, Bhagwat’s comments are especially important. Rajeev Anand Kushwah, a research associate at CLPR, in their paper, wrote: “Many radical queer activists are against the notion of conservation of property, continuation of bloodline and placing the nuclear and conjugal family on a pedestal … This is particularly relevant to caste endogamy. There is a fear that same-sex marriage might lead to the furtherance of savarna gays and lesbians to marry each other and would not really undermine caste hierarchies.” Marriage has historically been the institution that perpetuates caste purity, religious monogamy, class adherence, and of course, heterosexuality. How do we then position ourselves within the contours of marriage politics?

There are many important issues alongside same-sex marriage that influence our day-to-day lives — housing, healthcare services, horizontal reservation, employment, to name a few. The onus of dismantling every oppressive system that has been created and perpetuated by people in positions of power should definitely not be on queer and trans people. We can and should be able to comply with systems that give us safety, access, and social recognition. But, the respect and safety we are afforded shouldn’t be contingent on how well we conform to these standards/systems.

Bhagwat’s interview and politics in general is centred around the “Hindu Rashtra”. Everything said is within that context. When queerness is articulated in deep cohesion with religion, a relevant question is: What of those of us who are queer but not Hindu? India is a secular country; we have queer people with diverse religious identities. The monopolisation of the queer community by the Hindu right is not only concerning but also detrimental to the radical politics of abolishing the hierarchy of religion and caste to imagine true queer liberation. Many of us are queer and not Hindu, many of us are queer and Hindu and have a difficult relationship with our religion. Mohan Bhagwat shared some snippets from Hindu mythology, “Jarasandh had two generals – Hans and Dimbaka. When Krishna fanned a rumor that Dimbaka had died, Hans committed suicide. What does this story suggest? That the two generals were in that sort of a relationship.” This is one of many stories from mythology. The issue with one story isn’t that it’s untrue, but telling it as a standalone tale is deceptive, and paints an incomplete picture. Most Indian mythology has savarna dominance and Brahmanism built-in. We are complex beings with many identities. Co-opting one and continuing to sabotage the other doesn’t serve any real purpose. It only reflects the neglect and lack of awareness, which brings violence into our lives. Queer Liberation can’t be seen in isolation, we need to build solidarity across various movements. That is the only way to ensure that we do not leave behind people who exist on the margins, even and especially in queer and trans spaces.

Again, accepting us is not even the beginning of the journey. We need to make “acceptance” the norm, regardless of religion and caste. That’s the “Queer Rashtra” we imagine.

Das is a Dalit-queer feminist writer working with The YP Foundation. They write on media, caste, sexuality and queer rights.

Samant is a queer-affirmative trauma-informed therapist who works independently.