Opinion Bihar SIR, data indicates, is not an exercise in revision but mass deletion

If the SIR leads to a Bihar-like drop in the Electors to Adult Population Ratio in the entire country, we are looking at potential disenfranchisement of about nine crore Indians

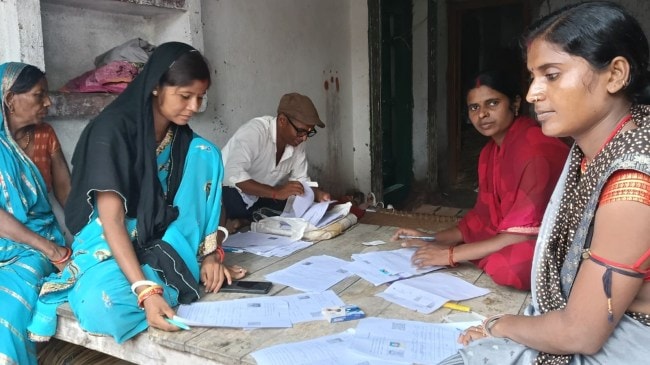

During the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar’s Nawada district. (Image source: X/@CEOBihar)

During the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar’s Nawada district. (Image source: X/@CEOBihar) The conclusion of the first phase of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar has already offered evidence of mass underenfranchisement of up to 94 lakh eligible adults. The publication of the draft electoral rolls (DER) on August 1 will break many records — all dubious. Compared to all other states, Bihar is set to be a complete outlier, a state with the highest proportion of “missing voters”. This will be the largest one-time deletion of voters at any point in the history of Indian elections. This may well be the largest exercise in disenfranchisement of voters anywhere in the world in the 21st century. And this is just the beginning. Further deletions will follow in the second phase of scrutiny of the enumeration forms, especially those the BLO has marked “non recommended”. We are assured that the same process will be followed in the rest of the country.

The numbers are already alarming. As per the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) press release of July 27, a total of 7.24 crore enumeration forms have been collected. Only these names will be listed in the DER, as compared to 7.89 crore names that existed on the state’s voters’ list on June 24, the day SIR was ordered. The ECI claims that the remaining persons are dead (22 lakh), or have permanently shifted or are untraceable (36 lakh) or were enrolled at multiple places (7 lakh) or were “not willing to register as an elector for some reason or the other”(no numbers given). As per the SIR order, these 65 lakh names will not figure on the DER. Even if there are no further deletions, Bihar’s electorate in 2025 will be smaller than the 7.36 crore electors in the 2020 assembly elections.

The ECI’s counterargument would be that the earlier voter list was severely inflated. All that the ECI has done is prune the list of dead, duplicate and dubious names. Preparing a smaller but more authentic list cannot be an exercise in disenfranchisement. This argument merits a reasoned response based on statistics. For this, we need to focus beyond the figure of 65 lakh and its breakdown offered by the ECI.

Globally, the quality of electoral rolls is judged on three counts — accuracy, completeness and equity. Accuracy is about eliminating false or erroneous entries on the voters’ list. Completeness is about not leaving anyone behind and ensuring that every person who is entitled figures on the voters’ list. Equity is about a fair representation of all social groups in proportion to their share of the eligible population. At this stage, in the absence of a list of names, we are in no position to assess the accuracy and equity of the DER in Bihar. But based on the numbers, we can provisionally evaluate its completeness.

For that, we need to follow a “missing voters” approach, drawing upon Amartya Sen’s famous argument about “missing women”. He captured this phenomenon by defining it as the shortfall of the actual number of women in a country or region compared to the expected number of women as measured by the natural sex ratio. Similarly, we calculate “missing voters” as the shortfall between the expected number of persons in the voting age population and the actual number in the voters’ list. The Census-based projections (state-wise, year-wise, age-group-wise) in the Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections (2019), by the National Commission on Population, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, are the best source for population. These figures are used by the Government of India and by the ECI itself as recently as January 2025.

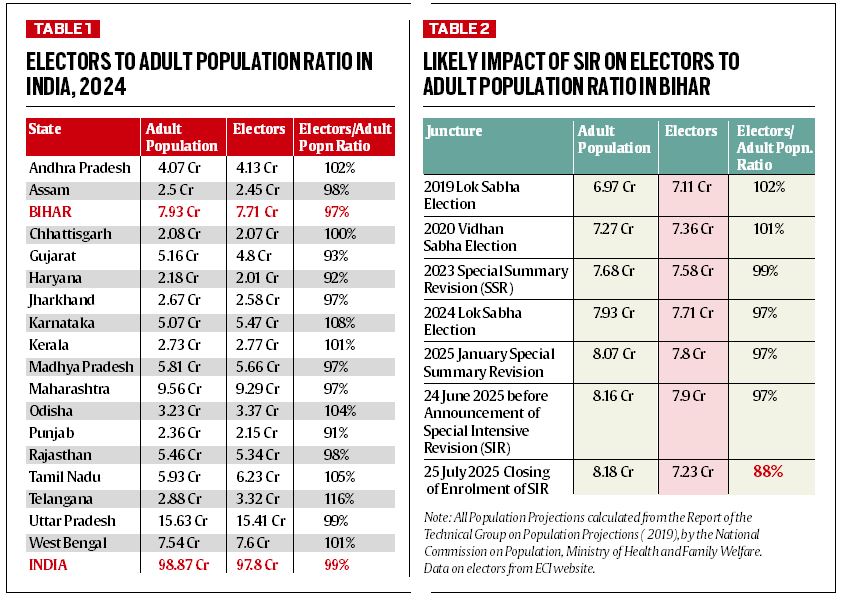

Table 1 presents the figures for adult population and the number of electors for the country and major states in 2024. The shortfall is indicated by the “Electors to Adult Population Ratio” (EP Ratio, calculated by dividing the total number of electors by the total population of the voting age group. A score of 100 per cent indicates the ideal scenario of a perfect match. It shows that in 2024, the all-India EP Ratio was a healthy 99 per cent, suggesting a shortfall of just 1 per cent. At 97 per cent, Bihar was just below the national average. Its voters’ list was not inflated but slightly deflated. Note that the denominator of the EP Ratio, the official projection of the adult population, is not subject to any inflation on account of inclusion of the dead or migrants, as the Census counts people wherever they happen to be on a given day.

Table 2 presents the same data for the state of Bihar from 2019 onwards. It shows that Bihar has hovered around the national average, with a slight decline from 102 per cent in 2019 to 97 per cent in 2024. The special summary revision completed in January 2025 and subsequent changes till June 24 added many names to the voters’ list, but since the population had also grown, the EP Ratio remained the same.

The last row in Table 2 shows the drastic and adverse impact of the SIR. In July 2025, the adult population of Bihar was projected at 8.18 crore. So that is the number we should expect on the voters’ list, against the actual number of 7.24 crore. The shortfall of 94 lakh would be the number of “missing voters” in Bihar on August 1, 2025. Even if we allow for Bihar’s prevailing EP Ratio, it should still have been around 7.93 crore. This suggests a dramatic and unprecedented fall from 97 per cent to just 88 per cent, a sudden drop of 9 percentage points in the EP Ratio. A comprehensive and de novo writing of the voters’ list such as the SIR should have led to a net addition of about 25 lakh voters. Instead, the SIR has taken a deep dive in the opposite direction by bringing the figure down further by 69 lakh.

We do not know if the SIR will lead to an improvement in the accuracy of the voters’ list, but we do know that it has worsened the completeness and in all likelihood the equity of the voters’ list. If the SIR leads to a Bihar-like drop in the EP Ratio in the entire country, we are looking at the potential disenfranchisement of about nine crore Indians.

As of now, we do not know where these “missing voters” are. Many of these could well be part of the 65 lakh names that are presumed by the ECI to be dead or away or untraceable. But our field experience confirms that a significant proportion of these “missing voters” are adult persons who live in Bihar and have not been included in the previous and current voters’ lists for one reason or another. Even if most of the deletions made by the ECI are genuine, the SIR failed to reach these adult residents who are eligible to vote. Oddly, for such a grand exercise of revision, the ECI has not reported a single case of addition. Clearly, the SIR was not an exercise in revision, but solely an exercise in deletion.

Needless to say, this evidence flies in the face of the Supreme Court’s call for “mass inclusion, not mass exclusion”. We wait to see how the court responds to the mounting evidence of under- and disenfranchisement due to the SIR.

Shastri and Yadav work with the national team of Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan. Yadav has filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging the SIR