Opinion Green-eyed angel

The role Norman Borlaug,who died on Saturday,played in the import of the dwarf miracle wheat seeds in the mid-60s has...

The role Norman Borlaug,who died on Saturday,played in the import of the dwarf miracle wheat seeds in the mid-60s has almost a Puranic Katha status: with Sivaraman Saheb the agriculture secretary playing the Arjuna,C. Subramaniam the minister the Krishna,and Borlaug the role of the Pitamah.

I landed in Delhi in 1974 after having modelled Gujarats perspectives,and given my econometrics degree was pulled in to head the then-powerful Perspective Planning Division of the Planning Commission,which has always been a friend of agricultural scientists. Borlaug would visit India. Great scientists at a particular level,like economists,live in the world of the laws of biology,botany and geology. Borlaug could easily slide into that world; but at another level,unlike economists,they dont believe only in solving problems in theory. Borlaug was one such icon,like Verghese Kurien. He would come to the Planning Commission; and one could take one look at the way the director-general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and his men would tiptoe in with him and know he was the works. They would come to Sivaramans office and I would be asked to hang around because he had a disconcerting habit of asking questions about canals,pump-sets,fertilisers and wheat prices precisely the questions the ICAR abhorred. These were the things they could blame the economists for,and so I had to chip in. Jeff Sachs,who has spent a lot of his time rubbishing Indian efforts,now prescribes for Sahelian sub-Saharan Africa the Indian 70s model of giving money for tubewells and a good price. For Borlaug the world was more complicated. Owning the Indian wheat revolution,he was not going to let that rot in the fields.

By those days,the gains of the 60s were gone. Indias grain production had reached 116 million tonnes in 1971 and then went down to around a 100 million tonnes. The Sussex Institute,the World Bank and assorted forecasters were coming out with dire forecasts. India wont feed itself,they said,and its medium-term growth prospects were zilch. Borlaug shared the pain of Indians living ship-to-mouth and kept up the vision. But on his annual pilgrimage he would get into the details. Why are the canals not working? What about the rabi fertiliser? If not imported,because energy prices had rocketed,what about giving electricity from Bhakra to the Nangal fertiliser plant (starving the towns; austerity again). What about credit,prices and procurement? What about loans for tubewells in Bhatinda? Why was the Mohindergarh Lift Canal in Haryana not getting money? His networks would keep him posted and he would badger the mightiest in the land and get a hearing. Of course the needs of his scientist buddies got top billing.

The early attacks on the green revolution bothered him,particularly Keith Griffin and others saying that it was bypassing the small farmer and generating poverty. He was genuinely appreciative of Indian studies showing that the world of adopters was more equal than that of non-adopters (G.S. Bhallas Large Haryana study) and that small farmers went above the poverty line in Anand (Vijay Vyas work). He believed hunger could be ameliorated with widespread agricultural growth,and the Indians were his counterfactual to the Doubting Thomases in the world.

In the 80s,as I moved up in the planning and policy-making hierarchies,I was to meet him more often on my successive trips to Delhi. To the best of my knowledge,he was the first author of the bifocal strategy: that India will have to raise grain yields and release land for an agricultural economy diversifying to meet the needs of faster growth. He was chastened by some of the costs of the favoured crop favoured region model and worried about land,water and carrying capacity. Later he was appreciative of the Indian UPOV (Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants) legislation and the Swaminathan model of a case-by-case examination of BT seeds and felt that it was a good compromise between the American/ Chinese push for very bullish policies and nay-sayers in Europe. But he was not too happy with the regulators being bureaucrats in what he felt was a scientific question of safety impacts. It delayed the process and brought in many irrelevant considerations to the debate.

A very wise universal man,in the sense of the poetry of the Gayatri Mantra. India and the world are poorer.

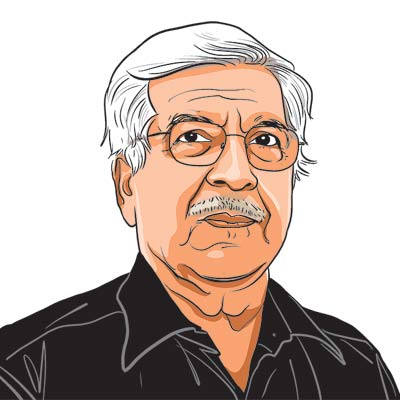

The writer,a former Union minister,is chairman,Institute of Rural Management,Anand

express@expressindia.com