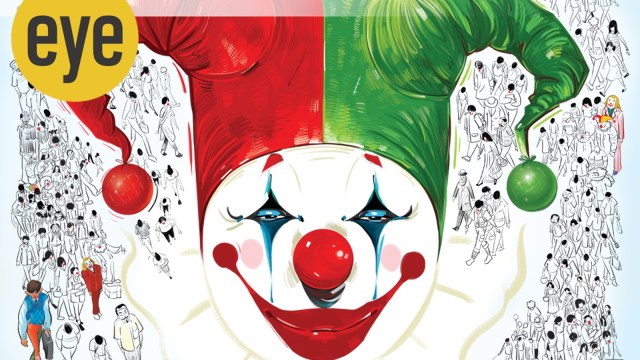

Joker returns: As Joaquin Phoenix revives the cult hero in a new film, why is the clown so dear to us?

With an upcoming film on Batman’s arch-nemesis The Joker, we look at how the figure of the jester has persisted around the world for centuries by mocking the strong and tickling the weak.

The figure of the clown, the jester, the fool who pokes fun at society while prancing on its periphery because he never quite figured out the rules and now doesn’t care, is as old as time, in both history and literature. (Illustration credit: Komal)

The figure of the clown, the jester, the fool who pokes fun at society while prancing on its periphery because he never quite figured out the rules and now doesn’t care, is as old as time, in both history and literature. (Illustration credit: Komal)In the opening scenes of IT, the 1986 horror novel by American writer Stephen King, a clown lures a child into a sewer and eats him. This is not unusual. This clown is a demon, an arrival from an alien planet who has been feasting on the residents of this small town for centuries and the child is nothing special, only the latest in a series of victims that pile as high as Mount Everest. He can shape-shift, become a vampire, a mummy, or even a werewolf — all the classic villains of mid-20th century American television — but it was a clown that King settled on for his default appearance because “some kids are afraid of Frankenstein’s monster, and some kids are afraid of Dracula, but almost all kids are afraid of clowns, with their weird hair, pasty complexions, too-big eyes, and… most of all… their laughing, screaming mouths,” he writes in the book’s foreword.

The figure of the clown, the jester, the fool who pokes fun at society while prancing on its periphery because he never quite figured out the rules and now doesn’t care, is as old as time, in both history and literature. He featured in ancient Egypt, as short people brought in from surrounding lands to amuse the pharaohs; in ancient Rome, where deformed slaves were traded for household amusement; and medieval England, when the occupation finally rose to one of courtly stature, featuring in Shakespeare’s plays. India and China, too, have rich histories of jester-like figures in Birbal, Tenali Rama and Gopal Bhar, who have left their locales behind to capture the national imagination.

His most recent incarnation was in the form of Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker (2019), whose sequel, Joker: Folie à Deux, comes out next month. The films have given the notorious DC Comics character a past, a reason for turning to a life of crime because the system left him behind, echoing numerous mentally ill people around the world whose health insurance fails them, who were abused in childhood, and see violence as the only way out.

Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga in Joker: Folie à Deux.

Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga in Joker: Folie à Deux.

In the 2019 Joker finale, a city rises up to protest extreme inequality and anti-poor policies — all wearing the Joker mask — mirroring the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement in which thousands marched on the streets of New York against the ‘one per cent’ of America’s population that cornered, and still corner, a bulk of the country’s wealth, while wearing Guy Fawkes masks.

This mask was popularised by V for Vendetta, the 1988 British comic which also featured a starkly similar finale, in support of an anarchist vigilante who makes the news by publicly murdering politicians, police officers and bureaucrats in a fascist future. Though not strictly a clown mask, the Guy Fawkes mask smiles, having a “haunting” effect in the comic, according to author Alan Moore in a 2011 interview in The Guardian. “We could show a picture of the character just standing there, silently, with an expression that could have been pleasant, breezy or more sinister… When you’ve got a sea of V masks, I suppose it makes the (Wall Street) protesters appear to be almost a single organism… That in itself is formidable.”

The Indian Express film critic Shubhra Gupta adds that a masked figure such as the clown has been a symbol of “subversion and anarchy” for centuries, adding, “It’s less about the mask and more about what it stands for. Shakespeare’s clowns would often come in between the story’s main figures, give the audience some comic relief, and leave.” She points to yesteryear Hindi film actors, like Shakti Kapoor, Kader Khan and Johnny Walker, who rose to fame playing comic characters, often as sidekicks and served a similar function. The one time the industry tried to buck the trend, it was a “colossal flop”.

“Mera Naam Joker (1970) was disruptive because the clown was central to the story,” says Gupta, recalling the story of a circus clown who, after multiple romantic failures, decides to put on one final performance. “Nobody wanted to see Raj Kapoor in that role. (Through the film), the actor was looking back on his life and career. He was sad and overweight, a character/actor wondering if he’s the main act anymore.” Later, however, the film became a cult classic due to its commentary on the introspection and isolation that goes into artistry, with actor Randhir Kapoor recently lamenting that Indian audiences back then misunderstood the character, only used to seeing clowns as objects of laughter.

This, says Mumbai-based actor Ashwath Bhatt, is a crucial difference between the clown and the fool. “Clowns are laughed at; fools laugh at you,” he says, adding, “In India, anyone with a red nose and make-up is called a joker but it’s derogatory. It’s someone not to be taken seriously. I always tell people, don’t call such a person a joker, call him a clown.”

The distinction is central to clowning, a practice studied by Bhatt for years around the world to bring it to India — both in the form of theatre and therapy. He has led multiple projects to spread this non-native art form in a country like India, which “needs thousands of clowns” due to the stress of modern life. He has done workshops with corporates, dispelling the notion that “to laugh in the office” means you are “unserious”, and taken actors to hospitals and orphanages to make patients and lonely children laugh. “When I do clowning exercises with acting students, across cultures, they say it makes them feel liberated, fearless and joyful. Acting like a clown reconnects you to your inner child,” he says.

Theatre critic Abhilash Pillai agrees, adding that clowning is a completely non-verbal art form that can cut through India’s linguistic diversity to make political statements because “clowns and jokers hit each other and break egos.” He recalls a circus act he saw as a child in which a male and female clown bickered over how to catch a bird at the top of a ladder, a struggle that illuminated the communication and compromises necessary for a healthy domestic life.

But that Indian circus is long gone. Having enjoyed a heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, “when circuses were a part of Nehruvian nation-making”, says Thrissur-based Pillai, most circus companies have died out due to lack of government support and increased regulation on fire hazards, animal cruelty and child trafficking. Moreover, its workers in states such as Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Kerala, Assam and Karnataka remain uncompensated for lifelong injuries. “Governments haven’t given them money (to keep up with changing times), unlike in Europe, where new kinds of circuses have emerged. Indian circus performers only get train concessions,” he says.

“I find the stupidity of modern life really funny — bikes cramming into narrow spaces, everyone always in such a rush,” says Bhatt. He likes it when educated, office-going, high-salary-earning people suddenly crack child-like jokes in living rooms to make their loved ones laugh. “My attitude can irritate people but such chaos is amazing, in a way. Behaving like a clown relaxes you, lets you see the lighter side of life, something we desperately need today. It may not solve the problems of the world, but it certainly helps you deal with them,” says Bhatt.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05