What happens when buildings are razed and spaces in the city redeveloped

A Delhi exhibition questions the role of public memory as it deconstructs remnants of buildings that once stood as symbols of innovation and independence

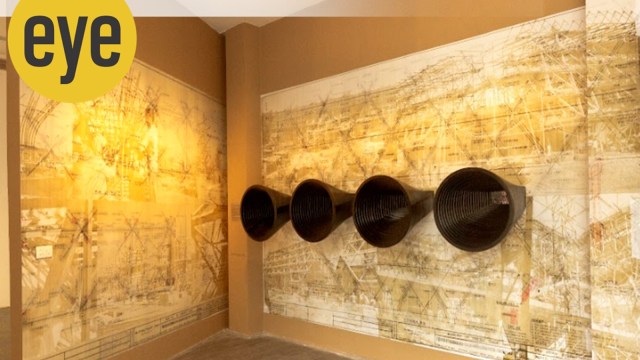

Hall of Nations Credit: SVR (Studio VanRO) Foundation

Hall of Nations Credit: SVR (Studio VanRO) FoundationIt could very well be TS Eliot’s Unreal City where death had undone so many and each man fixed his eyes before his feet. Over the last seven years, Delhi has seen numerous demolitions. JCBs, bulldozers and weak heritage laws have made it possible to raze down structures overnight, creating a vacuum in the country’s modern heritage landscape. So, when a show comes to town that tells us what we’ve lost, we must sit up and listen.

At the STIR Gallery in Delhi is architect-urban designer Rohit Raj Mehndiratta’s exhibition “Memorial to Socialist Modernity”. It looks at three public spaces that have been demolished – Sarojini Nagar’s government colony, the Hall of Nations and the Hindon River Mills in Ghaziabad. Rohit uses photographs, structural drawings and rubble to present what historian Narayani Gupta calls “industrial archaeology”. While the exhibition memorialises the Hall of Nations and the Hindon River Mills building, designed by Rohit’s father Mahendra Raj, the much-acclaimed engineer who collaborated with leading architects to build these landmark structures, Sarojini Nagar colony is a memory map of how people used their most intimate place – their home. Rohit and his partner Vandini Mehta head Studio VanRO, a design and research-based endeavour based in New Delhi and their SVR Foundation engages with the domains of architecture, urbanism and art.

This show, which closes on February 27, can be seen as a counterpoise to the destruction and redevelopment in the city. With the crosscutting of going back and forth in time, it has an urgency to see the present through the demolition of the past. In April 2017, the 108-ft high Hall of Nations was demolished to make way for the multi-crore Pragati Maidan Tunnel, which today poses a potential threat to lives because of water seepage and cracks in the concrete. “What happens when these memories are taken away from us? How does one remember them and get closure?” Rohit says in his note.

It becomes his way of dealing with the anger of demolition. “That’s when this idea of the megaphone abstraction emerged, where one is shouting and nobody is listening.” He has framed four photographs, within bullhorn-like objects, taken on the morning of the demolition of the Hall of Nations, and a visitor is encouraged to use a torch to spotlight the dark cavernous space within which we see the pink rubble of the truncated pyramid structure. In the background are Raj’s structural drawings of the 108-ft high building, superimposed with images of construction techniques and the bamboo work. “The aim was to memorialise everyone including the labourers, the architect, the contractor, and talk about it as something that can never be repeated. It was a sophisticated building, where frugality and economics of the situation which governed India allowed for innovations to happen. The Hall of Nations cannot be built today because we have the luxury of so many materials and we will never do a cast in-situ. Here you can see concrete taken up the staircase,” says Rohit, “Likewise a Hindon River Mills will never happen again because you can now put steel girders and get the span instead of creating arches as Mr Raj did,” he says.

When the Hindon River Mills building was being demolished in 2020, Rohit managed to collect remnants from the building. The 1973 structure was an exercise in imagination and optimal use of resources. New York photographer Stella Snead captured the raw beauty of concrete arches as they leaped across the building providing uninterrupted factory space within the building. Rohit’s photos of the demolition expose the secret behind its strength. “The folded plate edge gutters were designed to run along the length of the building to give lateral stability. They interconnected the twin columns that supported the twin arches. These weren’t visible before, like the reinforcements, they were hidden. It’s almost like photographing an invisible building,” says Rohit.

Hindon River Mills Credit: SVR (Studio VanRO) Foundation

Hindon River Mills Credit: SVR (Studio VanRO) Foundation

He quotes Italian engineer and architect Pier Luigi Nervi, one of Raj’s major influences in his professional life: “The pattern of steel should always have an aesthetic quality and give the impression of being a nervous system capable of bringing life to a dead mass of concrete.” And so, to reinforce how Raj lived by that principle, black metal trays display steel anchors from the site while salvaged high tensile cables, cast in resin, are stories waiting to be told about his technical prowess and precision.

With the Sarojini Nagar exhibit, Rohit presents its dreams and its fears in a series of photographs – of house numbers, of how government allotments are done, of bold wall colours and naked brick walls – taken across three years as the colony was being demolished. Suddenly through the holes in the walls that once held doors and windows, we see trees staking claim to the interiors, cob-web corners lit up with sunlight streaming into a half-eaten plaster. “This is also a reflection of our own aspirations. We can’t blame the government. We run the cycle of capital. We aspire and we force erasure. So we too, are implicated in this process,” says Rohit. In this exhibit, he presents “platters of lived memories”, where he has created a bento box of plastered rubble, cast in resin, as a take on the fast-food recycling of human habitat, where people no longer take ownership of the city.

It is in this “disarticulation of memory”, as architect-historian Amit Srivastava calls it, that lies a call for dialogue and a hope of the “what could be”. Especially at a time when post-independence buildings are under the threat of demolition including Ahmedabad’s Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium and Sanskar Kendra, this show has the potential to become a starting place for conversation around sights, sounds, taste and reuse of public spaces.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05