Fatty liver at just 14: How junk food, hidden genes and obesity pushed teen to a liver transplant

Address childhood obesity and diet, urge hepatologists as fatty liver, once an adult disease, is now affecting teenagers

A series of investigations revealed multiple genetic mutations that explained the rapid deterioration.

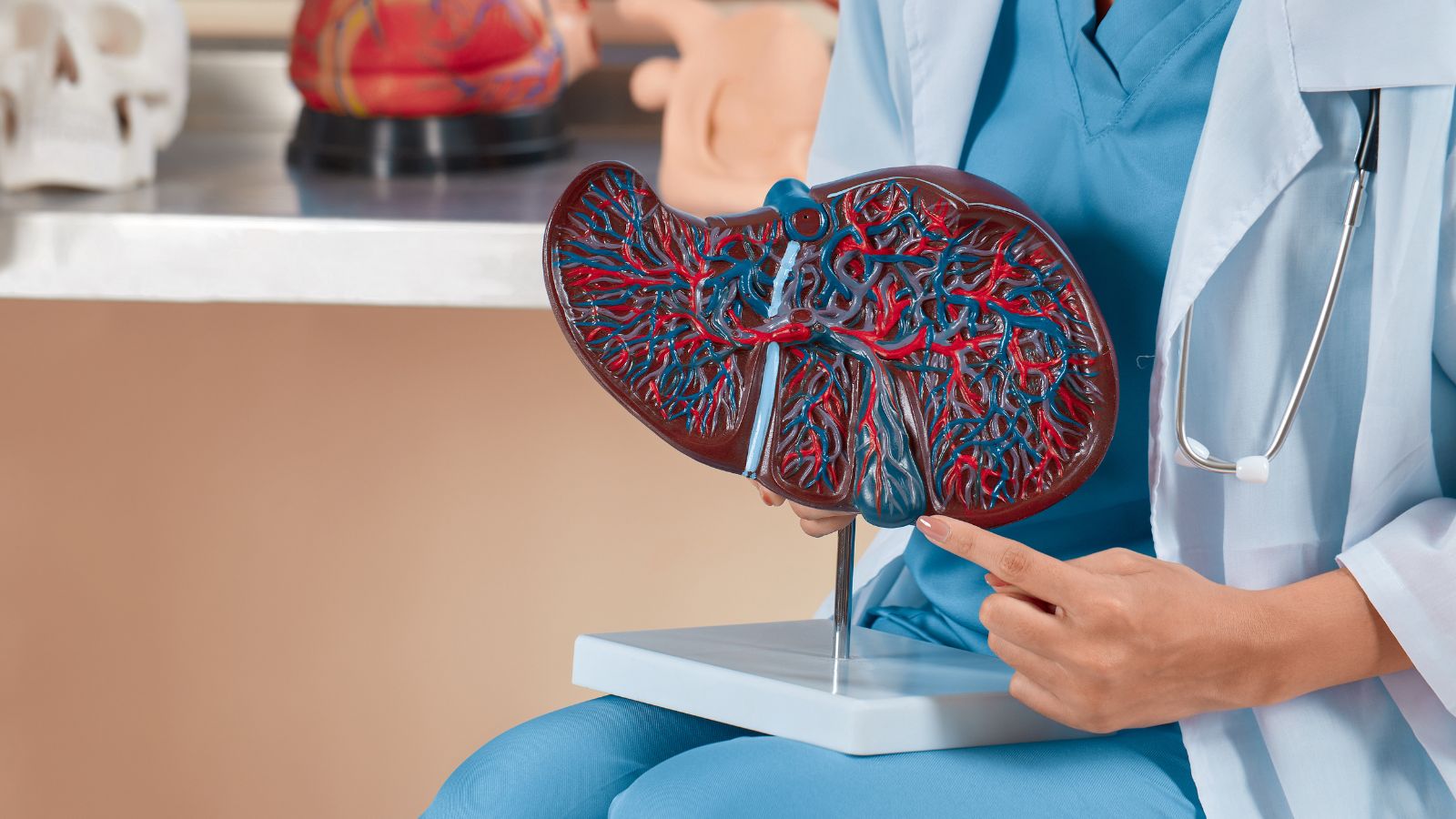

A series of investigations revealed multiple genetic mutations that explained the rapid deterioration.Fatty liver in teens may seem rare. Except it isn’t. It is now the most frequent cause of chronic liver disease, affecting an estimated 10–17 percent of adolescents with obesity. What remains rare, however, is the need for a liver transplant in a child under 18. That was the life-saving intervention for a 14-year-old boy from Surat, who arrived at Mumbai’s Sir H. N. Reliance Foundation Hospital with acute liver failure caused by an advanced form of fatty liver disease.

His case is a stark reminder of why childhood obesity demands urgent attention, especially in Indians who are genetically predisposed to fatty liver disease, even with only abdominal fat.

The teen is now recovering at home, with all parameters holding steady as he underwent a liver transplant just a month ago. His father stepped in as donor and gave his right lobe to save him. “The boy arrived with serious complications, including jaundice, fluid accumulation in the abdomen and severe water retention that led to a sudden 15–20 kg weight gain,” says Dr Gaurav Gupta, co-director, Department of Liver Transplant and HPB Surgery at the hospital. “The swelling began to reduce after surgery.”

What triggered the crisis was a genetic mutation that promotes fat accumulation and retention in the liver. But genetics alone was not responsible. “These predispositions often interact with environmental factors such as diet, obesity and insulin resistance,” Dr Gupta explains. “A person with high genetic risk may never develop severe disease if they maintain a healthy lifestyle. But like many teens, this boy regularly consumed ultra-processed and junk foods, which accelerated the damage.”

Why teen obesity and imbalanced diet pushed the boy over the edge

After evaluating the boy, Dr Gupta thought about all means to manage symptoms of liver failure. But transplant seemed the only option. “In such cases, the liver can no longer perform essential functions such as filtering toxins, producing proteins and storing glucose,” Dr Gupta says. “He had jaundice and massive fluid retention, particularly in his legs. Increased pressure in liver veins forces fluid into the abdomen, causing severe swelling that affects breathing and eating.”

A series of investigations revealed multiple genetic mutations that explained the rapid deterioration. “A transplant was necessary because a healthy donor liver does not carry the same mutations,” he explains.

At the time of surgery, the boy weighed nearly 84 kg due to fluid overload. Today, his weight is in the low 60s. “His bilirubin level was above 10 mg/dL and has now returned to normal. All symptoms of liver failure have resolved,” says Dr Gupta. Because the condition had a genetic basis, first-degree relatives were also advised to undergo genetic testing. “The goal is early lifestyle correction to prevent similar damage,” he adds.

How diet hastened liver damage

Genetic testing revealed high-risk variants in the PNPLA3 and GCKR genes, which significantly increase susceptibility to fatty liver disease and are particularly prevalent in the Indian population. “However, genetics alone was not responsible. The diet was the accelerator,” says Dr Arti Pawaria, chief paediatric hepatologist and paediatric transplant physician. Unhealthy dietary patterns, excess calorie intake and reduced physical activity aggravated his genetic risk. “He consumed highly processed foods in his diet like packaged snacks, chips, burgers, cookies, noodles and sodas, usually teen favourites. He had a lot of refined sugar junk foods, which in his case turned out to be hazardous. Schools, parents, and policy makers must work together to reduce children’s exposure to ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks, while promoting affordable, nutritious meals and daily physical activity. Early, population-level dietary interventions can avert a looming burden of advanced liver disease in young Indians,” she says.

Excess fat from obesity releases fatty acids into the bloodstream, overwhelming the liver. “What children eat every day silently shapes their liver health — early dietary discipline can prevent a lifetime of liver disease. Children should be encouraged to eat fresh, home-cooked meals with plenty of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, pulses, eggs, and milk-based proteins. High sugar and refined foods cause fat to accumulate in the liver, even in children who may not look overweight. Healthy eating habits, started early and sustained with physical activity, can prevent fatty liver disease,” says Dr Pawaria.

A transplant that works long-term

People who receive a liver transplant in their teens can live long, healthy lives, with many experiencing a near-normal lifespan due to significant advances in medicine, leading to high survival rates. “The boy can resume school three months after transplant surgery. Slowly he can take up sports too. Post-transplant, obviously the first three to four months are very critical, where we need to keep a track of him. He should avoid infections and his diet has to be managed carefully. But thereafter, he can have an absolutely normal life, even marry and have children as an adult,” says Dr Gupta.

But diet and physical activity will have to be in tandem. “The healthy, transplanted liver portion can correct the genetic defect, provided the recipient adheres to a healthy lifestyle and manages associated metabolic risk factors,” he cautions. The 14-year-old will be on immunosuppressants, too, for the rest of his life.

How to control teen obesity

Preventing teen obesity, experts stress, must be family-driven. Dr Pawaria advises aiming for at least five daily servings of vegetables and fruits, choosing whole grains, lean proteins, low-fat milk, and healthy fats, and prioritising water over sugary beverages. Lime or cucumber-infused water can help curb soda cravings. Always read food labels to avoid hidden sugars, advise nutritionists. Changes should involve the entire family to avoid singling out the child, while allowing occasional treats in controlled portions.

Mindful eating habits also matter. Families should eat together at the table without screens, involve teens in cooking to teach portion control, exercise together, limit screen time, and ensure nine to ten hours of sleep each night. These habits, experts say, may be the most powerful medicine of all.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05