Reporting is perilous trade under army rule

When a Pakistani Brigadier General invited journalist Aziz Sanghur for tea in the summer of 2002, all Sanghur had expected was tea. Instead,...

When a Pakistani Brigadier General invited journalist Aziz Sanghur for tea in the summer of 2002, all Sanghur had expected was tea. Instead, the brigadier8217;s aides served Sanghur an hour-long beating 8212; for his coverage of protests against blackouts at Karachi8217;s municipal electric company, which is run by the military. The brigadier was the MD.

When Sanghur tried to press charges against the officers for the attack, the police told him he had no 8216;8216;right to file a complaint against a serving brigadier8217;8217;. This August 2002 assault, says Sanghur, highlights a problem for the press in the strategically sensitive country: News bodies are vigorous and independent, but confront political lines that are hard to see and dangerous.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan recorded more than 50 cases of violence and harassment against journalists last year.

Sultan Ahmed, spokesman for the Karachi Electrical Supply Corp, however, denied that Sanghur was beaten and called the incident 8216;8216;totally concocted8217;8217;.

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists had in its recent summary on Pakistan said that harassment by state intelligence agencies and other pressures 8216;8216;have intensified under Musharraf8217;s rule8217;8217;. Pakistan had recently restricted the movements of foreign journalists. Although reporters for years have needed permits to enter the semi-autonomous 8216;8216;tribal zones8217;8217; along the Afghan border, the government recently expanded the restricted area to include Quetta and Peshawar.

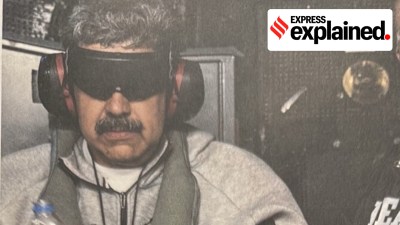

Early this month, Pakistani courts convicted two French journalists of travelling to Quetta without a permit. The two, a reporter and a photographer for the Paris weekly L8217;Express, were allowed to return to France last week, but a Pakistani journalist working with them, Khawar Mehdi Rizvi, is still in custody. 8216;8216;The investigation is on in his case,8217;8217; said Information Minister Sheikh Rashid Ahmed.

Last month, Musharraf had voiced frustration with news media, asking 8216;8216;why does the press consider it a comedown to lend sincere support to the government?8217;8217; Pakistan8217;s press is boisterous, sometimes satirical, and includes publications that regularly challenge government policy. At the same time, media faces attack or imprisonment if they write too critically of the army or if they nose too close to issues such as Pakistan8217;s nuclear program, drug trade, intelligence agencies or Islamic militant groups.

Journalists are frequently offered 8216;8216;handsome money8217;8217; to turn away from such controversial topics, says Mazhar Abbas, Pakistan bureau chief for Agence France-Presse, and head of Karachi Union of Journalists. If that doesn8217;t work, 8216;8216;police will threaten you, say you are against the national interest.8217;8217; 8212; LAT-WP

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05