Opinion Do freebies still win elections? Lessons from Bihar and Delhi

Freebies can bring about a marginal improvement and relief for the poor, but not a significant push for transforming the economic environment

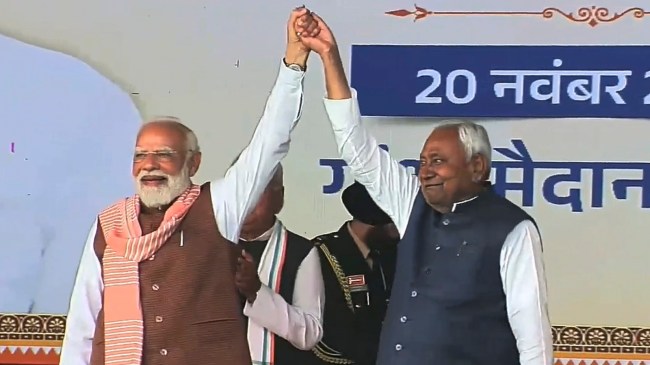

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with newly sworn-in Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar during the swearing-in ceremony, at Gandhi Maidan in Patna. (@Jduonline via PTI Photo/File)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with newly sworn-in Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar during the swearing-in ceremony, at Gandhi Maidan in Patna. (@Jduonline via PTI Photo/File) The strong pro-incumbency in Bihar and an anti-incumbency in Delhi in the same year have some common ground to reflect upon. Both elections were fought on the promise of targeted benefits. There may be a few local political and social issues that have influenced the results, but the impact of targeted benefits, also commonly referred to as political doles or freebies, cannot be overlooked. The strengths and weaknesses of targeted welfare measures vis-à-vis overall improvement of public goods and services should be understood not only from the perspective of electoral success but also from their long-term effects on the economy.

The NDA government introduced Rs 10,000 transfers to 1.21 crore prospective women entrepreneurs each just before the Model Code of Conduct was announced. A series of targeted and well-defined benefits were also announced during the past few months, including 125 MW free electricity, a hike in pension from Rs 400 to Rs 1,000 per month, Rs 1,000 monthly allowance for unemployed youth, Rs 5,000 one-time clothing allowance and a hike in the monthly honorarium of Jeevika, Anganwadi and ASHA workers. It appears that these measures were highly rewarding. Opposition parties have promised jobs for the youth, but these promises were not as reliable or well-defined as other targeted benefits.

Nevertheless, many of such targeted welfare measures did not appear to be electorally rewarding for AAP in Delhi. They promised Rs 2,100 per month to unemployed women and Rs 18,000 per month to Hindu and Sikh priests. Further, they promised financial assistance to Resident Welfare Associations and free healthcare for senior citizens. Although the party achieved prominence through its anti-corruption stance, its promises of free electricity and free water attracted especially the poorer sections of the city’s population. After assuming power in 2015, they improved the city’s education and health services by revamping government schools and establishing neighbourhood clinics (mohalla clinics). However, instead of more public goods, the list of freebies was lengthened later in their second term.

All these targeted welfare schemes are pro-poor, but there are marked differences in the manner in which they are relevant and accessible to different groups of citizens. Good schools and health facilities are public goods, and are important for all states, especially in Bihar, where one-third of the population is multi-dimensionally poor (considering health, education and standard of living), the highest in India. Why do political parties then find targeted welfare schemes more useful than public goods, when both have the potential to improve the welfare of beneficiaries? The former is more efficient for political parties as they can develop a patron-client relationship, known as political clientelism. While Nitish Kumar has developed such a clientele with the women of Bihar, AAP has developed such a clientele with Delhi’s poor, especially slum dwellers. Nevertheless, political clientelism undermines the provision of public goods. Political promises of public goods don’t seem to be effective in eliciting political support or votes.

Our study on the basic service provision in Kolkata slums reveals that political contestation, marked by high political competition (a narrow margin in the election) and high political fragmentation (many contestants), undermines the overall provision of basic public services. Further, considering changes in basic services over 10 years reveals, that in the backdrop of high political contestation, political actors do not put effort into improving a service (such as the duration of water supply) where no improvement was observed during the last decade, or where they failed to establish credibility. A lack of credibility encourages political clientelism and aggravates the quality of that service. However, high political contestation can lead to better services when political actors build or regain credibility.

As the experience shows, in the case of Bihar, the assurance of more jobs, let alone one job for each family, is not a credible promise. The percentage of regular formal workers aged 15 years and above has been persistently the lowest — ranging from 2.13 per cent to 3.23 per cent, between 2005-2022. Hence, even if it is the most important and desired economic change in Bihar, the promise of one job per family did not yield the desired returns for the Mahagathbandhan. On the contrary, the infrastructural development under Nitish Kumar’s tenure, along with a sharp reduction in multidimensional poverty (18.13 percentage points reduction of multidimentionally poor population between 2015-16 and 2019-21) and steady economic growth (3.5 times increase between 2011-12 and 2023-24), has improved Kumar’s credibility and provided electoral benefits amid high political contestation. Contrarily, the AAP’s credibility suffered due to deteriorating basic services, which had a more severe impact on the slums. This may have made their electoral fortune bleak.

Another issue is the economic condition of the masses, which might make conversion of votes against targeted welfare benefits easier or cheaper. Bihar’s per capita Net State Domestic Product was as low as Rs 53,478 in 2022-23, one-third of its all-India counterpart at Rs 1,71,822. So, it was easier to attract the poorest through targeted welfare benefits. In contrast, in Delhi, the upward mobility of the erstwhile poor voters may have made it difficult to convert votes through targeted benefits. There has been a reduction in inequality in urban areas in India. The National Sample Survey Organisation’s (NSSO) estimates reveal a sharp decline in the Gini coefficient of total consumption expenditure, from 0.363 in 2011-12 to 0.284 in 2023-24. It means many poor people are catching up with the middle class. Moreover, the average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) for residents of urban Delhi was 22 per cent higher than the national average. Economically prosperous voters value a better city over paltry benefits.

Direct welfare transfers are likely to be less attractive once the economic conditions of people cross a certain threshold. NSSO estimates that the difference between rural and urban monthly per capita consumption expenditure reduced from 83.9 per cent in 2011-12 to 69.7 per cent in 2023-24. If this trend of economic mobility continues alongside urbanisation, voters will likely reject freebie politics in the future.

Freebies can bring about a marginal improvement and relief for the poor, but not a significant push for transforming the economic environment. A more planned and scientific approach, along with credible promises, is required for India to become Vikshit Bharat by 2047.

The writer is professor and Axis Bank Chair, Institute of Rural Management Anand. Views are personal