Opinion Austen’s Jane is the friend you need

Elizabeth is the favourite of her dad, the intelligent, witty parent, while throughout the book, Jane is taking care of their mother, the petulant, embarrassing parent. While Elizabeth goes vacationing with her aunt and uncle, it is Jane who is best suited to “play with, teach, and love” their four small children.

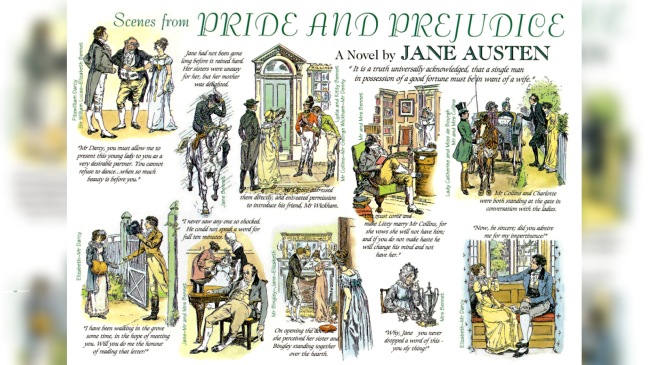

Scenes from Pride and Prejudice, by C. E. Brock (Wikimedia)

Scenes from Pride and Prejudice, by C. E. Brock (Wikimedia) It is a truth often ignored that the Pride and Prejudice screen adaptations are unfair to her secondary characters. As the 2005 movie returns to Indian cinemas and a new series hits Netflix, amid all the sizzle and dazzle of the lead pair, another generation of viewers will probably dismiss Jane Bennet as the sweet, boring sister of Elizabeth.

However, the eldest Miss Bennet was written with more substance than is universally acknowledged, and she would probably be a better friend than the clever Lizzy in today’s world.

One of the many reasons the charms of Pride and Prejudice refuse to fade is how easily the main story adapts to the screen. Jane Austen’s sparkling dialogue can directly be lifted into the screenplay, and the lead characters, Elizabeth and Mr Darcy, confirm to modern sensibilities. Written 200 years ago, Elizabeth has more spirit and verve than many 21st century heroines. The rich, brooding Mr Darcy is an atypical romance hero in that he actually understands consent.

In contrast, Jane Bennet’s rather unfashionable and non-camera-friendly virtues seem to be patience, forgiveness, and suffering in silence. In fact, most movies don’t even do her the justice of adhering to the one fact the novel hammers on, that Jane is much more beautiful than Elizabeth.

But the thing about the book Jane is this — she is not just beautiful and sweet, she is kind and strong, and has good judgement without the need to judge. Austen repeatedly alludes to Jane’s good sense, steady disposition, and moral courage. When the Bingleys are pressing her to stay on at Netherfield, Austen writes, “Jane was firm where she felt herself to be in the right.” When Lizzy says Jane can never see a fault in anybody, she replies, “I would not wish to be hasty in censuring anyone; but I always speak what I think”, which Elizabeth agrees is the case.

Elizabeth is the favourite of her dad, the intelligent, witty parent, while throughout the book, Jane is taking care of their mother, the petulant, embarrassing parent. While Elizabeth goes vacationing with her aunt and uncle, it is Jane who is best suited to “play with, teach, and love” their four small children.

And of course, it is Jane’s assessment of Mr Darcy that turns out to be the right one, after all.

One of the most telling commentaries on Jane’s character comes from Austen much later in the book, when Elizabeth tells her about Wickham’s true character. Jane would “willingly have gone through the world without believing that so much wickedness existed in the whole of mankind, as was here collected in one individual”.

And this is why I think she would make for a better friend than Lizzy in today’s world — choosing to believe in the goodness of the world and its inhabitants, in the face of staggering counter-evidence.

While their circumstances turn Elizabeth cynical, Jane continues to believe that romance and love and hope and goodness are around and even aplenty.

Also, Jane refuses to perform. Throughout the book, there is no scene of her being singled out to play or sing, or of some sparkling repartee she delivers. Her good sense and brains are all displayed in acts of care or confidence. Liz and Charlotte even discuss how she does not display her affection for Bingley.

In the hyper-performative age we live in, Jane’s willingness to forever pass the mic would be truly radical. At a time when we seem to live for likes and views, a stunningly beautiful woman who refused to play for attention is refreshing.

The sparkle of Lizzie Bennet will never fade. But it is the steady light of Jane we need when our hearts feel heavy and dark.

The writer is Senior Assistant Editor, The Indian Express