Opinion How technology can empower Indian citizens and re-energise local governance

Before the information age, seeking inputs from citizens involved mind-boggling efforts. Today, state actors set up dedicated channels to include citizens’ insights with the click of a button

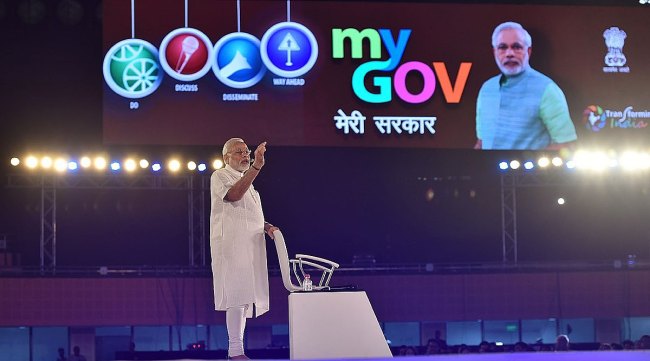

Today, over three crore citizens can provide inputs and feedback on government policies, and programmes through the MyGov App. (Wikimedia Commons/PIB)

Today, over three crore citizens can provide inputs and feedback on government policies, and programmes through the MyGov App. (Wikimedia Commons/PIB)

With over 2.5 lakh gram panchayats, and over 2,000 municipalities and municipal corporations, India’s local governance ecosystem is unparalleled in terms of its scale, reach and intent. From towering cities to humble villages, local governments are often presented as the means to deepen democracy and improve governance through people-led decision-making. Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a leading political scientist, in an article (‘Not so local government’, IE, March 11) argued that the implementation of the 73rd and 74th amendments in 1992 remains our best hope for the same but posits that it has been held back as the state is fundamentally not serious about decentralisation. On the other side of the debate is Nitin Pai, the founder of Takshashila, a public policy school. In an article, he says, “The argument that the amendments had flaws or its implementation was undermined by the Indian political economy avoids confronting the more fundamental issues.”

There is a significant factor that one must consider in this debate, one that has far-reaching consequences and is changing rapidly. Technology. The relationship between citizens and the state has drastically changed due to extensive penetration and use of technology. It has made decentralisation an evolving real-life negotiation between tens of crores of citizens and state actors (and local leaders). Citizens now have concrete channels to directly influence the state and vice versa. It is thus imperative to factor into the debate the three broad ways in which technology has impacted the citizen-state relationship.

First, the exponential growth of social media platforms broke communication barriers between sections of our society. It has become simpler to organise like-minded individuals and present a united front. Public grievances like open sewers, poor roads, a bribe-seeking official etc., are no longer “routine”. One could organise large groups on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and be heard. People could coordinate protests and get petitions signed through WhatsApp groups.

State agencies responded by channelising issues raised on such platforms into a structured grievance redressal system. For example, the IRCTC has an active and live mechanism to redress public grievances raised on social media. The Chief Minister’s Office of Haryana seeks grievances raised on social media and works to get them resolved via relevant government departments. The Ministry of Consumer Affairs also recently launched a WhatsApp bot to receive grievances from citizens. In a pre-social media era, one could hope for a resolution only if they could find a way, the time, and the means to make their voices heard.

Leading politicians have set up their own mechanisms to replicate their success on social media platforms. It is a matter of time before grassroots leaders, panchayats, councils etc., join the bandwagon. Citizens will soon be able to choose from multiple avenues that can help address their concerns best.

Second, the adoption of technology as a means of engaging with citizens is gaining traction amongst state actors. Earlier, seeking inputs from citizens involved mind-boggling efforts — advertising, collating letters, reading, synthesising, etc. Only the savviest of citizens had the access, knowledge and means to contribute meaningfully. Today, state actors set up dedicated channels to include citizens with the click of a button (maybe a few clicks).

Today, over three crore citizens can provide inputs and feedback on government policies, and programmes through the MyGov App. The Department of Education in Himachal Pradesh conducted “parent-teacher meetings” through video calls on WhatsApp, meaning parents didn’t have to skip a day’s work to engage with teachers. The Supreme Court and some high courts routinely hear cases via video conferencing and stream them live for the larger public. District courts have set up Telegram groups to directly share relevant information like listing of cases, orders, notifications etc., with lawyers and litigants. Earlier, one had to physically visit the court and read notice boards. Local entities like Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) have improved public engagement with active support from startups like MyGate and ApnaComplex. Inputs and the needs of citizens are being actively included in designing and improving the delivery of services.

But all of these technologies come at a cost and hence only those with the resources (financial and otherwise) can develop and leverage its benefits. Pratap in his article posits that “Technology has been a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it can create local capacity; on the other, it has been used to largely bypass political negotiation and control.”

This brings me to the third way technology has changed governance. A more recent development, but one that could arguably transfer power into the hands of citizens is open-source technology. Technologies like Aadhaar, UPI, and CoWin, are built as publicly-owned, open-source digital infrastructure. By its very nature, the source code of these technologies is publicly available, and a citizen could suggest edits to the code (“push” as the tech term goes) independently. During the countrywide Covid-19 vaccination drive, multiple citizens “pushed” code to CoWin after they experienced bugs and glitches on it. An active, open-source community contributing to digital public infrastructure can increase the direct influence citizens exercise on the state. Given the improvements in AI tools, citizens directly contributing to DPGs will become increasingly easy. It won’t be long until a sarpanch would be able to seamlessly leverage technology for the governance of their panchayat.

Technology (including AI) is a critical factor in the debate around decentralisation and implementation of the 73rd and 74th amendments in their true spirit. Pai put it succinctly: “We should be thinking of more effective models that can improve grassroots governance in Indian conditions in the information age.” The time to ponder is past, now’s the time to act.

The writer is Senior Manager at Samagra, a mission-driven governance consulting firm