Opinion In Karnataka, Congress and BJP are two sides of the same coin

The Congress campaign so far shows no signs of turning BJP’s disastrous failings in Karnataka to its advantage. If anything, it appears as if Congress, and not the BJP, will be hobbling to the ballot box

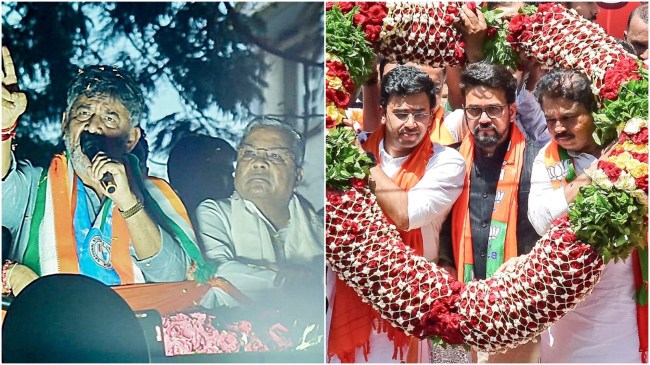

Will Karnataka remain content with its tenuous autonomy, preserving its Opposition-led state government even as it yields power to the BJP juggernaut in Parliament? (Express photos)

Will Karnataka remain content with its tenuous autonomy, preserving its Opposition-led state government even as it yields power to the BJP juggernaut in Parliament? (Express photos) In one of his brilliant cartoons from the 1970s, Abu Abraham sketched two Congressmen, one tall and thin and one short and fat, walking towards a UP ballot box with the helpful arrow: “Vote Your Caste Here!” Abu was surely the master of anastrophe, that is, the figure of speech that inverts words for emphasis, or, in his case, to amuse people. The inversion jolts people into recognising how commonsensical some “truths” have become and serves as a powerful critique of that common sense.

Behind the caste calculus

It is no secret that caste calculations have long remained a staple of our political discourse; parties will strenuously deny their importance, and yet put it firmly in place when it comes to allocations of seats. The current Prime Minister’s charisma and the BJP’s control of all institutions today notwithstanding, the party has not dropped a trick in shrewdly keeping its caste flocks together. Gone are the days when “even a lamp post could win under a Congress ticket” — or are they?

What’s new about happenings on the caste front in Karnataka? The candidate selection, challenging at the best of times, reveals a good deal about what the two principal political formations stand for. The BJP break-up includes just six SC/ST candidates, but nine Lingayats, four Vokkaligas, and three Brahmins. In short, 16 out of 28 seats are already earmarked for the dominant castes, who have seized a fresh opportunity to assert a presence that had been checked by the operation of Indian democracy. Congress, on the other hand, has fronted one Muslim (where there were none in the BJP), and no Brahmins, though plumping for eight Vokkaligas and five Lingayats. But against this dominance of the dominant castes, it has double the number of OBCs that the BJP has put forward (six). Congress also edges out the BJP on the SC/ST seats, with eight candidates. And the Congress beats the BJP on the gender front with a total of six candidates (compared to just two in the BJP).

Pipe dream of Hindu unity

All the math boils down to some hard facts: First, the choices and the heated contests over several seats reveal that the much-touted Hindu unity remains a pipedream. This is bad news, especially for the BJP which has, for long — and loudly — proclaimed the opposite. In 2022, the RSS head Mohan Bhagwat conspicuously visited Chitradurga, where a clutch of new mathas run by dominated castes has emerged, to reassure the mathadishas that there is no such thing as “caste” in the scriptures, that discrimination was merely a perception, and that they must bide their time before “all is well”. The BJP’s choice of Pralhad Joshi in Dharwad has revived a nearly 140-year-old hostility between the Lingayats and Brahmins.

Second, the BJP reveals itself as the “party of order”, in both its inclusions and exclusions. Thus, the “beleaguered” Brahmin finds his “rightful” place, while the “dangerous” Muslim is obliterated. Third, in choosing to team up with Deve Gowda, lock, stock and son-in-law, the BJP dents its own image as the “party against dynastic politics”. Fourth, in embracing the “robber baron” of Bellari, Janardhana Reddy, the BJP hacks at its own “swachh” feet. Fifth, in pegging hopes on the Wodeyar “heir”, the BJP shows that it looks to erstwhile “royals” — even if they are OBCs — to do their bit in realising Hindu Rashtra.

Faltering Congress

Congress, meanwhile, may justly claim the moral high ground in spreading itself more democratically across castes/genders/ethnicities. But it lives up to its reputation as a party of political heirs, with a large number drawn from political families. Two, despite its democratic choices, the bitter quarrels over candidates will not easily die down. In the crucial Kolar constituency, a fierce fight between Dalits on the Left and the Right led the party to “import” a more neutral candidate from Bengaluru.

Three, despite fielding more women, senior Congress members could not suppress an irrepressible misogyny (The BJP has not been far behind on this front). Four, and most importantly, its ambitions are not matched by vigorous campaigning. Let us remember that PM Narendra Modi aggressively snatched away from the Karnataka Congress the word “guarantees” after its May 2023 success. But whether the guarantees, which unlike most political promises were fulfilled in entirety, will now turn into votes is in considerable doubt.

Finally, moral righteousness of another kind, that demands a fairer share of taxes and revenues from the Union government, may yield little affective capital against the brazen BJP campaign that forces all candidates — including those of the Opposition — into the penumbra of the Great Leader. We know that the “double engine sarkar” that existed before May 2023 did little to assert Karnataka’s rights, whether on cultural, developmental, or economic issues. But the Congress campaign so far shows no signs of turning those disastrous failings to its advantage. If anything, it appears as if Congress, and not the BJP, will be hobbling to the ballot box.

How will Karnataka vote?

Will Karnataka then remain content with its tenuous autonomy, preserving its Opposition-led state government even as it yields power to the BJP juggernaut in Parliament? Can Karnataka hold the Union government to account, whether on questions of immediate importance, such as drought, or longer-term issues related to language? Does the Congress’s “My Tax My Right” have the chance of demonstrating that states will not be reduced to administrative units for the implementation of the Union government’s programmes? Above all, can Congress now rally ordinary people around the federal principle? And will “caste” now slope off into the background?

Like Abu Abraham’s two Congressmen, in Karnataka at least, Congress may share more with the BJP than it cares to admit. He had described them thus: “one gone lean in the service of the masses, the other gone fat in the same effort; one who has always believed that power corrupts, the other who doesn’t need the power to be corrupt.” The Congress’ inclusive caste equations and amply fulfilled guarantees prove no match to the fatal attractions of the Prime Minister, who always, everywhere, wrests advantage from adversity.

The writer is a Bengaluru-based historian