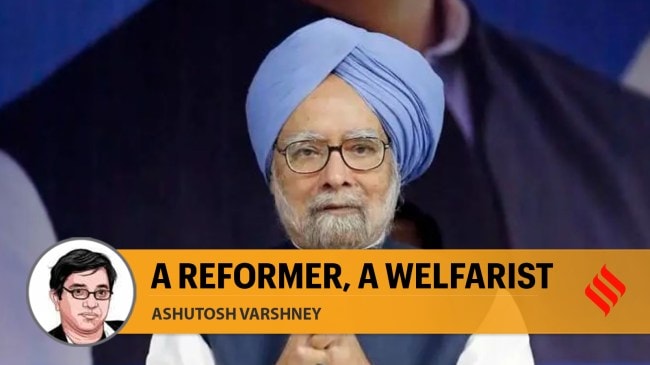

Opinion How Manmohan Singh created the middle class – and didn’t think welfare was government largesse

Unwavering civility would perhaps be the best way to describe what I experienced. Even when in positions of high power, arrogance never touched him, and civility never failed.

Beyond economics and welfare, the civil nuclear deal with the US was a massive achievement of Manmohan Singh as India’s Prime Minister.

Beyond economics and welfare, the civil nuclear deal with the US was a massive achievement of Manmohan Singh as India’s Prime Minister. Alone in the post-independence history of India, Manmohan Singh rose to the highest office of the land based on his policy accomplishments, not because of a mass political base. He altered India’s economic future in 1991. Though his contributions are manifold, as I discuss later in this column, the fundamental transformation in the direction of economic policy is his truly monumental legacy.

Let us recall the circumstances of the first half of 1991. The balance of payments had lurched from one crisis to another, and in mid-July, India had so little foreign exchange left that only two weeks of imports could be financed. Put simply, India was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Earlier, a macroeconomic crisis of this kind typically required a short-run economic stabilisation plan under an IMF-led stand-by arrangement. The aim used to be getting at least two macroeconomic balances – the external balance of payments and internal fiscal deficit — in control. To India’s great fortune, Manmohan Singh, as the nation’s finance minister in 1991, saw the crisis as an opportunity to attend to the long-term economic issues, not viewing it only as a short-run problem, which, of course, it also was. In a historic speech given to Lok Sabha on July 24, 1991, he argued that “macroeconomic stabilisation and fiscal adjustment alone cannot suffice. They must be supported by essential reforms in economic policy… (facilitating) a transition from a regime of quantitative restrictions to a price-based mechanism.”

The argument, in other words, was that India’s economic policy, based as it was on state-directed quantitative planning since Independence, required a market-based reformulation. Otherwise, such macroeconomic crises would continue to erupt, and economic progress would be stalled. There had to be a movement towards economic freedom and state retraction from the economy.

Internally, this led to what Jagdish Bhagwati called “a bonfire of investment licences”. Instead of the state telling investors where to invest, how much and with what kind of technology, domestic entrepreneurs were now free to invest in most sectors of the economy. Externally, trade pessimism, typical of the earlier era, was to be abandoned, and a market-oriented trade regime was embraced, supplemented with openness to foreign investment. “We have reached a stage of development”, argued Manmohan Singh in the justly famous July 1991 Lok Sabha speech, “where we should welcome, rather than fear, foreign investment. Concern is sometimes expressed that… foreign investment may jeopardise our economic sovereignty. These fears are misplaced. We must not remain permanent captives of a fear of the East India Company as if nothing has changed in the past 300 years.”

Thus began India’s economic transformation that, unreversed by later governments, has lasted till today. In 1980, India was the 50th largest economy in the world. By the time Singh left office in 2014, the Indian economy was among the top 10 in GDP (and has become the fifth-largest by now). A large middle class has come into being, literally for the first time in modern Indian history. India always had some very rich people and a large mass of the poor, but the middle class was minuscule. Not so any more.

Finally, given the World Bank’s poverty line ($1.90 a day at 2011 prices), nearly 250-300 million people have been lifted out of poverty since 1991. This poverty-alleviation record is substantial but not as phenomenal as China’s, where over 700 million have ceased to be poor in the post-Mao era.

Indeed, the inability of markets to not lift more people out of poverty led Manmohan Singh to institute a new set of policy innovations in his second coming – when he became India’s Prime Minister (2004-14). In this phase, the makings of a modern welfare state were put in place, with a focus on the poor and the marginalised. In 2005, rural India got a right to employment for 100 days a year via the world’s largest employment guarantee program (MNREGA). In 2009, a right to education was created, and in 2013, a right to food security. All of this was undergirded by a right to information (2005), which citizens could exercise to find out how serious the government’s rights delivery was.

It is important to emphasise that this was a rights-based welfare regime. All programmes for the subaltern were legislated as the rights of the less privileged. Using modern social science terminology, it can be argued that many governments in India, including the present one, conceptualise welfare as acts of government kindness or what social scientists call patrimonialism. The idea of 800 million citizens covered with ration is an example. Rights-based welfare is not simply embodied in government schemes. It is anchored in legislation and laws, which then spawn schemes (yojnayein). These are two very different concepts. Manmohan Singh’s welfarism viewed the underprivileged as rights-bearing citizens, not simply as recipients of largesse.

Beyond economics and welfare, the civil nuclear deal with the US was a massive achievement of Manmohan Singh as India’s Prime Minister. The deal ended what used to be called the nuclear apartheid and took the US-India relationship to a new level. The tensions that used to mark the US-India relationship during the Cold War had lost their rationale as the Cold War ended. Still, a systematic diplomatic effort had to be made to turn the post-Cold War phase into a set of policies and programmes. Both for geopolitical and economic reasons, a close relationship with the US is beneficial for India. Manmohan Singh saw the desirability of it and managed to institute a new phase in the Indo-US relationship. India’s diaspora was, in any case, heavily inclined towards the US. Even during the Cold War, there was no great citizen enthusiasm for the Soviet Union. Government policy finally gravitated closer to citizen wishes.

A word may also be said about Manmohan Singh’s personal conduct — before, during and after his years in power. I had several meetings with him, starting with his days as the head of the Reserve Bank of India and later when he held important positions in Delhi. Unwavering civility would perhaps be the best way to describe what I experienced. Even when in positions of high power, arrogance never touched him, and civility never failed.