Opinion Failure to acknowledge existence of manual scavenging is deplorable

Manoj Kumar Jha, Pragya Srivastava write: Both the central and state governments are notorious for enshrouding the problem. There has always been an attempt to fudge the data, and contradictions are found in government data itself.

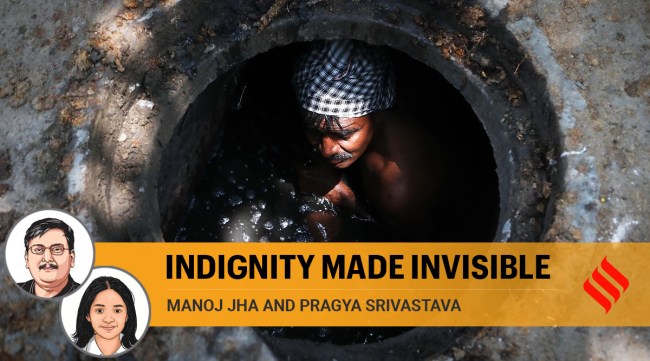

Manual Scavenging being done in New Delhi. (Express Photo: Abhinav Saha)

Manual Scavenging being done in New Delhi. (Express Photo: Abhinav Saha)

Throughout our history, we have undergone profound changes in power dynamics and political ideals that have transformed individual lives as well as the idea of the collective. But the modernising forces have been deeply biased. Caste is an overbearing reality. It is not simply a tag of identity but dictates a way of life. It continues to reinforce inequality as a basic value and the allocation of labour is one of its prime manifestations. Caste hierarchy reinforces occupational hierarchy and the idea of occupational purity and pollution are further embedded in the lives of individuals.

As B R Ambedkar pointed out, caste leads not only to the division of labour but of labourers as well. Dalits often face discrimination when seeking employment in sectors that are considered “pure”. Manual scavenging or cleaning of dry latrines, for instance, is a job that the Dalit classes have been burdened with. Although the practice was banned under the Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers Act, 2013, the inhumane exercise continues. According to government data, 97 per cent of manual scavengers are Dalits. The breakdown of numbers reveals that 42,594 manual scavengers belong to Scheduled Castes, 421 belong to Scheduled Tribes and 431 belong to Other Backward Classes. These statistics are disturbing, a reminder of our collective failure to rise above caste lines and provide dignity of labour to all. These numbers also beg the question: Would manual scavenging still exist if it was not relegated to Dalits?

Work is fundamental to how we realise our destiny in this world; to provide economically for oneself and one’s family is central to dignity — a lack of it leads to alienation and stunted human growth. Dalits are expected to clean dry latrines, carry loads of human excrement, and clear sewage for little or no income. They are trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty and social exclusion. Even when manual scavengers get an education and a degree, the burden of caste is heavy. Ambedkar had observed that “in India, a man is not a scavenger because of his work. He is a scavenger because of his birth irrespective of the question whether he does scavenging or not”.

Caste-based prejudice has been normalised to such an extent that the plight of manual scavengers does not get the attention that it deserves. Both the central and state governments are notorious for enshrouding the problem. There has always been an attempt to fudge the data, and contradictions are found in government data itself. In a reply to a question in Parliament, the government said that there is no report of people currently engaged in manual scavenging and no death has been reported due to the practice in five years. The government carried out two surveys in 2013 and 2018 for the identification of manual scavengers and that is the latest data we have. According to the Census (2011), there are 26 lakh dry latrines and as of 2017, only 13,384 manual scavengers had been identified by the government.

Simple math and logic reveal obvious exclusion errors in identifying manual scavengers. In the latest reply to a question in Parliament, the Ministry for Social Justice and Empowerment revealed that 66,692 manual scavengers have been counted and the majority are from Uttar Pradesh. Assessments from civil society reveal that the numbers are much higher. Moreover, when questioned about what steps the government had taken to replace manual scavenging by machines, it said that since the practice has been banned, the question does not arise. According to some well-researched media reports, the Indian Railways, the army, and urban municipalities remain the biggest bodies that still have workers engaged in manual scavenging. They either find ways to outsource such work to contractors so as not to be held directly accountable or liable or simply misrepresent such workers as “sweepers”.

The government’s response reflects a deep sense of apathy. While one acknowledges that progress has been made on mechanised sanitation, to say that the question of updating technology does not arise adds injury to insult. Denial only contributes to the delay in solving the problem. There has been a rushed attempt to declare India “open defecation free”. We have stopped acknowledging that sewer deaths are still a reality. According to the Safai Karamchari Andolan, at least 472 people have died cleaning human excreta during the last five years. One would expect the Swachh Bharat Mission to solve sanitation problems but to exhibit the success of the PM’s flagship programme, we have made invisible the labour of sanitation workers.

We are still a long way from the rehabilitation of manual scavengers. The government scheme provides for one-time cash assistance of Rs 40,000, skill development training, and capital subsidy for self-employed projects. But the lack of a reliable database makes these efforts futile. Strict enforcement of the law is also needed. As of now, the provisions for punishment are both weak and more importantly, as highlighted by activists, there have been next to no serious legal proceedings against people and organisations accused of engaging workers for manual scavenging. Activists further demand that the law needs to be read along with the SC & ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, to strengthen it.

The diminishing government support was also evidenced in the 2021 budget — the rehabilitation fund was trimmed. Further, it is important to understand that this is not just a problem of technology or financial assistance but also of social prejudice. The state must accept the role of caste and should actively solve it.

Manual scavenging in the 21st century sounds an abhorrent alarm about caste domination. The failure to acknowledge it is deplorable. We must show impatience and a sense of urgency. Equality, the dignity of labour, and justice have waited for too long.

This column first appeared in the print edition on February 23, 2022 under the title ‘Indignity made invisible’. Jha is MP, Rashtriya Janata Dal and Pragya Srivastava is a LAMP fellow.