A TEAM of researchers from the Bengaluru-based National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) and the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) has found that the Indian elephant migrated from the north to the south over many millennia and lost their genetic diversity progressively with each southward migration.

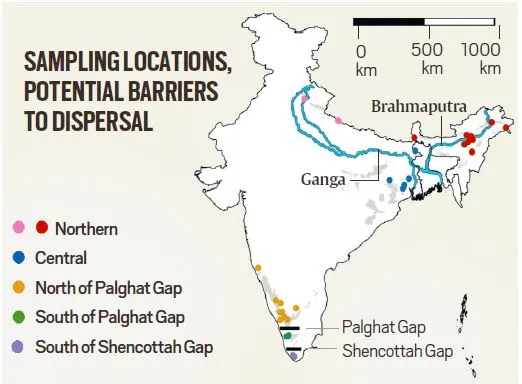

Published in the latest issue of Current Biology, the study analysed whole genome sequences from captive and wild elephant blood samples collected across India to identify five genetically distinct populations — one along the Himalayan foothills from the northwest to northeast, one in central India, and three in the south.

According to the last national census conducted in 2017, India is home to more than 29,000 elephants. While the three southern populations added up to 14,500 elephants, the central population was estimated at over 3,000. The northern population accounted for the remaining 12,000 — around 2,000 in the northwest and 10,000 in the northeast.

As evidence for Indian elephants migrating from the north to the south, the study — titled ‘Divergence and serial colonization shape genetic variation and define conservation units in Asian elephants’ — found that the northern elephant population diverged from all other Indian populations more than 70,000 years ago.

Indicating further southward dispersals over time, the central Indian elephants diverged from the rest more than 50,000 years ago and the divergence among the three southern populations dated back to only around 20,000 years.

The study underlined that India’s southernmost population, found south of the Shencottah Gap that connects Tamil Nadu and Kerala, has the lowest genetic diversity.

The study underlined that India’s southernmost population, found south of the Shencottah Gap that connects Tamil Nadu and Kerala, has the lowest genetic diversity.

As a result, explained Anubhab Khan, the study’s lead author now with the IISc, Bangalore, the reduced genetic variation in the southern populations is possibly a manifestation of the serial founder effect, where fewer individuals from one population migrate to establish new populations and so on.

“As these populations become smaller, the risk of inbreeding depression increases—a phenomenon where harmful genetic variants are more likely to be inherited due to breeding among related individuals,” Dr Khan said.

Story continues below this ad

Aimed at identifying key populations that need tailored conservation strategies, the study underlined that India’s southernmost population, found south of the Shencottah Gap that connects Tamil Nadu and Kerala, has the lowest genetic diversity. “This small isolated population of fewer than 150 elephants is potentially the most vulnerable to risks of extinction,” said Professor Uma Ramakrishnan, one of the authors of the study from the NCBS, Bangalore.

Until now, the southern elephant population was believed to be divided by the Palghat Gap which acted as a natural barrier to elephant dispersal along the Western Ghats. Offering new insights, the study has revealed that the Shencottah Gap further south also acted as an impediment to elephant movement, resulting in three genetically distinct southern populations — one north of Palghat, a second between Palghat and Shencottah, and a third south of Shencottah.

The study also confirmed two elephant populations identified earlier. While the central Indian elephants (found between south-western West Bengal and eastern Maharashtra) formed the fourth genetically distinct population, the elephants in the Northwest (Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh) and Northeast India — largely separated from the rest of India by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers — constituted the fifth population.

Running west to east along the Himalayan foothills, the north Indian elephant landscape extends from Uttarakhand to Arunachal Pradesh. Though the connectivity between elephant habitats scattered in this landscape is now disrupted at many places, genetic evidence suggests that elephants lived here as one population for a long time since the ancestors of present-day Asian elephants moved from the plains of Africa into Eurasia and finally to Asia.

Story continues below this ad

Underlining the urgency for maintaining habitat connectivity, Prof Ramakrishnan pointed out that recent infrastructure development might have further reduced gene flow among the three populations in the Western Ghats.

“The identification of these five genetically distinct populations underscores the need for region-specific conservation efforts,” she said, adding that the research team plans to develop a genetic toolkit, based on DNA extracted from elephant faeces, to help monitor populations more accurately and identify individual elephants in the wild.

The study underlined that India’s southernmost population, found south of the Shencottah Gap that connects Tamil Nadu and Kerala, has the lowest genetic diversity.

The study underlined that India’s southernmost population, found south of the Shencottah Gap that connects Tamil Nadu and Kerala, has the lowest genetic diversity.