As thousands of earthquakes rock Iceland, a volcanic eruption to follow?

The Iceland Met Office has said that there is a “considerable” likelihood of a volcanic eruption occurring over the next few days. What has this got to do with earthquakes?

Lava spurts and flows after the eruption of a volcano in the Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland, July 12, 2023. (Civil Protection of Iceland via REUTERS/File/Representational)

Lava spurts and flows after the eruption of a volcano in the Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland, July 12, 2023. (Civil Protection of Iceland via REUTERS/File/Representational) A state of emergency has been declared in Iceland, after a swarm of 800 earthquakes rocked the island country’s southwestern Reykjanes peninsula in under 14 hours on Friday (November 10).

Around 1,400 earthquakes were measured in the previous 24 hours, and over 24,000 have been recorded in the peninsula since late October. The most powerful of these quakes had a magnitude of 5.2, and hit about 40 km from Reykjavík, Iceland’s capital, on Friday.

Since Friday, seismic activity has somewhat diminished but not stopped. Scientists say it is unlikely to, anytime soon.

Just what is happening in Iceland?

Iceland is located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, technically the longest mountain range in the world, but on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. The ridge separates the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates — making it a hotbed of seismic activity.

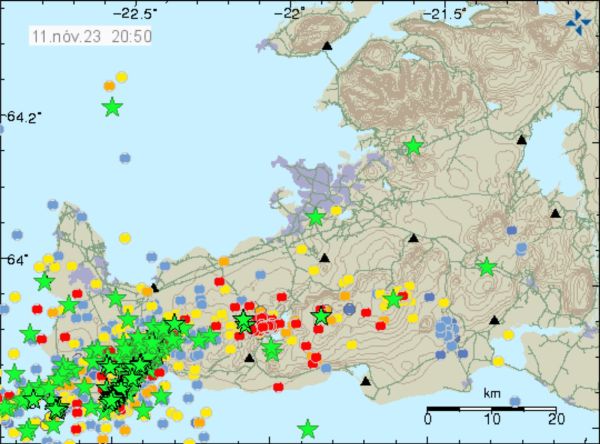

Reykjanes Peninsula: earthquakes in the last 48 hours (updated 8.50 pm Saturday, Iceland time). Stars are quakes of magnitude>3. Colours indicate hours since quake — red for 0-4 hours, orange 4-12 hours, yellow 12-24 hours, light blue 24-36 hours, dark blue 36- 48 hours. (Iceland Met Office)

Reykjanes Peninsula: earthquakes in the last 48 hours (updated 8.50 pm Saturday, Iceland time). Stars are quakes of magnitude>3. Colours indicate hours since quake — red for 0-4 hours, orange 4-12 hours, yellow 12-24 hours, light blue 24-36 hours, dark blue 36- 48 hours. (Iceland Met Office)

On average, Iceland experiences around 26000 earthquakes a year according to Perlan, a Reykjavik-based natural history museum. Most of them are imperceptible and unconcerning. But sometimes, a swarm of earthquakes — a sequence of mostly small earthquakes with no identifiable mainshock — is a troubling precursor to a volcanic eruption.

According to scientists belonging to the Iceland Met Office (IMO), that is exactly what is happening now.

How can earthquake swarms be portents for volcanic activity?

Deep under the Earth’s surface, intense heat melts rocks to form magma, a thick flowing substance lighter than solid rock. This drives it upwards and most of it gets trapped in magma chambers deep underground. Over time, this viscous liquid cools and solidifies once again. However, a tiny fraction erupts through vents and fissures on the surface, causing volcanic eruptions.

Movement of magma underground shows up as deformation on surface. This is often accompanied by earthquake swarms. This figure shows the extent of the deformation and subsidence on the surface surrounding the Uturuncu volcano in Bolivia. It also provides a possible explanation for how the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body (APMB) may be causing this deformation. (Wikimedia Commons)

Movement of magma underground shows up as deformation on surface. This is often accompanied by earthquake swarms. This figure shows the extent of the deformation and subsidence on the surface surrounding the Uturuncu volcano in Bolivia. It also provides a possible explanation for how the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body (APMB) may be causing this deformation. (Wikimedia Commons)

Now, the movement of magma close to Earth’s surface exerts force on the surrounding rock, which often causes earthquake swarms. Now, the underground movement of magma does not necessarily lead to an eruption. But closer it gets to the surface, more likely an eruption is, and more frequent symptomatic earthquake swarms get.

After the ongoing spell of seismic activity began, IMO scientists on October 27 said that it was “the response of the crust to the stress changes induced by continued magmatic inflow at depth beneath the Fagradalsfjall volcanic system.”

When and where is an eruption likely to take place?

Fagradalsfjall lies about 40 km to the southwest of Reykjavík and is the “world’s newest baby volcano.” It had been dormant for eight centuries before erupting in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Since the 2021 eruption, tourists from across the world have swarmed (sic) to Fagradalsfjall to catch a glimpse of molten lava flowing gushing onto Earth’s surface.

The IMO, on Friday, noted that “a considerable amount of magma is moving in an area extending from Sundhnjúkagígum in the north towards Grindavík.” In its most recent statement on Saturday, IMO said that this “poses a serious volcanic hazard”, with the magma, at its shallowest depth just north of Grindavík, being just “800 m under Earth’s surface”.

Magmatic dikes form when magma flows into a crack then solidifies, either cutting across layers of rock or through a contiguous mass of rock. The red line shows the dike intrusion observed by scientists. The site of the eruption will lies somewhere on it. (Iceland Met Office)

Magmatic dikes form when magma flows into a crack then solidifies, either cutting across layers of rock or through a contiguous mass of rock. The red line shows the dike intrusion observed by scientists. The site of the eruption will lies somewhere on it. (Iceland Met Office)

While it is impossible to pinpoint the exact location of an eruption, it is likely to be around this area. With regards to when the eruption will take place, the IMO said that it could be “possible on a timescale of just days.”

Grindavík, a town of 4,000 on Iceland’s southern coast lies about 10 km from the site of the previous Fagradalsfjall eruptions. It has been evacuated as a precaution.

How many active volcanos does Iceland currently have?

Iceland is home to some of the most active volcanoes in the world, with volcanos being an integral part of the island’s landscape and culture.

Currently, it boasts of 33 active volcanoes which have erupted over 180 times in the past 1,000 years. According to United States Geological Service, active volcanos are those which have “erupted within the Holocene (the current geologic epoch, which began at the end of the most recent ice age about 11,650 years ago),” or which have “the potential to erupt again in the future.”

One of Iceland’s most famous volcanoes is Eyjafjallajökull. In 2010, this volcano erupted and caused a massive ash cloud to spread across Europe. The ash cloud disrupted air travel for weeks and caused billions of dollars in damage. Other famous volcanoes include Hekla, Grímsvötn, Hóluhraun, and Litli-Hrútur (part of the Fagradalsfjall system).

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05