What happens during remand hearings? This is what a study suggests

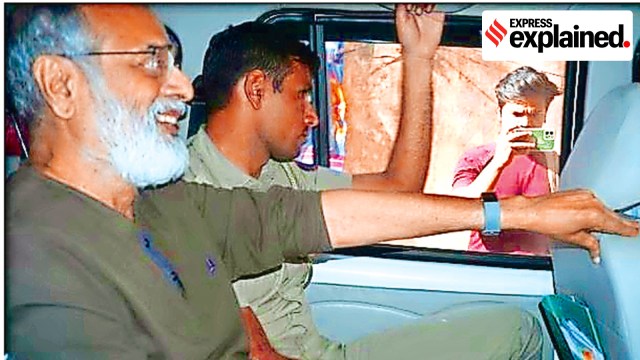

The Supreme Court this week directed the release of jailed journalist Prabir Purkayastha on the ground that due-process safeguards were not followed in his arrest and detention, and that his constitutional rights had been violated.

After arrest, Purkayastha was produced before a designated judge early in the morning, and sent to seven days’ police custody. He was not given an opportunity to defend himself through legal counsel of his choice, and not informed of the grounds of arrest, as required by Article 22 (1) of the Constitution.

After arrest, Purkayastha was produced before a designated judge early in the morning, and sent to seven days’ police custody. He was not given an opportunity to defend himself through legal counsel of his choice, and not informed of the grounds of arrest, as required by Article 22 (1) of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court this week directed the release of jailed journalist Prabir Purkayastha on the ground that due-process safeguards were not followed in his arrest and detention, and that his constitutional rights had been violated.

After arrest, Purkayastha was produced before a designated judge early in the morning, and sent to seven days’ police custody. He was not given an opportunity to defend himself through legal counsel of his choice, and not informed of the grounds of arrest, as required by Article 22 (1) of the Constitution.

Role of the magistrate

The judgment is a reminder of the constitutional rights at stake during first production and remand, a critical stage in the criminal legal process. But while the judgment spotlights the right of the accused to know the grounds for arrest to protect their right to life and liberty under Article 21, it does not focus on the role of the judiciary to ensure these safeguards, and to oversee police actions.

Article 22(2) says every arrested person shall be produced before a magistrate within 24 hours — this is called “first production”. The magistrate/ judge can authorise further detention in police custody (for interrogation) or judicial custody through remand hearings.

This is not a mechanical procedural step. It requires judicial scrutiny to ensure that statutory and constitutional safeguards are realised in letter and spirit.

What happens in court

An ethnographic study by Project 39A at National Law University Delhi looked at the everyday functioning of magistrate courts during regular hours across the six district court complexes in Delhi over a three-month period, including the role of the magistrate, lawyers, police, and accused.

The researchers observed the manner in which the public interaction of the magistrate, courtroom dynamics, and social hierarchies influenced the experience of the accused at first production and remand.

The findings suggest most magistrates do not fully realise the constitutional and statutory protections at first production and remand. Violations such as those flagged by the SC in Purkayastha’s case are not uncommon.

Key findings of the study

📌 While the extent of intervention and engagement of magistrates varied, the proceedings tended to emphasise compliance on paper. Most magistrates ensured that the Arrest Memo — which contains information on the circumstances of arrest and intimation to family — and Medico-Legal Certificate (MLC) — based on a medical examination of the accused — were present on file.

The observations suggested that the legal system acknowledges that these documents are important to protect the accused from illegal detention and torture in this vulnerable phase in custody.

However, the paperwork may not always be comprehensive or even an accurate record of the experience of the accused.

For instance, Arrest Memo was often filled inside the courtroom, with officers at times asking the accused about details of their family minutes before production. This meant that intimation to family, which is a crucial safeguard in the arrest process, was not meaningfully realised.

📌 Magistrates rarely interacted with the accused to confirm their experience with the information provided in the documents. Meaningful interactions with the accused and their lawyers and family on questions of age, circumstances and grounds of arrest, and experience in custody is crucial to ensure that the constitutional rights of the accused are fully realised during the proceedings.

The study found that violations were often ignored or corrected in the paperwork, without consideration of its consequences or impact on the rights of the accused. At first production, standard explanations for injuries — accident or public beating — were usually accepted without further inquiry.

📌 There is no standard format for Arrest Memo or MLC, which adds to the lack of clarity about the information necessary to ensure the rights of the accused are protected. There are also gaps in the forms — for example, in the Arrest Memo in use in Delhi, there is no column for age, and any inquiry in this regard is left to the discretion of the magistrate.

The Supreme Court’s emphasis on the distinction between the formal reasons for arrest — often included in the Arrest Memo — and meaningful communication of the grounds of arrest in writing, highlight another aspect where the presence of the Arrest Memo alone is not adequate confirmation of due-process rights of the accused.

Legal representation

It was observed that most production hearings took place without legal representation for the accused, with magistrates not intervening to secure the accused’s right.

Remand lawyers, a category of legal aid counsel who are appointed to ensure defence representation at the pretrial stage, were generally absent from the court. Where remand lawyers were present, they were rarely given the opportunity to consult with the client and seek instructions. Very few intervened and pressed any arguments on behalf of the accused.

While lawyers asked for a copy of the FIR, they rarely sought a copy of the Arrest Memo or MLC, to which the accused is entitled.

Purkayastha’s case illustrates that occasionally remand counsel may be invited to represent the accused as a way to bypass the right of the accused to their own private counsel in violation of Article 22(1).

Structural barriers

📌 First production and remand proceedings do not even appear to be accorded proper time in the daily workload of the magistrate. These matters are heard at random, together with or in between other proceedings.

📌 The heavy workload of magistrates, and a perception that pretrial proceedings are unimportant, might lead to magistrates not treating every production matter as warranting careful inquiry. Production matters are not even mentioned in the cause list, the most publicly visible document of the court’s schedule. This is not the only category of matters that is excluded — but the exclusion does undermine the substantive importance of this procedural requirement.

📌 The lack of publicly available record or schedule of pretrial remand matters, and the overreliance on communication with the police for information on productions from police custody, causes confusion for lawyers and family of the accused and compromises the rights of the accused.

Sikora is Senior Associate, Project 39A, NLU Delhi. Lokaneeta is Professor of Political Science and International Relations, Drew University, USA. They led the first-of-its-kind study, ‘Magistrates & Constitutional Protections: An Ethnographic Study of First Production and Remand in Delhi Courts’

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05