Opinion How to prevent disruptions by flood and extreme weather events

Climate change is a harsh reality. It's time to accept that and re-imagine our cities.

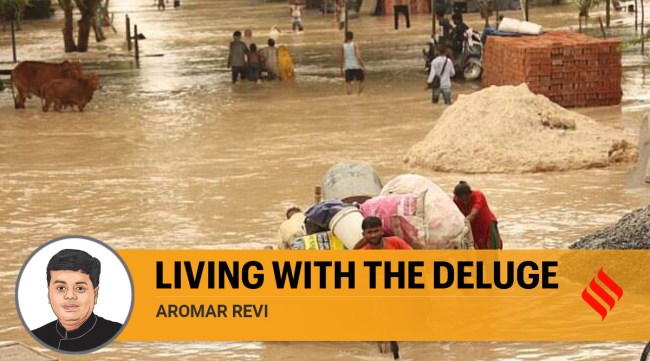

Climate impacts and risks like flooding are felt intensely in our cities. This is because they concentrate one-third of our people and two-third of our economic output in increasingly dense built-up areas, with poor water, sanitation, drainage and wastewater infrastructure that struggle to even deliver everyday basic services. (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Climate impacts and risks like flooding are felt intensely in our cities. This is because they concentrate one-third of our people and two-third of our economic output in increasingly dense built-up areas, with poor water, sanitation, drainage and wastewater infrastructure that struggle to even deliver everyday basic services. (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal) Stranded citizens, flooded homes, cars floating through inundated streets, and the emergency evacuation of people are now part of stock images of cities across the country. The deluge in north-western India and Delhi over the last week is no exception to this trend. This is now a recurrent, lived monsoon experience for many of our cities from Mumbai and Chennai to Bengaluru.

As global warming increases and local warming in our cities goes well beyond the 2oC guardrail, the intensity of climatic-impact drivers like too much or too little rain and heat will increase, as will the frequency and intensity of extreme weather. As our work in the IPCC, and that of the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), has shown, this may not grow incrementally each year. It could grow exponentially, much faster than our current governance, planning and infrastructure systems are able to adapt to. This will lead to massive future disruptions across urban India – flooding, water scarcity and heatwaves – that we need to prepare for and adapt to.

Climate impacts and risks like flooding are felt intensely in our cities. This is because they concentrate one-third of our people and two-third of our economic output in increasingly dense built-up areas, with poor water, sanitation, drainage and wastewater infrastructure that struggle to even deliver everyday basic services. Irrational land use and planning systems exacerbate these challenges and amplify the vulnerability of tens of millions who are forced to live in informal settlements and slums. Cities in sensitive regions along the coast, rivers and hills face even worse impacts, due to higher exposure and locational vulnerability.

Because of these complex interacting factors, traditional siloed responses to the climate crisis are doomed to fail. Yet city and state administrators from Surat to Indore to Gorakhpur and Kochi have successfully implemented several commonsense climate adaptation and flood response measures. What can cities do better to reduce the loss of life and limit economic and property losses for millions?

Ensuring drainage exists and works: Most urban civic bodies conduct a monsoon audit ahead of the season. This is to ensure that storm water drains, tanks and lakes exist and work, and they are not choked by construction debris, silt, garbage or blocked by encroachments. This is a complex task that needs planning all through the year and adequate financial and human resources, which are rarely a priority. If done well, this can blunt the impact of flooding, along with helping recharge groundwater and surface storage, when the rain arrives.

The medium-term solution is the integration of drainage, water supply and wastewater systems to store the intense rain that may come over a short period as well as treat and recycle wastewater to ensure safe water and sanitation through the rest of the year. This will enable better services and limit waterborne diseases.

We also have to ensure that our drainage systems have enough capacity to take the greater intensity of rain that will come with a changing climate. We have started taking steps to improve our basic infrastructure in large cities, through schemes like AMRUT but the pace is far behind the accelerating changes in rainfall and urban expansion.

Improving roads: The expansion of our urban areas faster than planned drainage systems means that many roads effectively become stormwater drains. To reduce local flooding, we need to improve the way city roads are built and repaired. Every time a tar road is repaired, it gains a few inches, as tar is laid on top without milling down the existing road. In time, road level rises above surrounding areas, buildings, and drains which are not surprisingly inundated during a downpour. This is made worse when most flyovers, underpasses and sometimes metro lines built to address traffic, land up disrupting existing drainage, leading ironically to massive traffic bottlenecks post-flooding. This needs to be addressed with effective infrastructure planning and coordination by all concerned agencies, as has been demonstrated in many cities.

Greening cities and using blue-green-grey infrastructure: As our cities expand to become impervious concrete jungles, there is less place for water to percolate and flow. Conserving and protecting urban forests, wetlands, rivers and lakes are critical to addressing climate change-induced flooding, water scarcity and heat waves and improving livability. China is trying to transform 30 of its megacities into “sponge cities” that use green roofs to slow down run-off into drains, urban forests to enable percolation, groundwater recharge and wetlands to absorb and reuse two-thirds of their water. For over a century, East Kolkata’s wetlands have been an effective flood defence mechanism that help treat a large share of the city’s sewage, produce half of the city’s fresh vegetables, and provide livelihoods to one lakh people. Practical nature-based blue-green-grey infrastructure such as these hold the key to climate adaptation for many Indian cities.

Reducing flood vulnerability: India has the technological capacity to map all of its cities and towns, using high-resolution satellite and local topographical data to identify areas most prone to flooding. The challenge is to address the vulnerability of millions of people, who live along river banks, low-lying areas and unstable slopes, whose everyday lives are dislocated during extreme events. We have become much better at evacuation and protecting people’s lives but have a long way to go in enabling real community-based resilience.

Improving early warning services: After a devastating series of urban floods in cities like Mumbai and Surat in the early 2000s, India has done well to improve its forecasting, early warning and evacuation systems in many large cities. This has to be extended to most places that are at risk along with strengthening critical cellphone, power and water supply services so that they are resilient and can recover rapidly from extreme events.

We need to protect and prepare our cities for future flooding, drought and heat waves that will arrive at our doorsteps with climate change. The most effective way to do this is to ensure that all urban residents have access to basic environmental services: Water, sanitation, drainage and solid waste management. We need to reduce our collective vulnerability, improve public health and re-imagine our cities to have more forests, parks, wetlands and lakes that are not gobbled up by irrational and often illegal changes in land use and poorly regulated real estate interests. Finally, it’s time to accept that we live in a warming world, in which climate change is a harsh reality that all of us — poor or rich — need to adapt to.

The writer is Director of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements and an IPCC Coordinating Lead Author