Opinion Former CEC S Y Quraishi writes: An EPIC exclusion

EC's refusal to accept the identity card it created, in SIR in Bihar, appears arbitrary and self-contradictory

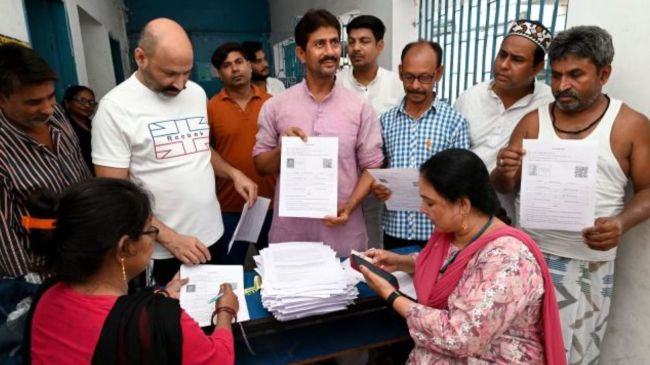

If the EPIC is good enough for the nation’s first citizen to bestow with such pomp, surely it must be good enough for the Commission to recognise. (File)

If the EPIC is good enough for the nation’s first citizen to bestow with such pomp, surely it must be good enough for the Commission to recognise. (File) Few documents in independent India have so profoundly shaped the democratic experience as the Electors Photo Identity Card (EPIC). Introduced by the Election Commission of India (ECI) in the 1990s, the EPIC has transformed the way we vote, conduct elections, and even prove who we are in daily life. It is therefore astonishing that the very institution that created the EPIC now refuses to accept it.

In July, the ECI announced a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar. A welcome step in principle: Voter lists have historically been vulnerable to errors, duplication and under-registration. A clean and credible roll is the bedrock of a free and fair election. But the details of the exercise contain a startling twist.

Applicants for enrolment or correction have been asked to furnish any one of 11 specified documents to prove their residence and identity. Conspicuously absent from this list are the EPIC — the Commission’s own flagship identity card — and Aadhaar, the nation’s most widely-used proof of identity. The omission has rightly raised eyebrows, triggered litigation, and prompted the Supreme Court to express surprise.

The exclusion of the EPIC and Aadhaar from Bihar’s SIR was challenged in the Supreme Court. During hearings, the Court was openly puzzled: “EPIC and Aadhaar are readily available documents. Tomorrow, 10 out of 11 accepted documents could also be fake — that cannot justify blanket exclusion of these”, said Justice Surya Kant. The Bench repeatedly urged the ECI to focus on mass inclusion rather than exclusion, and specifically suggested that the EPIC and Aadhaar be accepted.

However, surprisingly, in its final order, the Court directed only Aadhaar’s inclusion (that too for the 65 lakh deleted voters and not for all 7 crore applicants). It stopped short of mandating the EPIC’s acceptance. This nuance has allowed the ECI to claim compliance with judicial directions while still refusing to rely on its own most powerful tool of voter identification.

It is important to remember that the EPIC was not a bureaucratic whim — it was a reform born of conviction and confrontation. In the late 1980s, concerns about impersonation and bogus voting were eroding public trust. Under the redoubtable TN Seshan’s uncompromising leadership, the ECI launched an ambitious programme to photo-identify every voter.

The project met with immediate resistance. It required substantial funds and political backing. When Seshan approached Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao for funding, Rao reportedly refused, citing budget constraints. Seshan, in characteristic style, is said to have warned that unless the request was granted, he would not call the by-election Rao needed to contest to continue as Prime Minister — a constitutional requirement under Article 75(5). The funds were sanctioned within days.

This episode is more than an anecdote. It symbolises the assertion of the Commission’s independence and its determination to strengthen the integrity of elections. The EPIC was, from its inception, a reform secured against odds — not a gift of political generosity but the fruit of institutional insistence.

The current exclusion is not only baffling — it is deeply symbolic. Every year on January 25, India celebrates National Voters’ Day, an event created precisely to encourage enrolment. Millions of young voters receive their EPICs at polling booth level on this day. At the national function, no less than the President of India personally hands over EPICs to a select group of new voters — a moment of pride telecast across the country, in the presence of over 30 election commissioners of the world.

That the very card ceremonially handed over by the Rashtrapati is now disqualified as proof of identity in Bihar’s revision process is a bitter irony. It risks turning a proud democratic ritual into an empty spectacle. If the EPIC is good enough for the nation’s first citizen to bestow with such pomp, surely it must be good enough for the Commission to recognise.

Besides, there is a very important question: In the coming election, will the EPIC be required or accepted from each voter? Moreover, if it has been discarded by its creators/owners, will they issue EPICs to the new voters as was always done? The practical consequences of excluding the EPIC, the most possessed ID, are serious. Bihar is a state with high migration and large numbers of rural poor. Many citizens possess only the EPIC as their proof of identity. Denying its validity risks making the process cumbersome, dissuading participation, and disenfranchising genuine voters.

Given its rich history, the exclusion of the EPIC from the SIR document list is baffling. It creates a paradox: The same card that was good enough to run the 2024 General Election, with 642 million voters participating, is suddenly deemed inadequate for revising the rolls. When the rules appear arbitrary or self-contradictory — when a card used to elect a government cannot be used to stay on the roll — public confidence erodes.

The solution is straightforward. The EPIC should be reinstated as an admissible document with reasonable safeguards as ECI may choose. This approach would protect roll purity while ensuring no genuine voter is excluded for lack of alternative documents like passport or driving licence. The ECI must also communicate clearly with voters. Why was the EPIC excluded? Is there evidence of large-scale misuse that justifies this step? How will the Commission guarantee that legitimate voters are not struck off?

By answering these questions explicitly, the ECI can turn controversy into a moment of civic education — restoring confidence and proving its commitment to impartiality. The EPIC was conceived as a weapon against electoral malpractice. It has been celebrated globally as a symbol of India’s democratic capacity. To sideline it now, without a compelling explanation, sends the wrong signal.

The credibility of an election depends as much on the perception of fairness as on the mechanics of the process. In a country of India’s scale, no institution can afford to appear arbitrary or inconsistent.

It is time for the Election Commission to reaffirm its faith in the card it created — and in the voters whose faith it must protect.

The writer is former Chief Election Commissioner of India and the author of An Undocumented Wonder — The Making of the Great Indian Election