D Subbarao at Idea Exchange: ‘Democracy functions best if there is sufficient space for Opposition’

Hardly had D Subbarao taken charge as the Governor of the RBI on September 5, 2008, that the Lehman Brothers collapsed in the US, triggering a global financial crisis which quickly spilled over to the real economy.

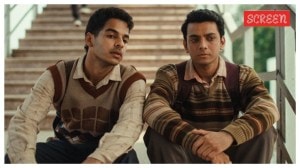

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)Economist and former central banker D Subbarao on how the RBI has dealt with multiple crises, internationalisation of the rupee and why corporates are not investing yet. This session was moderated by Ishan Bakshi, Associate Editor, The Indian Express

Ishan Bakshi: The Indian economy has seen two major shocks in the past two decades: the financial crisis of 2008 and the Covid pandemic. What are your views on the policy response of the then and now government and RBI?

Let’s first talk about the two crises and their origins. We had the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, and then we had the financial crisis triggered as a consequence of the pandemic. The GFC had its origins in the financial sector, whereas the financial disruption that happened following Covid was a result of a cause outside the financial sector. When the GFC happened, central bankers and governments were in the forefront because the solution had to come from within the financial sector.

In the financial crisis after Covid, the solution had to come from outside the financial sector. You are right in the sense that both governments and central banks played from the same playbook in terms of responses to the financial instability. But, as I said, there is a difference because central banks were doing a holding operation during and after the pandemic, until a solution came, whereas in the GFC you were there right in the centre and front, fighting it. In the GFC, America was the epicentre. Whereas, after the pandemic you had to ensure that there was no pandemic anywhere in the country. In terms of effectiveness, at least in managing the financial fallout of the Covid pandemic in India, both the government and the RBI have done very well.

Ishan Bakshi: Do you think the central bank should be actively intervening in currency markets?

No, if anything, the RBI should be less interventionist than it is. I say this because we want to be a developed economy, we want financial deepening, we want more capital to come in. So we need more exchange rate flexibility instead of an expectation in the market that every time the exchange rate moves, the RBI intervenes. If the RBI intervenes, let’s say, to prevent appreciation, it is building reserves, but there are costs to holding reserves. Unlike China, whose reserves are built out of their earnings, our reserves are built out of borrowing.

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

The second reservation I have about RBI’s intervention is that you’re shifting the burden of adjustment from one segment in the economy to another. Again, illustratively, if the RBI is preventing appreciation of the rupee, it is benefitting exporters at the cost of importers. Is that fair?

On RBI-government tussles: Tension between govts and central banks is in some sense hardwired into the system… As the central bank tries to maintain price stability and financial stability, short-term goals might be compromised

Third, if the RBI’s stated policy is that we do not target an exchange rate, we only manage volatility and if the RBI is seen intervening even if there is no apparent volatility, the market will tend to believe that the RBI is targeting an exchange rate.

My most important reservation about this policy is that when the RBI intervenes, there is a moral hazard. If you want to be a developed economy, you want our market participants, corporates to be able to manage the exchange rate risk. If the RBI keeps intervening, they will outsource risk management to the RBI, which has a cost.

Finally, on the 90th anniversary of the RBI, the Prime Minister had said that the RBI must try and internationalise the rupee. That’s not going to be possible if the RBI continues to intervene.

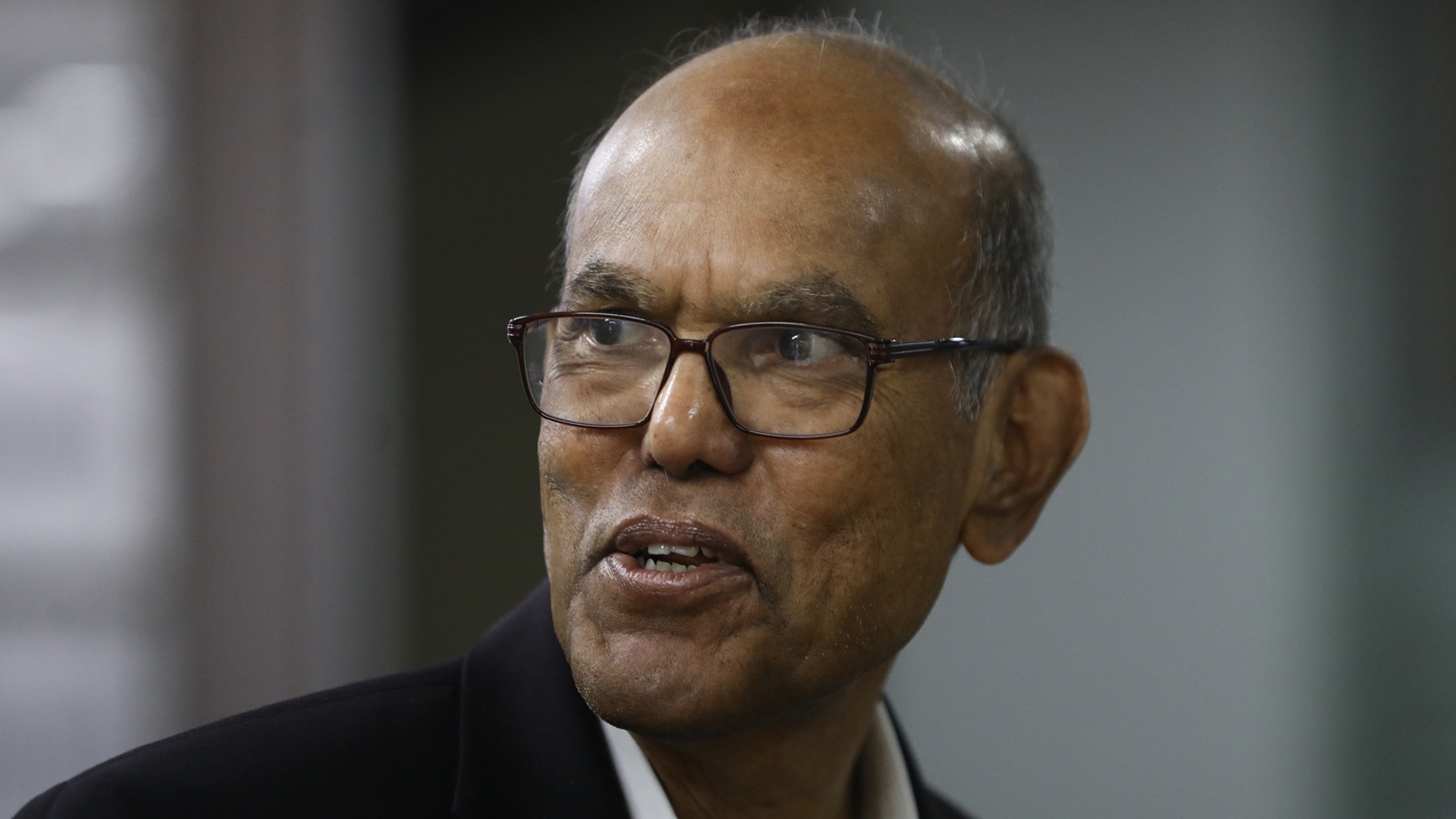

Economist D Subbarao

Economist D Subbarao

Harish Damodaran: You have talked about too much fiscal stimulus during the UPA period and the stimulus not being withdrawn.

One is fiscal stimulus, second is the monetary stimulus, but there was a third stimulus which was too much credit and that created a legacy problem of twin balance sheets. They have now come out with draft regulations on project-lending, but was that the real problem?

I must admit that the monetary stimulus we had given during the crisis was not withdrawn soon enough. And that was for reasons… I admitted that the economy would have been served better had I withdrawn the monetary stimulus faster. But we were acting in real time within the universe of knowledge available to us. The information we were getting was that the economy had not picked up. Only in hindsight we realised that growth was in fact faster. If you throw back your mind to that time, there was a lot of concern about financial instability. The global financial crisis had not died. In hindsight, the credit flow, particularly to the infrastructure sector, was much more than what would have been healthy for the economy. But again, we were acting in real time. Infrastructure was uncharted territory, both for the corporates investing in infrastructure and for banks lending to them. Other factors that came into play included the Supreme Court orders cancelling coal blocks, cancelling 2G ban on exports, which affected the quality of credit, quality of recovery and growth.

On Fiscal management: The economy would have been served better if I had withdrawn the monetary stimulus faster… In hindsight, the credit flow, particularly to the infrastructure sector, was more than what was healthy for the economy

Ravi Dutta Mishra: In your book Who Moved my Interest Rate? (Penguin) you mentioned that it was not the financial crisis that bothered you more but the currency depreciation that followed. How do you compare that period and now, the volatility and the management?

The management was better this time. I don’t want to be defensive but that was a different problem as compared to today. The taper tantrums happened because of a lot of quantitative easing that money had flowed in. Then (Federal Reserve) chairman (Ben) Bernanke said they were going to taper and emerging economies lost stability, our exchange rate dived 20 per cent peak to trough in a matter of four months. We were part of the fragile five because of structural problems in our economies, not just the exchange rate… The fiscal deficit we were running, the quality of our imports, high oil prices and so on.

We learnt from that lesson but this time the exchange rate had moved. The flows that had come had not exceeded suddenly, so there was not that sudden stop and reversal as we had seen that time. It was relatively easier to manage the exchange rate this time. Apart from that, we have a war chest of reserves, our fiscal deficit is much lower, our fiscal credibility is higher.

Economist D Subbarao

Economist D Subbarao

Sukalp Sharma: Do you think the internationalisation of the rupee can be achieved in near-to-medium term or is it wishful thinking?

It certainly cannot be achieved in the short term. Whether it’s achieved in medium-term or long-term, I do not know. But it’s feasible. The US dollar is the world’s dominant reserve currency today not because countries got together and anointed the US dollar as the reserve currency but because of the strength of the American economy, depth and resilience of the American financial markets, and credibility of American institutions of governance.

For India, it is good for our trade and investment. But if two trading partners have to do their trade in their bilateral currencies, the trade has to be roughly balanced. For example, between India and Bangladesh, they pay us in taka, we pay in rupees, let’s say Bangladesh builds up huge balances and they say, ‘What do we do with the rupee, pay us in dollars’. So if a trade is roughly balanced, it’s possible to internationalise the rupee, but if there is a large trade imbalance one way or the other, it would be challenging.

Sukalp Sharma: Since 2014 — when we had a majority government for the first time in decades — two central bankers have left amidst voices of erosion of autonomy. During such periods, when we have a majority government, do you think central banks can be politics-proof?

Tension between governments and central banks is in some sense hardwired into the system. The core mandate of a central bank is to maintain price stability and financial stability. Delivering on this core mandate enjoins the central bank to keep long-term sustainability of the economy. Typically, there is a conflict between short-term compulsions and long-term sustainability. Because there is a conflict, institutionally, we have established a central bank at an arm’s length from the government. It acts independent of political compulsions. You cannot give the control of the printing press to governments because driven by short election cycles, political compulsions, they would misuse that. That’s why you have a central bank with a certain amount of autonomy. That is the institutional rationale for central banks, and that is why there is tension because as the central bank tries to maintain price stability and financial stability, certain short-term goals might be compromised.

During my time, growth was trending down, inflation remained stubborn and the growth inflation conflict was quite tense. Today, growth is doing reasonably well, inflation is above target but within reasonable range. So, the tension is not very strong. It is also a function of the chemistry between the Governor and Finance Minister and the Prime Minister.

On manufacturing versus the service sector: Manufacturing and service are not mutually exclusive. We have a huge unemployment problem. Numbers can be disputed but the problem cannot be denied

Ishan Bakshi: During this electoral cycle, there has been a reference to the issue of inequality and redistribution. There has been some advocacy of an inheritance tax. What are your thoughts on that?

I’m not competent to comment on that because I have not studied it. We certainly have a problem of inequality. (Economist) Thomas Piketty and others have done studies and there are several other world inequality indexes which show that India is one of the most unequal societies in the world. Resolving inequality is not just a moral issue or political issue. It is also an economic issue. We need to resolve inequality for our own long-term economic interest.

Our biggest growth driver is the consumption of the bottom segments of the population. If their incomes go up, they’ll spend that money. Their marginal propensity to consume is higher. If they spend that money, there will be more production, more jobs, more growth and we can get on to a virtuous cycle. If, on the other hand, the benefits of growth do not go to them, we cannot sustain our current growth momentum.

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Harish Damodaran: Why do you think corporates are not investing yet?

For about seven to eight years, we’ve had the NPA (Non-Performing Assets) problem, twin balance sheet problems. That is now behind us. Both corporate balance sheets and bank balance sheets are cleaned up. They are in the pink of health… The economy is running on a single engine now, which is public investment… If you look at capacity utilisation, it’s been low. It’s picking up. I think it’s 75 or 76 per cent now, and historically corporates have thought about investment when capacity utilisation gets to about 80 per cent. They must also be waiting for the election to get over.

Economist D Subbarao

Economist D Subbarao

Ravi Dutta Mishra: You mentioned the relationship between the RBI and the government is sometimes ruled by political considerations. In that context, how do you see the RBI’s dividends that it is giving to the government?

That’s a tricky question because I was on both sides of that battle. When I was finance secretary, I was resisting pressure from the RBI to pay higher dividend and as governor, I was resisting pressure from the government to pay higher dividend.

I don’t think that is a policy issue like monetary policy or regulatory policy. That is more of a fiscal issue. It is legitimate, appropriate for the government to ask for more money and for the RBI to make sure that its balance sheet is robust enough to command credibility because the central bank balance sheet is an important variable in potential investors assessing our economy. When does the IMF (International Monetary Fund) come into play? Typically when the government balance sheet is weak, they draw confidence from the fact that the central bank balance sheet is strong. After much thought, you should work on the central bank balance sheet. You should not do it light-heartedly.

It’s right for the government to ask for more, but the RBI wants to put it into reserves for covering their losses. The Bimal Jalan Committee has determined what is the level of reserves that the RBI must hold. I hope that formula will see that the friction on dividend payment is lower.

Economist D Subbarao

Economist D Subbarao

Ishan Bakshi: This government has made a concerted attempt, like previous governments, to encourage manufacturing. There has been a lot of debate on manufacturing versus service. Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan also advocated a more service-oriented pathway as opposed to manufacturing because the view is that we may have already missed the bus for manufacturing. What is your view?

Let me preface by what Dr Rajan and Rohit Lamba, his co-author, have said (in Breaking the Mould). To paraphrase what they’ve said, India is spending public resources in subsidising manufacturing, the hardcore of manufacturing. But if you take the entire chain of manufacturing, that is the least value-added segment. If the argument is that this is the entry point for the entire vertical chain to come to you, perhaps that expectation may not be realised because the comparative advantage of global value chains itself is getting eroded. In any case, India is a high tariff regime, so it is not worthwhile for the value chains to come in. On the other hand, as populations are ageing in rich countries, the demand will be more for services than for manufacturing. Because of technology, we are now able to deliver service from a distance. We have a first-mover advantage that we must exploit. That is the argument of this book. I agree with that.

But I do not think that is a solution to our short-term or medium-term problem. First of all, manufacturing and service are not mutually exclusive. Even Dr Rajan and Dr Lamba have not said that they are mutually exclusive. We have a huge unemployment problem. Numbers can be disputed but the problem cannot be denied.

We need to provide jobs in the semi-skilled segment. We need to focus on future generations, give them more skills and more education. But for the next five to 10 years, we need to provide jobs to this segment of labour force which is largely semi-skilled. The only way to do that is in the manufacturing sector.

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Economist D Subbarao (right) with Ishan Bakshi during the interaction (Express photo by Abhinav Saha)

Ishan Bakshi: Many have described this election as a make-or-break election. At the end of the day, what gives you hope, what worries you, what scares you and what are your expectations?

What gives me hope is the resilience of our democracy. What is of concern is the deeper problems that we have. As much as poverty has gone down, awareness levels, literacy levels have gone up and people now have a better quality of life than they did 25 years ago, there is still a lot of inequality and unemployment. My deeper worry is about the long-term challenges, which includes climate change. What are Artificial Intelligence and robotics going to do to comparative advantage? How are the geopolitics going to unfold? How will globalisation unfold? How in this world are different demographic transitions taking place that are going to change demand patterns and comparative advantages? How is India going to navigate through that? That’s a long list of my worries.

Ishan Bakshi: Does the shrinking Opposition space worry you?

I think democracy functions best if there is sufficient space for the Opposition.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05