Why the first-ever satellite tagging of a Ganges dolphin is significant

Here is all you need to know about the Gangetic river dolphin, the threats that it is faced with, and efforts made towards its conservation.

The Ganges river dolphin observed in the Hoogly river at Katwa in West Bengal earlier this year. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Ganges river dolphin observed in the Hoogly river at Katwa in West Bengal earlier this year. (Wikimedia Commons)The first ever Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) was tagged in Assam on Thursday (December 18), in what is being deemed as a historic milestone for Project Dolphin, the movement aimed towards conserving India’s National Aquatic Animal.

Happy to share the news of the first-ever tagging of Ganges River Dolphin in Assam—a historic milestone for the species and India!

This MoEFCC and National CAMPA-funded project, led by the Wildlife Institute of India (@wii_india) in collaboration with Assam Forest Dept and… pic.twitter.com/2lSUHVltBN

— Bhupender Yadav (@byadavbjp) December 18, 2024

The tagging exercise will help in understanding the species’ seasonal and migratory patterns, range, distribution, and habitat utilisation, particularly in fragmented or disturbed river systems, according to the press release by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

Ganges river dolphin

There are some 40 extant species across multiple families that are referred to as dolphins. The family Platanistidae comprises two extant species of Indian river dolphins — the Indus river dolphin and the Ganges river dolphin, both of which were considered to be the same species till the 1970s.

The Conservation Action Plan for the Ganges River Dolphin, 2010-2020, describes male Gangetic dolphins as being about 2-2.2 metres long, and females as a little longer at 2.4-2.6 m. An adult dolphin could weigh between 70 kg and 90 kg. They feed on several species of fishes, invertebrates, etc.

Ganges river dolphins are frequently found alone or in small groups, and are known to be extremely shy around boats, making it hard for scientists to observe them.

They go by a number of local names across their range including susu, soons, soans, or soos in Hindi, shushuk in Bengali, hiho or hihu in Assamese, and bhagirath, shus or suongsu in Nepali. Culturally, the species is often associated with Ganga and is occasionally depicted as the vahana (vehicle) of Goddess Ganga.

Behind declining population

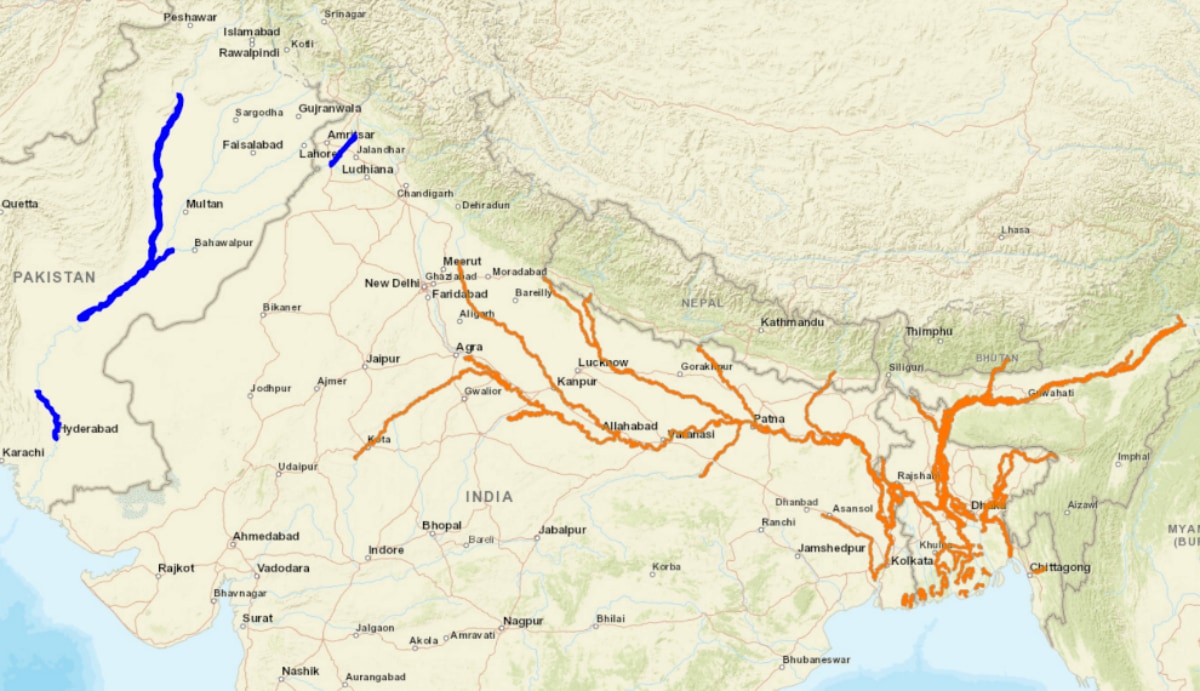

The Ganges river dolphin was once found across the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna and Karnaphuli-Sangu river systems of Bangladesh and India, and the Sapta Koshi and Karnali Rivers in Nepal. (See Map). There was a time when Gangetic dolphins could be spotted as high upstream in the Ganges and its tributaries as the Himalayan foothills.

Distribution of Indus (blue) and Ganges (orange) river dolphins. (Wikimedia Commons)

Distribution of Indus (blue) and Ganges (orange) river dolphins. (Wikimedia Commons)

However, according to the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) the species is now extinct in most of its original distribution ranges, with only 3,500 to 5,000 individuals alive today. Both the Indus and Ganges dolphins have been listed as ‘Endangered’ in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List since the 1990s. This classification indicates that the species has “a very high risk of becoming extinct in the wild”.

Behind the species’ declining population and endangered status are a number of factors. These include:

- Construction of dams and barrages in rivers, which restrict these dolphins’ movement and migration patterns, food supply, and breeding behaviours;

- Riverine pollution, which makes these dolphins’ habitats unlivable for the species and others it depends on for food;

- Poaching for these dolphins’ oily blubber, or accidental entanglement in fishing nets; and

- Habitat shrinking, as rivers dry up, and become less navigable.

Attempts at conservation

This is why, since the 1980s, various efforts have been made to conserve the elusive species, and restore its population to pre-20th century levels. But so far, these efforts have not borne much fruit.

- 01

WILDLIFE ACT PROTECTION

After the launch of Ganga Action Plan in 1985, the government in 1986 included Gangetic dolphins in the First Schedule of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. This was aimed at checking hunting and providing conservation facilities such as wildlife sanctuaries for the species. For instance, the Vikramshila Ganges Dolphin Sanctuary was established in Bihar under this Act.

- 02

CONSERVATION PLAN

The government prepared The Conservation Action Plan for the Ganges River Dolphin 2010-2020, which “identified threats to Gangetic Dolphins and impact of river traffic, irrigation canals and depletion of prey-base on Dolphins populations”. The idea was to holistically identify factors that were leading to the species population declining, and address these issues.

NATIONAL AQUATIC ANIMAL: In 2009, then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, declared the Gangetic river dolphin as the National Aquatic Animal of India, in what was an attempt to boost awareness of the species and community participation in its conservation.

- 03

PROJECT DOLPHIN

This is the latest effort to aid the species’ conservation, launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2020. While announcing the project, Modi said that this project will be on the lines of Project Tiger, which has been successful in reviving the tiger population in the country.

The latest dolphin tagging exercise is among the many initiatives made under the project, which according to its website “involves a systematic status monitoring of the target species and their potential threats, in order to develop and implement a conservation action plan.” The lightweight tags are designed to emit signals that will be picked up by satellites when these species surface, which “will contribute to evidence-based conservation strategies that are urgently needed for this species,” Virendra R Tiwari, director of the Wildlife Institute of India said.

Notably, Project Dolphin views the Gangetic river dolphin as an “umbrella species” whose conservation “will contribute to the wellbeing of associated habitat and biodiversity, including humans”.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05