My Desi Life

We live in complex, interconnected and chaotic times. A true appreciation of desi-ness is probably the only way we can navigate our way through it.

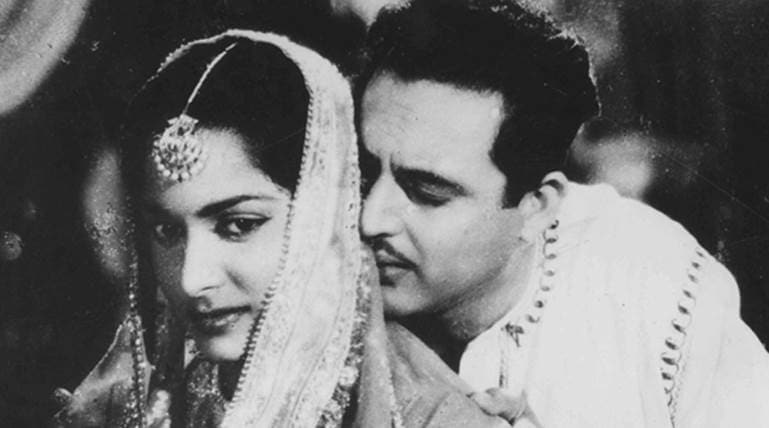

Sense of belonging: Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman in Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960).

Sense of belonging: Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman in Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960).

I am outing myself as a desi. After living and projecting myself as a modern person most of my life, I feel it is time to remove the mask. I should have done this years ago. But I did not have the nerve. It took me a number of years to build up the necessary courage to come out.

I was nudged towards desi-ness by watching the old films of Dilip Kumar and Guru Dutt. The lyrical beauty and cultural resonance of classical Indian cinema slowly became integral to who I came to be. The poetic aesthetics was further enhanced by mushairas that I attended. At one particular mushaira in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, I witnessed a duel between two great poets, Hafeez Jalandhari and Mir Qadri, which ended in the death of Qadri. It was the first time I realised that Urdu poetry had an unfathomable emotional power.

My love for desi-ness increased every time I visited my rather large extended family in Pakistan. In particular, I adored the company of my grandfather, a hakim who devoted his entire life to community service. But it was my late uncle Waheed, the black sheep of the family, who finally rehabilitated me to all things desi. With his unruly beard and traditional dress, he was an archetypal desi man. We used to think that he was slightly unhinged and looked down on him.

There was one thing about uncle Waheed that perplexed the family: his propensity to disappear. One minute he was here with you, the next he was gone. His response to all questions about his disappearing act was simple: “There is more than one way to travel.” Uncle Waheed taught me that plurality and multiplicity, even if it appears to contradict reality, is not to be feared. He transformed desi-ness into a barfi, something I just can’t have enough of.

So now I am a total, unapologetic desi. I love its sense of aesthetics. There is poetry everywhere — not just the invocations of great poets — Mirza Ghalib and Mir Taki Mir, Muhammad Iqbal and Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah, but also in the everyday conversations in local dialects that is reflective, melodious and hard to resist.

There are two characteristics of desi-ness that particularly appeal to me. The first is best expressed by the late Intizar Hussain, novelist and short story writer. Hussain once said that desi-ness is not something that is only defined by geographical territory. Watan, the state, provides one with citizenship and, as such, one has to be loyal to it. But watan has a much larger canvas: it is a civilisational space. He said it was the main source of of his imagination — evident in his novels such as Basti (1979) and Chaand Gahan (1952) and his short stories on “Partition, exile and lost memories”, A Chronicle of The Peacocks (2002). I would add that the civilisation that was — and, hopefully still is — is India. It is the main spring of imagination for all those who inhabit the subcontinent. It is our real and collective watan. It is here that we find the rich ontology of spiritual topographies, symbols, and narratives that define desi-ness and defy the reductive rationalism of modernity.

The second characteristics is essentially a product of the first. Desi-ness does not recognise ambiguity. A civilisational perspective has inherent plurality; it rejoices in multiple narratives, voices, ideas, selves and outlooks. The desi mind has no problem with numerous interpretations of the Qur’an or a plethora of Ramayanas. It sees no ambiguity in what appears to be contradictory to modernity.

Ambiguity is a creation of modernity which champions a single overarching narrative that drowns out all other voices. Desi people live by access and negotiate a surfeit of (seemingly contradictory) sources of knowledge (sacred texts, myths and fables, metaphysics and philosophy, science and objective knowledge) without feeling conflicted. Difference comes naturally to them; it does not have to be “embraced”.

I can hear academics, theorists and all those who like to categorise and pigeon-hole things go, this is so pre-modern. Little could be further from the truth. There is nothing pre-modern about Pyaasa (1957) or Gunga Jumna (1961). Ibn Safi’s novels are as modern as Ghalib, Mir, Faiz and Shakeel Badayuni. Desi-ness can be as modern as we want it to be.

Desi-ness has an equally complex relationship with tradition. It is not something frozen in history, ossified, or oppressive. It is a living, dynamic reality. Tradition is what we remember as best in what has been. That is why tradition is preserved, why it is worthy of respect and mindfulness. But tradition is also what we kill and desecrate by blind repetition.

Desi-ness is a refinement of senses and ethics that can be shared across class, religion and other divides. Notice how Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah is sung by illiterate bards as well as trained musicians, and appreciated alike by the rich and poor, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, and modern and traditional folks.

In essence, desi-ness is transmodern: it takes tradition and modernity and places it over and above both on to a new plane where the emphasis is on beauty, ethics, poetry, common humanity and simple living.

Uncle Waheed turned out to be a mystic: part Sufi, part Bhakti. His secret was that he belonged to an invisible community devoted to serving the poor and the needy. I have travelled far and wide, and met all sorts of people. But I am yet to come across someone like him. “There is nothing worse than breaking a human heart,” he would say.

Of course, it is easy to romanticise desi-ness. But we live in complex, interconnected and chaotic times, surrounded by failed ideologies, -isms and quick fixes. A true appreciation of desi-ness is probably the only way we can navigate ourselves out of all of this. As uncle Waheed used to say, “There is more than one way to be human.”

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05