Looking past the stereotypes and accepting Urdu as the sum of its parts — its sounds and script

It may have shrunk in importance but it’s still part of our daily lives. So, can we look past the stereotypes and accept Urdu as the sum of its parts: its poetry and politics, its sounds and script?

A still from Ghalib, in which Tom Alter plays the Urdu poet.

A still from Ghalib, in which Tom Alter plays the Urdu poet.

IN this winter of discontent, let me bring you some good cheer. On a recent trip to Allahabad, meeting people young and old, educated and not so, it was heartening to hear robust spoken Urdu. Young and vivacious Aayushi Sinha, who has recently completed her Masters in English, spoke to me in immaculate conversational Urdu, bol-chaal ki zubaan, as she showed me around her historic campus. Lalit Joshi, Professor in the Department of History, spoke about cinema and the arts in a shusta zubaan, a language so chaste that it would put any Urdu scholar to shame. The driver who drove me around, with a wad of tobacco firmly tucked in one cheek, spoke in a sweetly lyrical purabiya-inflected flavorsome and idiomatic zubaan redolent with the fragrance of the Gangetic plains. With the possible exception of Prof Joshi, the others may or may not have given any particular thought to the linguistic niceties of what was, after all, for them their most natural mode of communication.

A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet, the Bard had told us. And so it is with Urdu. Call it Urdu, Rekhta or Hindustani, its spoken register remains much the same. And it is used by large numbers of people across South Asia — as well as equally large numbers of people from the Indian diaspora who live in different parts of the world and have managed to keep their spoken language relatively intact with a healthy vocabulary and vigorous idiom. In fact, Javed Akhtar, the poet and lyricist captures the nub of the argument when he says only half-jokingly, ‘Jab tak aapko meri baat samajh mein aa rahi hai main Hindustani mein bol raha hoon; jab aapko meri baat samajh mein nahi aane lagti hai aapko lagta hai mein Urdu mein bol raha hoon!’ (‘Till you can understand what I am saying, it would seem that I am speaking in Hindustani; but when you can no longer follow what I am saying you think I am speaking in Urdu!’). Urdu, for many, is about the limitations of vocabulary since syntax and grammar are similar to Hindi.

Indeed many of us use Urdu instinctively, almost organically. We know, for instance, that Urdu comes to the aid of many a lover wanting to express undying love for the beloved; a random search on the internet will throw up phenomenally large numbers of Urdu verses — good, bad, indifferent — to convey the many moods and moments ranging from visaal (union) to firaaq (separation), and from ishq-e haqiqi (divine love) to ishq-e majazi (worldly love). But then Urdu catches us unawares in other guises too. For instance, when agitationists both north and south of the Vindhyas — be they University teachers or factory workers — declare ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ (‘Long Live the Revolution!’), they are simply echoing the cry of Hasrat Mohani, the maverick Urdu poet who wrote sweetly lyrical ghazals in the chastest metre such as ‘Chupke chupke raat din ansu bahana yaad hai’ (‘I remember the silent tears you shed day and night’) and also invoked this revolutionary slogan at a factory workers’ rally in Calcutta in December 1925. Finance Ministers over the years, with the exception of the present incumbent, have presented the Budget replete with the choicest Urdu verses to express emotions ranging from ingenuity to plain helplessness. Surprisingly enough, even the Honourable Prime Minister Modi, no known lover of Urdu, sought refuge in a verse by Nida Fazli when he found himself beleagured on the floor of the House and wanted to reach out to his fellow Parliamentarians:

Safar mein dhoop to hogi jo chal sako to chalo,

Sabhi hain bheed mein tum bhi nikal sako to chalo,

Kisi ke vaaste raahein kahaan badalati hain,

Tum apne aap ko khud hi badal sako to chalo,

The sun will be strong on this journey, come with me if you can

Everyone is jostling in this crowd, if you can get ahead come

The turns of the road don’t change for anyone

If you can change yourself, come with me if you can

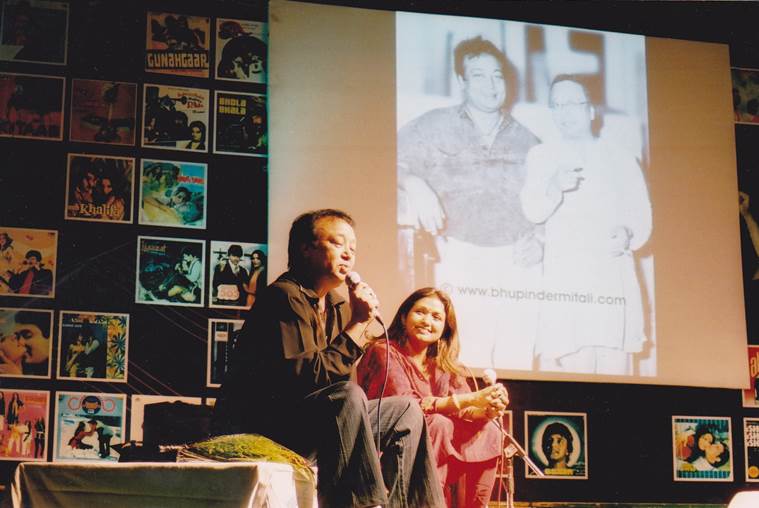

Ghazal singers Bhupinder and Mitalee Singh.

Ghazal singers Bhupinder and Mitalee Singh.

So far so good. Having established that Urdu is very much a part of our lives and daily rhythms in different ways and degrees and is neither dead nor dying, let us look towards the future. Let us make no bones: Urdu has shrunk in importance yes; it is no longer the lingua franca it was till the 1940s. Urdu is not linked to employment opportunities save some in cinema or the media or teaching — with the exception of Bihar where jobs are ear-marked from the block level upwards in government employment for those who come from the Urdu medium — it would not be wrong to say that spoken Urdu is still in currency. But what of the script? For it is the script, after all, that has always evoked the ire of the hyper-nationalists stirring in their nationalist breasts a peculiar mixture of rage and hostility. So what does the future hold for the script, the rasm-ul khat? Can we splice a language from its script and expect it to flourish? It is here that I have some misgivings and its is here that the situation reveals itself as being tashweeshnaak, a real cause for worry.

For far too long Urdu has been bedevilled by the bogey of its script being alien, derived as it is from the farsi rasm-ul khat and its alphabet being similar, though not identical, to Arabic and Persian. This coupled with the other bugbear — that Urdu is the language of Muslims — has been used to browbeat and marginalise written Urdu in the seven decades since Independence. As a result, today fewer and fewer people access Urdu through its script; the great many ether rely on audio sources (Urdu sher-o-shayari being the greatest saviour of the Urdu zubaan) or access Urdu texts through Roman or Devnagri.

Like a nadaan dost, an unthinking friend, even its well-wishers adopt a form of benign patriarchy when it comes to the matter of script suggesting that since Urdu can be read in Devnagri why not do away with the rasm-ul khat altogether? Why not make Urdu literature available to modern readers through Devnagri transliterations or English translations? Why bother to learn the script since it is so ‘difficult’? My answer to that is all scripts are difficult till they become known and therefore easy. After all, someone held our hand and taught us to trace the A, B, C and the Ka, Kha, Ga; so why not learn the Aleph, Be, Pe even though it seems difficult at first? Why burden Devnagri with sounds such the guttural Qaaf or the Khhe that it was never meant to carry? Why not look past the terrible stereotypes and closed mindsets to access a language and its literary culture in its entirety? Why not accept Urdu as the sum of its parts: its poetry and its politics, its sounds and its script? And, what is more, why not adopt an approach that is de hors state sponsorship, something along the lines of an ‘Each One Teach One’?

Till such a mindset prevails we will have fewer reasons to be entirely sanguine about the future of Urdu.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05