Saying It Like Mani

A witty and argumentative take on the numerous issues of our times

A time of transition: Rajiv Gandhi to the 21st Century

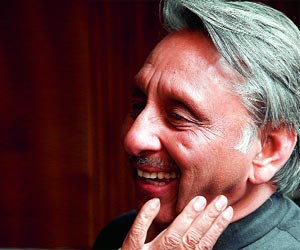

Mani Shankar Aiyar,

Penguin,The Indian Express,Rs 599

A witty and argumentative take on the numerous issues of our times

Although the title suggests a time of transition in Mani Shankar Aiyars political career,this book is more about his steadfast beliefsdemocracy,secularism,socialism and non-alignment than it is about the passage of time. A wonderful collection of columns,written for The Indian Express,from 1996 to 2004,this book provides a characteristically lucid,acerbic,witty,irreverent,self-deprecating,intelligently unfashionable,yet unashamedly partisan introduction to these concepts in action.

Aiyar has also been a tireless champion of the profound claim that Indian democracy needs to be deepened by making it more participatory. The excitement of this democracy is that millions now want to shape their own destiny,and we need decentralised participatory structures that can respond to this bubbling from below. Aiyars poignant introduction captures much of the clarity and excitement about this issue in Rajiv Gandhis own conception of democracy. It is such a pity that most of his party,and most of the custodians of government,do not understand what is at stake in decentralisation. And they would do well to re learn what Rajiv Gandhi had in mind.

Aiyar is,however far less convincing on his other two themes: socialism and secularism. Socialism,as lived doctrine,rather than a set of values is always marked by a touch of hypocritical chicanery. Aiyar does have a cogent defence of the idea that the state does need to do a lot of things. But in this day and age to write about socialism without reflecting at all on the failures of Indian statism and its corruption into a self-defeating populism is a bit odd. But in some ways Aiyar ought to be more wary of socialism,precisely because he is such a compelling democrat. What stands out in his democratic credentials is the powerful strand of anti-paternalism: it is simply wrong for higher levels of government to take decisions that should be taken through participation. But it is precisely this fear of paternalism that leads liberals to be suspicious of overweening state power.

The very state that says that it alone will decide what is to be produced by industry or how much,what is to be taught in our universities,will also be the state that will distrust the peoples capacity to choose wisely. Liberals and decentralisers have actually more in common than Aiyar acknowledges,and he fails to consider the possibility that it is precisely statism that came in the way of empowering people.

On secularism he is less convincing for a different reason. His attacks on the BJP and many woolly-minded colleagues in his own party are spot-on. His own values are cogently defensible and ones to which sensible constitutionalists should subscribe. But on this topic,his characteristic powers of self-reflection are less evident. Secularism becomes so much a slogan for partisan politics that it skirts some of the more difficult questions. Why did the Hindutva become such a genuinely powerful social movement? Simply assigning blame to Advanis yatras is not enough. A more brutally political way of putting this question would be this. Even when Congress has everything going for it,why does it leave the country divided and state institutions corrupted and weak? It can be said of Aiyar what was said of Burke: he gave to party what was meant for mankind. One can only hope this brilliance will return to its larger purpose.