Are Insta moments taking the thrill out of hilltops?

The modern landscape of communications has blanched the mystique associated with travel. With images of every corner of the planet a click away, travel no longer offers the thrill of discovery

For centuries, the high-altitude view has enamoured poets and philosophers alike. There is something surreal about observing the world from a height

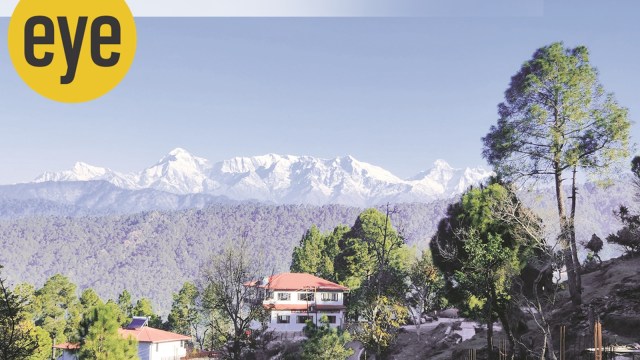

(Credit: Rohan Banerjee)

For centuries, the high-altitude view has enamoured poets and philosophers alike. There is something surreal about observing the world from a height

(Credit: Rohan Banerjee)Travel was once an essential endeavour if you wanted to discover a world beyond your own. The beauty of a faraway region could be appreciated only after long days of voyaging. The minutiae of life in a new city – the local customs, the provincial cuisine – had to be experienced first-hand. Books and travel magazines, if you took the trouble to consult them, may have painted broad brushstrokes of your destination but the canvas remained inchoate until you journeyed to see it with your own eyes.

Now, in the digital age, the world can be viewed in the palm of one’s hand. In How To Travel Without Seeing, writer and poet Andrés Neuman, remarked: “These days we go places without moving. Sedentary nomads, we can learn about a place and travel there in an instant. Nevertheless, or perhaps consequently, we stay at home, rooted in front of the screen…Wherever we go, we remain within the same landscape: the landscape of communications.”

This modern landscape of communications has blanched the mystique associated with travel. There is little room for surprise when day-by-day itineraries and listicles of ‘hidden gems’ clinically dissect every conceivable locale. With images of every corner of the planet just a few clicks away, travel no longer offers the thrill of discovery. Instead, it now lures you with a different promise: an escape from monotony.

When you travel, you get a chance to lay aside your assigned roles and duties, and play out an alternate existence. It affords a brief respite from the humdrum of home. No matter your travel philosophy – whether it’s must-see-top-sights or slow, deliberative exploration – there is a desire to leave behind the quotidian life, to shape your vacation days as counterpoints to your daily routines. For some, an annual visit to a favourite city can be enough to scratch this itch for change; for others, a whirlwind trip of a new country is an adequate taste of the exotic. And then there are those, whose love for unusual travel can manifest in more ominous ways.

If you belong to this last category, you are sure to exhibit the peculiar characteristics of this itinerant species. You can willingly forego the benefits of plumbing and go days without taking a bath. When someone makes you walk for miles in the wilderness – trudging through mud and snow, stumbling over boulders and springs – you are able to successfully quell your desire to bash their head in with a rock. You think nothing of getting drenched in the rain and being crisped by the sun, all in the course of one morning. Bent under the weight of your pack and plodding uphill on weary legs, you can suppress the longing to leap off the cliff just to bring an end to your suffering. And, most crucially, you can dip into your deepest well of fortitude, plumb the depths of your forbearance, to endure a breakfast of oats porridge.

Later, when you return to civilization with tales of your (mis)adventures and people look at you with a mix of concern, pity, and alarm, you likely assuage them by saying that no holiday can feel as enlivening as one spent hiking in the great outdoors. You’re quite right, of course.

In 1923, an editorial in The Guardian touted the benefits of ‘rambling’ in the mountains and moorlands, thus: “… every time one spends a long day among the heather or the peat; a coating of the almost inevitably incipient parasitism that comes of living always in a crowd falls from you; you “breathe deep and are yourself”..”. Over a century later, these words ring truer than ever.

To city-dwellers accustomed to being boxed in by glass-and-steel towers, having the run of an alpine meadow can feel liberating. While the traffic gridlock at busy intersections triggered rage, waiting for mountain goats to cross a trail prompts a smile. On a steep ridgeline, the din of urban spaces can be traded for silence broken only by the whip of the wind. Every year, thousands of hikers make a beeline for the mountains – venturing into wild expanses untamed by humanity – hoping to earn a measure of this solitude; preferably, while enjoying a mountaintop view.

For centuries, the high-altitude view has enamoured poets and philosophers alike. There is something surreal about observing the world from a height – to see the hills rolling into the horizon, streams thinning into ribbons, and lakes sparkling like freshly-minted coins. As Robert Macfarlane so eloquently wrote in Mountains of the Mind, when you’re on top of a mountain: “… the only limits to how far you can see are the mechanical limits of your vision. Otherwise, you are panoptic, satellitic, an all-seeing I…. And that is an unforgettable sensation.”

This sensation can also acquire a dark edge. The history of mountaineering is littered with stories of climbers – George Mallory, Günther Messner, and countless others – whose obsession with summits claimed their lives. But for the amateur hiker, this ‘inverted gravity of mountain-going’, as Macfarlane calls it, need not be only about conquering peaks. After all, there is much else that mountain travel has to offer and every foray into the highlands can feel different.

At Beas Kund, you are greeted by a phalanx of snow-capped sentinels standing vigil over the emerald pool as the headwaters of the river thread through the sparse valley. During a night march to Pangarchulla, the clear skies and starlight turn the mountainside into a moonscape. In the Rupin Valley, you can camp at the foot of a thundering, three-tiered waterfall, a bank of yellow blossoms neighbouring your tent. On the rope lines leading up to Friendship Peak, a bout of vertigo can assail you when you peer into the depths of a crevasse. In the forests above Rimbick, where the hills of North Bengal crest into Sikkim, rhododendrons abound, and further north-west, the trail to Kuari Pass leads you into an icy, inhospitable wasteland.

These sights, though awe-inspiring, are rarely unforeseen. In the course of your research and preparation, you inevitably trawl through trekking websites and galleries highlighting the many photogenic vistas that the hiking route will present. And so, later, when you stand on a ledge after hours of climbing and look at the chevron of jagged peaks on the horizon, you are robbed of the feeling of newness, of having discovered this view.

But, as it turns out, this is of little consequence. You will keep returning to the mountains – hauling your rucksack and clutching your trekking poles – because it is not discovery that you’re after. It is the opportunity to flee the ordered life you’ve built in the plains, to collect memories that will sustain you through months of monotony until you can travel again.

The writer is a Mumbai-based lawyer

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05