Artist Himmat Shah returns to Delhi — how he moulded mitti and shaped the collector’s dream

Himmat Shah, 91, one of India’s leading modernists, talks about his journey and envisioning a new language in art that offered greater freedom

Himmat Shah at his show in Bikaner House, New Delhi. (Photo credit: Abhinav Saha)

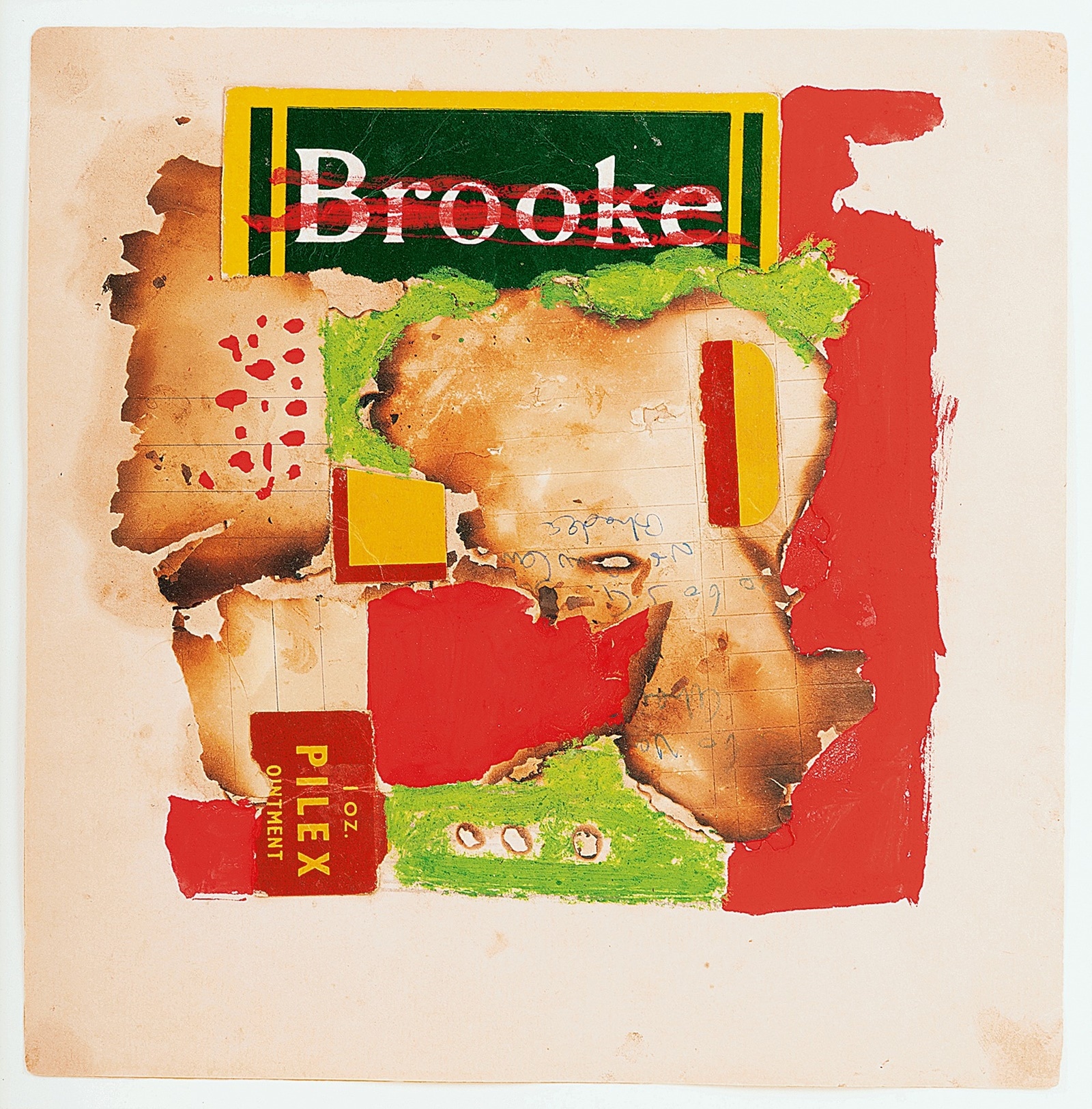

Himmat Shah at his show in Bikaner House, New Delhi. (Photo credit: Abhinav Saha)It was his inherent curiosity and ingenuity that gave birth to Himmat Shah’s distinctive burnt paper technique. Waiting for a friend at his office in the early ’60s, the artist recalls picking sheets of paper impulsively and burning holes on them with his cigarette, resulting in charred edges and intricate overlapping shapes. “I was instantly captivated and ended up producing over 200 works with this technique, despite its fragility and the challenges it posed,” reflects Shah, 91.

Showcased in 1963 as part of the artist collective Group 1890’s lone exhibition at the Lalit Kala Akademi in Delhi, the charred paper collages also intrigued then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Browsing the display during the inauguration, he requested Shah to explain his work. “He said, ‘Arre bhai, main toh anari aadmi hoon, humko kuchh samjhao (I am ignorant, please explain this to me)’. I was embarrassed and told him I didn’t understand much myself. It also must have been difficult for Kalidas to explain his poetry to someone. Both of us started laughing,” recalls the versatile modernist.

The works, acquired by a London-based collector in the mid-’80s, are now with the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA). In the exhibition “Himmat Shah: Ninety and After — Excursions of a Free Imagination”, being presented by Anant Art at Bikaner House in Delhi, these are featured in photographs alongside other archival material, drawings and Shah’s emblematic sculptures in bronze that record some of his constant experiments and solitary pursuits that continued to defy norms but remained undervalued for decades.

“In the case of Himmat, the man and his art are inseparable. Free-spirited and bohemian in his approach, he truly believes in the spirit of artistic adventure. Never fearful about being judged, he was able to break stereotypes, look ahead of his times and innovate with material and form. Driven by the creative process and holistic approach, he does not believe in a compartmentalised approach to art-making and between varied media,” says Roobina Karode, advisor for the exhibition and director-chief curator at KNMA.

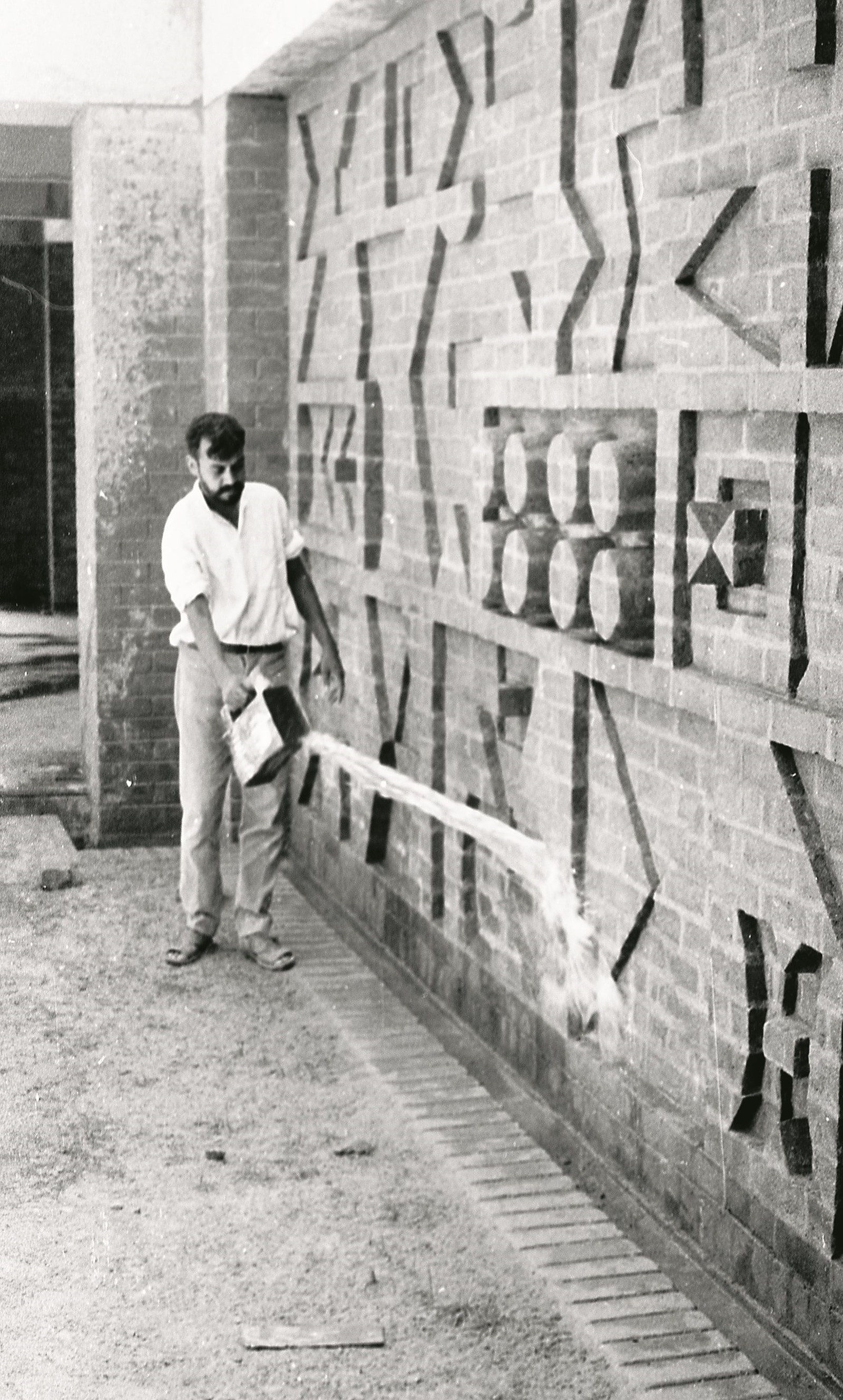

Shah working on the high-relief mural at St Xavier’s Primary School, Ahmedabad (1969) Courtesy: Jyoti Bhatt and Asia Art Archive

Shah working on the high-relief mural at St Xavier’s Primary School, Ahmedabad (1969) Courtesy: Jyoti Bhatt and Asia Art Archive

Born in 1933 into a Jain mercantile family in Lothal (Gujarat) — a flourishing port town during the Indus Civilisation — Shah was captivated by travelling theatrical troupes, bhajan mandals, and potters at their wheels. As an artistically inclined child, he often returned home with clay objects, made by his nimble fingers, for his grandmother. Recognising his passion for art and his reluctance to attend traditional school, he was sent to Bhavnagar for his formative education through alternative teaching methods at Gharshala, where he was mentored by artist-educator Jagubhai Shah. Still in his pre-teens when frequent disagreements began to arise at home, a troubled Shah decided to leave. With his colours and paper in hand, he boarded a train to Junagadh. After spending the night at a temple, a sadhu noticed him and took him to his gaushala, where he spent the following months leading a simple ashram life and venturing into the Girnar forests to sketch the lush landscapes. When a wealthy seth offered him Rs 600 for one of his paintings, Shah had enough to travel to Ahmedabad, where he studied at CN Vidyavihar under the guidance of veteran artist Rasiklal Parikh.

In the early ’50s, he enrolled in a drawing teacher’s course at the Sir JJ School of Art in Mumbai, followed by a stint at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, where his teachers included notable figures such as NS Bendre, Sankho Chaudhuri and KG Subramanyan. Sceptical of formal education and the assessment system, he refused to appear for his exams, opting instead for personal interactions with his teachers, who significantly shaped his modernist approach. “I would only go to college if I was up to it. I used to spend a lot of time outdoors or reading books on art and design in the library. At night, I would go to the railway station to sketch, as it had light for 24 hours. I completed all exercises given in class, but didn’t give any exam. I didn’t think a certificate in art held any real value,” says Shah.

When he boarded the train to Delhi in 1962 with artist Balkrishna Patel, he carried with him the spirit of defiance and the lesson imparted by Bendre: for an artist, life itself is his canvas. “I had no money, and I didn’t know what I would do in Delhi, but I decided to go anyway,” recalls Shah. It took several years for his fortune to change. Living in a barsati in Karol Bagh, he was introduced to artists J Swaminathan and Jeram Patel. He eventually became a core member of the short-lived yet influential Group 1890, named after the house number of Jayant Pandya, where the group’s manifesto was drafted in 1962.

Tempera, pen and ink on burnt paper (1962) Courtesy: Himmat Shah and KNMA

Tempera, pen and ink on burnt paper (1962) Courtesy: Himmat Shah and KNMA

“Our aim was to challenge existing notions of art and envision a new language that offered greater freedom,” says Shah. Swaminathan also introduced him to Mexican poet, diplomat and art enthusiast Octavio Paz. Shah recalls Paz sitting on cushions on the floor of his barsati, sifting through his work before recommending him for a French government scholarship to study under artists SW Hayter and Krishna Reddy at the renowned printmaking studio Atelier 17 in Paris. In the French capital in 1966, captivated by his visits to European museums, Shah immersed himself in the works of masters such as Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Joan Miró and Henri Rousseau. He also spent time in London with sculptor Raghav Kaneria, before returning to Delhi in 1967. “In that one year, I gained immense knowledge and felt re-energised. It also provided me with a fresh perspective on what existed in India,” says Shah.

Though he had already gained recognition before his departure for Europe — including a well-received drawing exhibition in Delhi in 1964 — his return marked a period of significant transformation in his oeuvre. He spent nearly two years creating brick, cement and concrete relief murals at St Xavier’s School in Ahmedabad on the invitation of his architect-friend Hasmukh Patel. The geometric abstractions continued to characterise his work as he explored new forms and materials.

The ’70s saw him sculpt in direct plaster and produce terracotta pieces moulded with objects collected from junk markets and other sources. His ‘silver paintings,’ made with plaster of Paris and sand, were adorned with silver paint and silver leaf (warq). While many of these were lost during the Delhi floods in the late ’70s, Shah reflects that the “experience and joy of creating them” remain with him.

Undeterred by adversities, he continued to draw even when resources were scarce. The ink-and-pencil renderings he created, therefore, not only reflect his artistic journey but also capture his deepest contemplations, yielding intuitive strokes that produced unpredictable forms — ranging from faces marked by anguish to inspirations drawn from archaic symbols and geometric forms. During the two years of Covid, confined to his home in Jaipur and unable to visit his studio, he deliberated upon the complexities of human emotions. “Drawing is essential, regardless of the medium you choose; to truly grasp inner beauty, one must also understand the lyric,” Shah asserts.

Photographer Raghu Rai, who has been a close friend since the early ’70s and also shared an apartment with Shah for several years in Delhi’s Rabindra Nagar, notes how his art is a reflection of his simple and honest life. “He speaks his mind, regardless of the potential consequences. His candidness may have irked many, and not everyone may appreciate his intuitive opinions, but he is a pure soul. Warm and genuine, his responses come from the heart and his works are not influenced by any trends or style,” says Rai.

It was fellow artist PR Daroz, who fired his first clay head at the Garhi Studios, which became his home for over two decades through the ’80s and ’90s. It is where he shaped earth, often sourced from the potter’s colony near the New Delhi railway station. “For almost two years, I photographed every sculpture I created to understand the nuances of its expression. Living alone in that small room at Garhi, I would work all day and sometimes even wake up at night to continue. My teachers instilled in me the belief that our goal should always be to create something new. The material guides me, and I follow,” says Shah, adding, “Most artists in India have adapted from the West; very few have been truly innovative.”

Describing Shah’s studio in an essay on the website ‘Critical Collective’, artist Krishen Khanna wrote: “His studio is a storehouse of objects he has picked up and which outgrew their use and found their way to junkyards and the rubbish heap. Old bottles, bits of metal, knives of all sorts, wires, ropes, pots and pans, all resuscitated and given a new status, coexisting happily with clay, plaster, pigments, chemicals. Heads at various stages in the making. All, including him, covered with a fine white dust. It is more like a magician’s cave than a conventional studio.”

For Shah, every object possesses a soul and it is his purpose to grant it an afterlife. So, on a trip to Jaisalmer, staying in a village with nomads in the Thar desert in the mid-1980s, he designed a sculpture outside their homes with wood, stone and other available material. While he developed his own slip-casting technique for terracotta, in early 2000s, he also began casting in bronze. The forms included his distinguished stylised heads, which he attributes to his memories of playing in the pond with friends as a child. “I did not know how to swim, so I would just sit and watch. As they dived in, their heads emerged from the water at first — that image has stayed with me,” recalls Shah.

His studio is still filled with an array of tools and found objects collected from obscure locations, along with mitti (clay) ground by hand and soaked in water for years to enhance its strength. “For him, art is about creative discovery, a mysterious revelation, not only about perfecting form,” notes Karode. Shah emphasises that his own quest for fulfillment remains incomplete. “My work is my weapon, and I regard creativity as the greatest celebration; there is no greater tool. It is not merely an act of the mind; it is an act of the body. Art can only be understood through the gestures of the body. The possibilities are endless. I am still striving to discover my own sculpture; it has not yet been born.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05