Opinion In ‘Millennium City’ Gurugram, problem isn’t flooding or infrastructure — it’s the rural state of mind

Urban life in Gurugram is largely organised through the idea that there is no public except that which belongs to one's family, caste and class circuits. It is this that also lies at the heart of what passes for urban planning

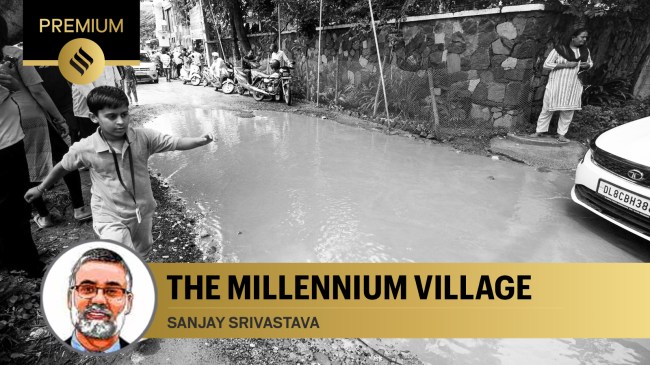

Urban life in Gurugram is largely organised through the idea that there is no public except that which belongs to one’s family, caste and class circuits. (Express/Praveen Khanna)

Urban life in Gurugram is largely organised through the idea that there is no public except that which belongs to one’s family, caste and class circuits. (Express/Praveen Khanna) The so-called Millennium City’s waterlogging problems are in the news again. In Gurugram, flats and houses that sell for prices that compare to real estate in Western countries and rentals that might equate starting salaries of many white-collar professionals have become islands surrounded by surging rain-induced floods. As a result of the waterlogging, there were also sustained cuts to the electricity supply as the privately owned transformers that kick in when the government supply fails also went underwater. There was, reasonably enough, an outcry over the state of infrastructure in a locality that is home to the offices of many Fortune 500 companies and a citizenry that has achieved wealth in many walks of global activity and expects a certain level of an “international” lifestyle.

But Gurugram’s problem is not primarily physical infrastructure. It is one of the mental attitudes through which our cities are built and occupied. Physical infrastructure is not so difficult to build and operate. How we choose to live in urban environments — that are supposed to rid us of “backward” rural attitudes — has always been a more complex task. It is made more complex in places such as Gurugram because new urbanism has simply built upon old attitudes rather than changing them. The most fundamental of these is the idea of publicness or the distinction between the private and the public.

When we think of contemporary urbanisation in India, the easy way out is to blame its ills on privatisation and that largely meaningless concept of “neoliberalism”, where the state is supposed to have ceded ground to private capital. Public interest would have been much better served, it is frequently suggested, had public authorities looked after the welfare of citizens. This gross oversimplification overlooks the history of publicness in our everyday lives, one that also lies at the heart of the state of Gurugram and other such urban developments.

The first “licence” for private development was issued to the Delhi Land and Finance (DLF) corporation on April 21, 1981, under the Haryana Development & Regulation of Urban Areas Act of 1975 in the village of Chakkarpur in Gurgaon district. Everyday social life in Chakkarpur, as in all villages around it, was organised through the arrangements of caste: Public life was entirely expressed through caste hierarchies and beliefs. Who could say what, pray where and clean the garbage were matters of caste. There was no generalised public life but, rather, one that was entirely expressed through the personal attributes of caste. You looked after your own. “New Gurgaon” has simply built on that, keeping the old social attitudes alive while giving off the idea of newness. New highways, metro stations and shopping plazas appear to speak of a new public life, but that is a mirage.

Urban life in Gurugram is largely organised through the idea that there is no public except that which belongs to one’s family, caste and class circuits. It is this that also lies at the heart of what passes for urban planning. If, for example, it is considered personally beneficial to cement over a waterway or clear a forest area for a private residence, then that activity comes to pass. The wider ramifications are rarely considered as there is really no sense of a public and hence, public welfare beyond the immediate circles in which people live. This, however, has little to do with the privatisation of urban development in cities such as Gurugram. It is fundamentally connected to a ruralism practised by the urban well-to-do.

At the present time, the most significant urban development in Gurugram is taking place in what were earlier its rural hinterlands, the areas furthest away from Delhi. Lands are being bought, sold and cleared for residential, commercial and infrastructure purposes. It is not difficult to see how, while multiple modern technologies are being used for mapping and digitising records to make land market-ready in these areas, the state, private capital and citizens have combined to further the ends of private benefit through wilfully rejecting the idea of publicness and public welfare.

Land consolidation and rectangularisation (chakbandi and kilabandi) are important for the rationalisation of holdings that might otherwise be scattered or irregular lands that prevent the construction of roads and other infrastructure. However, in most cases, these are also contexts when panchayat lands — meant for general benefit — are appropriated for personal use and profit. The assistance of a variety of government officials — able to bend GIS technologies that are meant to produce transparency to the needs of private benefit — is, of course, crucial. As urbanisable land is built upon and becomes urban, the attitudes towards publicness displayed in appropriating public lands for private benefit simply scatter in different directions. The re-fashioning of rural spaces into urban ones is not accompanied by a different attitude towards publicness and public welfare.

Gated residential enclaves, where the problems of public life are simply pushed out to the spaces and people beyond the walls, are not really a dramatically new phenomenon. They are merely the concrete manifestations of mentalities that linger under the appearance of change. The roads and underpasses that surround the luxury apartments and which get routinely flooded and engulfed by rainwater do so because of the mental infrastructure through which city planning and design happens. That rural state of mind that appropriates public lands for private profit is simply reproduced within urban spheres where the idea of the public — if it ever existed — has largely disappeared.

City planning does not require “smart” planning and “smart” technologies such as CCTV and “control and command” centres designed by global consultancy companies with little idea of local conditions of life. The most fundamental aspect to be incorporated into planning for city life is the idea of publicness and the sense that without this we have nothing but a hollow modernity. We spend an enormous amount of time debating the past and the nature of the private and public lives of past generations. It is our strange wariness in giving the same attention to the problems of the present that lie at the heart of the flooded streets of Gurugram and other cities that challenge our claims to civilisational achievements.

The writer is Distinguished Research Professor, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, SOAS University of London