Opinion BJP goverment must rethink scrapping of Free Movement Regime in Manipur and beyond

The decision has not gone down well with the Nagas, Mizos, Chins, and Kuki-Jo communities who share strong ethnic and kinship ties with the people of Myanmar

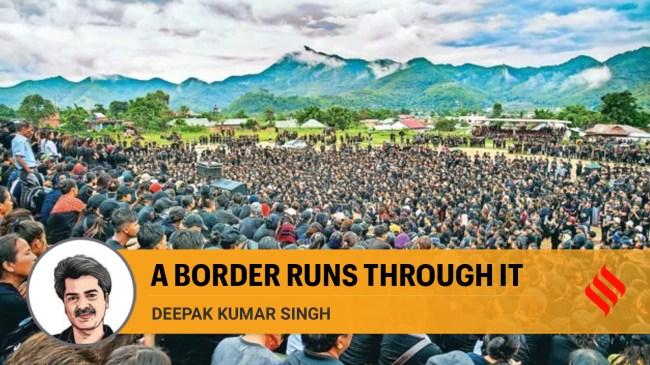

Members of Indigenous Tribal Leaders' Forum (ITLF) take part in a protest rally as a mark of protest against the harrowing incident that occurred on May 4, in Churachandpur district, Manipur, July 20, 2023. (PTI Photo)

Members of Indigenous Tribal Leaders' Forum (ITLF) take part in a protest rally as a mark of protest against the harrowing incident that occurred on May 4, in Churachandpur district, Manipur, July 20, 2023. (PTI Photo) On February 8, the Union Home Ministry suspended the Free Movement Regime (FMR) between India and Myanmar with immediate effect. It has also urged the Ministry of External Affairs to terminate the FMR in consultation with its Myanmarese counterpart. The move to undo this unique arrangement perhaps has little to do with the unfolding humanitarian crisis resulting from the military junta-led coup d’etat three years ago. It has a more immediate domestic cause — the colossal failure of governments — both at the Centre and the state — to control the ethnic conflagration that broke out between the majority Meitei and minority Kuki-Jo ethnic communities in Manipur on May 3 last year. Put differently, the suspension of the FMR is an attempt to vindicate Chief Minister N Biren Singh’s claim that the ongoing ethnic conflict is essentially due to the activities of “illegal immigrants” and “drugs and arms traffickers”, all of whom could presumably enter the state from across the border in Myanmar. In a meeting with the Union Home Minister Amit Shah on September 23, 2023, Singh made a strong pitch for scrapping the FMR and fencing the 1,643 km-long border with Myanmar, which passes through Arunachal Pradesh (520 km), Nagaland (215 km), Manipur (398 km) and Mizoram (510 km). By suspending the FMR, Shah has lent credence to Singh’s claim of a “foreign hand” playing the lead role in the Manipur crisis. In addition, Shah has also promised to fence the entire stretch of the India-Myanmar border with a state-of-the-art hybrid surveillance system at a whopping cost of almost Rs 6,000 crore.

The Centre’s decision goes against the grain of the region’s unique history. The current border alignment between India and Myanmar is a colonial legacy. Much of what presently constitutes India’s Northeast was under the reign of the Burmese king until about the early 19th century. It was only after the defeat of the Burmese rulers at the hands of the British and the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826 that the present boundary came into existence. With it, the British cut through age-old ethnic and cultural ties. Communities with shared ethnicity, history and culture were spatially divided, forcing them to reside as subjects and, later, citizens of different countries. Among the affected groups are the Nagas of Nagaland and Manipur, and the Chin, Mizo and Kuki-Zo communities of Manipur and Mizoram. The absurdity of colonial cartography is evident in the fact that the border bisects several houses and villages. All this has led to a groundswell of resentment among the borderlanders, who not only reject such an artificial line but also assert their inherent right to maintain strong linkages with their kith and kin across the border.

FMR-like arrangements were first started by Burma (now Myanmar) under its Passport Rules of 1948. This allowed indigenous people of all the countries bordering Myanmar to travel to it without passports, provided they lived within 40 km of the border. India also reciprocated in 1950 by amending its passport rules to allow the members of the ethnic communities residing within 40 km of the border to come in and stay for up to 72 hours. However, the Indian government unilaterally introduced a permit system in 1968 for travelling across the border to contain the rise of insurgencies. The geographic limit of 40 km was reduced to 16 km in 2004. Finally, an Agreement on Land Border Crossing, more popularly known as the FMR, between the two countries came into effect in 2018, wherein the residents living within 16 km could go to the other side with just a border pass and stay for two weeks per visit. The BJP government touted the FMR as a part of its “Act East Policy”.

Since its inception, the FMR became a lifeline and allowed both matrimonial alliances and much-needed farm and trade relations. It is against this backdrop that the governments in Mizoram and Nagaland lost no time in passing unanimous resolutions in their respective state assemblies strongly condemning the move to do away with the FMR and the proposal to seal the border. Moving the resolution, Mizoram Home Minister K Sapdanga, whose party Zoram People’s Movement enjoys the backing of the BJP, was scathing: “The British geographically divided the Zo ethnic people who have inhabited (present-day) Mizoram and the Chin Hills of Myanmar for centuries together, once under their own administration. We have been dreaming of reunification and cannot accept the India-Myanmar border imposed upon us.” Rejecting the Union Home Minister’s claim that the move was being undertaken “…to maintain the country’s internal security and demographic structure of the Northeastern States…”, Sapdanga said: “If the Centre is so concerned about national security, it should fence the international borders with Bhutan and Nepal” from where people visit India without travel documents. In Nagaland, the resolution was moved by its Deputy Chief Minister Y Patton, a key leader of the BJP, and a minor partner in the coalition headed by the Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party, who also reiterated that the Centre’s move would disrupt age-old ties.

The Centre’s decision has also invited sharp reactions from various civil society and political groups not only in Mizoram and Nagaland but also in violence-torn Manipur. The decision has not gone down well with the Nagas, Mizos, Chins, and Kuki-Jo communities who share strong ethnic and kinship ties with the people of Myanmar.

The central government would do well to pay heed to the sentiments of the people and reconsider its decision to withdraw the FMR and the proposed fencing of the border.

The writer is professor, Department of Political Science, Panjab University, Chandigarh