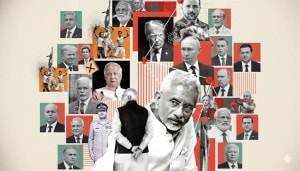

Pinning General to specifics

As the foreign secretaries of India and Pakistan begin third round of dialogue next week, a political paradox confronts the peace process. F...

As the foreign secretaries of India and Pakistan begin third round of dialogue next week, a political paradox confronts the peace process. For Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and President Pervez Musharraf, these are the best of times and the worst. Together they have engineered more positive outcomes in Indo-Pak relations during the last 18 months than in the previous four decades. Yet a frustration in both capitals has begun to envelop the peace process.

Musharraf8217;s remarks to a television channel captured the mood. India and Pakistan 8216;8216;never had it so good8217;8217;, Musharraf said. And yet, he added, 8216;8216;a degree of disappointment is gradually setting in me8217;8217;. Musharraf is absolutely right on the first count. On the second, he is not the only one disappointed; so is Manmohan Singh. If Musharraf is chafing at the lack of progress on Kashmir, the PM is angry at the renewed terrorist attacks in Delhi, Srinagar and Bangalore.

On the positive side of the ledger, the list is long. Yet another cricket series between the two is upon us8212;the third in barely two years. More people are travelling between the two nations. More transport links are being revived. Track two seminars and mushairas are in full swing. Visas are still difficult to get; but the situation is not quite as bad as it used to be. Even the Hurriyat leaders are being allowed to travel to Pakistan if only to say things that General Musharraf loves to hear. Trade between the two countries is booming. The Confederation of Indian Industry tells us that during the first eight months of 2005-06 trade has grown at a whopping 76 per cent. Two-way trade could reach a billion dollars by March 2006.

On the military front, a ceasefire all along the international border, Line of Control in Kashmir and Siachen has held for more than two years. Delhi and Islamabad are moving forward on nuclear confidence-building measures8212;including an agreement on pre-notification of ballistic missile testing and a mechanism for nuclear risk reduction. Despite the progress across a broad front, there is a growing sense that the peace process might yet be reversible. The reasons are three: the central political premise of the negotiation has become shaky; Musharraf8217;s diplomatic style is hurting the process; and substantive proposals have been undermined by sloganeering.

Unraveling bargain

The first is that the political bargain that allowed Musharraf and Atal Behari Vajpayee to launch the peace process in January 2004 has come under great stress. The essence of that bargain was that Pakistan would end cross-border terrorism and India would negotiate purposefully on Jammu and Kashmir. After two rounds of dialogue, Musharraf feels India is dragging its feet on Kashmir and India is convinced that Musharraf is not prepared to keep his word on cross-border terrorism. The two sides also agreed that as they talked Kashmir in an environment free of violence, confidence-building measures across the board should be implemented. While considerable progress has been demonstrated on the CBM front, levels of violence have not come down and Kashmir talks are yet to acquire traction. From the very beginning the linkage between terrorism and Kashmir talks was the key to a successful peace process. Pakistan feared that India would not negotiate without a gun pointed at its head. India was never convinced that Musharraf will remove the gun. Unless both sides offer reassurances to each other8212;India will negotiate seriously on Kashmir and Pakistan will crack down on terrorism8212;the peace process is bound to stall.

Musharraf8217;s style

Mutual trust is the key component of any successful negotiation. Musharraf is now in anger of losing his credibility in New Delhi as a serious interlocutor. Just hours before meeting the Prime Minister in New York last September, Musharraf repeated all the cliches on Kashmir and UN resolutions at the General Assembly. His promises to deliver results on cross-border terrorism have not been kept. Worse still, Musharraf appears to be under the impression that India could be hustled into concessions by publicly putting pressure on New Delhi. His campaign to get India accept his proposals on 8216;8216;self-governance8217;8217; and 8216;8216;demilitarisation8217;8217; for Kashmir has had the opposite effect on India. India has offered to discuss any proposals on Kashmir that Islamabad puts forward. Until now it is India that has put new ideas for cooperation on Kashmir; while Musharraf talks big on Kashmir in his media interviews, his negotiators have offered little of substance in the formal talks.

Self-governance and demilitarisation

The good news is that Musharraf, in coining the new slogans on 8216;8216;self-governance8217;8217; and 8216;8216;demilitarisation8217;8217; has moved considerably from his old slogans on 8216;8216;self-determination8217;8217; and 8216;8216;plebiscite8217;8217; to something between independence and autonomy. But the bad news is that Delhi is not sure if he is not devious. The best way of finding out is to test Musharraf by making counter-proposals on Kashmir. India should have little problem talking about 8216;8216;self-governance8217;8217; and 8216;8216;force reductions8217;8217; on both sides. Rather than dismiss Musharraf8217;s proposals aired through the media, India should try to explore Musharraf8217;s bottom line on 8216;8216;self-governance8217;8217; and 8216;8216;demilitarisation8217;8217;.

For all of Pakistan8217;s pretence that the areas under its control in J038;K are independent, they are administered directly by the Federal Government in Islamabad through the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas. On 8216;8216;demilitarisation8217;8217;, India should explore the possibilities for unilaterally modifying its military disposition in Jammu and Kashmir as part of its political engagement with the Kashmiri groups. After all size of the security forces is only one determinant of the security condition in Kashmir.

The challenge for Indian diplomacy in the next round of peace process is two-fold8212;offer a genuine way forward on J038;K while simultaneously exposing, publicly, the contradictions of Pakistan8217;s Kashmir policy.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05