‘15 minutes of terror’: What should happen in the final minutes of Chandrayaan-3 lander’s descent on the Moon

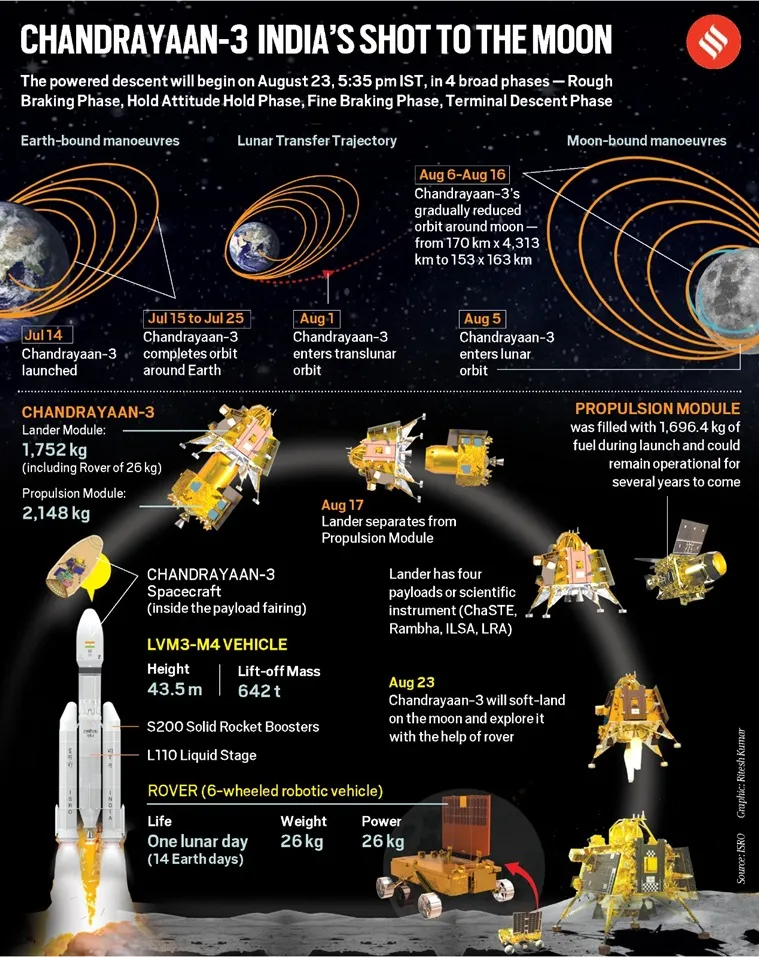

The Chandrayaan-3’s Lander Module’s final deboosting operation has reduced its orbit to 25x134 km around the Moon, Isro said on Sunday. The powered descent will begin on August 23, 5:45 pm, in four broad phases: Rough braking phase; Attitude Hold Phase; Fine Braking Phase; Terminal Descent Phase.

The key focus now is on the final landing phase scheduled for Wednesday (August 23) evening — with the final 15 minutes (where the landing failed in the Chandrayaan 2 mission) holding the key to a successful mission. (Artist's impression photo, via X.com/ISRO)

The key focus now is on the final landing phase scheduled for Wednesday (August 23) evening — with the final 15 minutes (where the landing failed in the Chandrayaan 2 mission) holding the key to a successful mission. (Artist's impression photo, via X.com/ISRO) The critical technical manoeuvre that the Chandrayaan-3 lander will have to perform on August 23 when it enters the final 15 minutes of its attempt to make a soft landing on the Moon will be to transfer its high-speed horizontal position to a vertical one — in order to facilitate a gentle descent on to the surface.

These final 15 minutes on Wednesday evening will determine the success of the mission. In July 2019, after the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) aborted the first attempt to launch the Chandrayaan-2 mission, K Sivan, then chairman of India’s space research body, had described this phase as “15 minutes of terror”.

Dr Sivan’s description captured the essence of the complexity of the mission’s final phase — the one in which Chandrayaan-2 failed after the Vikram lander did not switch appropriately from the horizontal to the vertical position, and hurtled on to the surface of the Moon when it was entering the “fine braking phase” 7.42 km from the lunar surface.

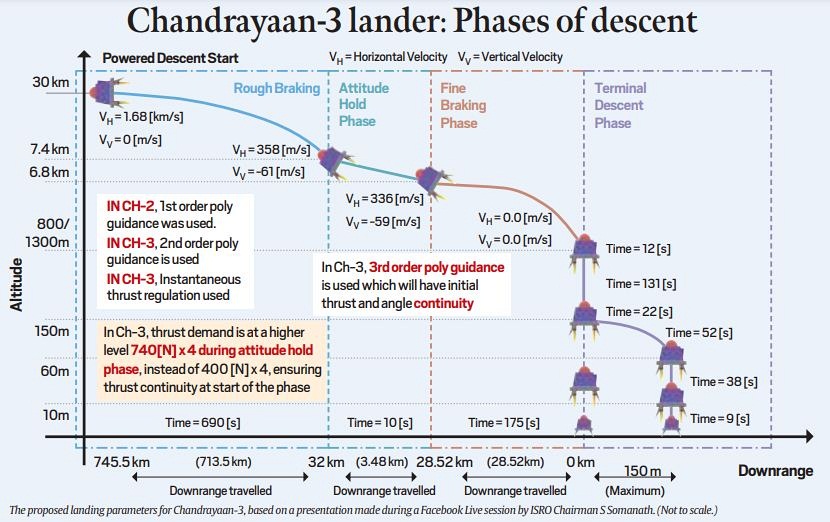

The proposed landing parameters for Chandrayaan-3, based on a presentation made during a Facebook Live session by ISRO Chairman S Somanath.

The proposed landing parameters for Chandrayaan-3, based on a presentation made during a Facebook Live session by ISRO Chairman S Somanath.

The final deboosting of the Chandrayaan-3 lander was completed on Sunday to reduce its orbit to 25X134 km around the Moon.

Rough Braking Phase

The other critical part of the landing is the process, which will take place simultaneously, of reducing the lander’s horizontal velocity from a range of 1.68 km/sec (more than 6,000 km/h) at a height of 30 km from the lunar surface to almost zero for a soft landing at the designated site about 70 degrees South latitude. The landing is scheduled around 6.04 pm India time on August 23, ISRO has said.

“Chandrayaan-3 is tilted almost 90 degrees at this time (when the landing process begins at 5.47 pm on August 23) but it needs to be vertical (for a landing). This process of turning the lander…is a very interesting calculation mathematically. We have done a lot of simulations. This is where we had a problem the last time (which led to the crash of Chandrayaan-2 on September 7, 2019),” ISRO Chairman S Somanath said on August 9.

Follow Chandrayaan-3 Moon Landing Live Updates

“The transfer from the horizontal position to the vertical position…is the trick that we have to play over here. We have to ensure that the fuel consumed is less, the distance calculation is correct and all the algorithms are working properly,” Dr Somanath said.

The 2019 disappointment

The landing in 2019 was seemingly on track until around 3 minutes before the final “terminal descent phase”, when the lander ended up spinning more than 410 degrees, and deviated from its calibrated spin of 55 degrees to crash on the Moon.

The speed and direction of the lander is controlled by 12 onboard engines. “The lander’s four engines are used to reduce the velocity and there are also eight small engines to control the direction of the descent. The engines are throttleable and the thrust can be varied from 800 Newton to a lower value. It can keep the lander hovering on the Moon’s gravity,” Dr Somanath said.

The horizontal velocity of 1.68 km/sec at the beginning of the landing process (vertical velocity is zero at this stage) has to be first reduced to 358 m/sec (about 1,290 km/h) horizontal velocity and 61 m/sec (about 220 km/h) vertical velocity in the ideal “rough braking phase” of 690 seconds, during which the lander will descend from an altitude of 30 km to 7.42 km. During this time, the lander will travel a distance of 713.5 km across the surface of the Moon towards the landing site.

At a height of 7.42 km from the surface, the lander will go into an “attitude hold phase” lasting around 10 seconds, during which it will tilt from a horizontal to a vertical position while covering a distance of 3.48 km. The altitude will be reduced to 6.8 km, and velocity to 336 m/sec (horizontal) and 59 m/sec (vertical).

The third phase of the landing process, the “fine braking phase”, will last around 175 seconds, during which the lander will move fully into a vertical position. It will traverse the final 28.52 km to the landing site, the altitude will come down to 800-1,000 m, and it will reach a nominal speed of 0 m/sec.

“From 30 km to 7.42 km (altitude) will be rough braking and at 7.42 km there will be an attitude hold phase where some of the instruments will carry out calculations; at 800 or 1,300 metres (altitude) it will start doing a verification of the sensors, at 150 metres (altitude) it will do a hazard verification and decide whether it should land vertically there itself or move laterally to a maximum extent of 150 metres to avoid any boulders or craters,” Dr Somanath said.

Four phases of the Chandrayaan-3’s descent

It was between the “attitude hold phase” and the “fine braking phase” — before the Chandrayaan-2 lander could enter the final “terminal descent phase” — that it lost control and crashed. ISRO has used studies of the failure to improve the landing chances of Chandrayaan-3 to a higher degree.

* In Chandrayaan-2 a first-order automated guidance system was used in the first rough braking phase; in Chandrayaan-3 a second-order guidance system is being used. In Chandrayaan 3 an instantaneous thrust regulation is also used in the rough braking phase.

* In Chandrayaan-3, the thrust demand is at a higher level of 740X4 N during the second attitude hold phase instead of the 400×4 N in Chandrayaan 2 to ensure thrust continuity at the start of the second phase of landing. The new systems will facilitate thrust and angle continuity for the lander as it manoeuvres from a horizontal to a vertical position.

“Extensive simulations have been done, the guidance designs have been changed, a lot of the algorithms have been put together to ensure that the required dispersions are obtained in all these phases. Even if there are variations in the nominal numbers still the lander will make an attempt at a vertical landing,” Dr Somanath said.

“If all sensors fail, if everything fails, it will still make a landing provided the propulsion system works well. This is how it has been designed. Even if two of the engines do not work, this time the lander will be able to land. It has been designed in such a way that it should be able to handle multiple failures. If the algorithms work well we should be able to do a vertical landing,” he said.

Slower, lower, closer

The lander can touch down at a maximum speed of 3 m/sec (10.8 km/h) without endangering the instruments on board, but the optimal speed is around 2 m/sec (7.2 km/hr). The lander can also have a tilt up to 12 degrees and still land safely.

“Although 3 m/sec looks like a low speed, if a human falls at that speed all our bones will be crushed. [But] it is a speed we can guarantee with our sensors and measurements. Attempting to land at ultra low speed also requires a lot of fuel, and theoretically, there has to be some velocity to touch down and this has been identified as 1 m/sec. System is however built to handle velocity of up to 3 m/sec,” the ISRO chief said.

Dr Somanath had said recently that the landing speed threshold, which was originally 2m/sec (7.2 km/hr) with a small margin of increase, had been increased subsequently. “We have created energy absorbing capability,” he had said.

Once the lander settles on the Moon, it will release a rover on board to take pictures of the lunar surface and conduct experiments with two onboard instruments.

In 2019, the anomaly that occurred during the second of the four phases, was reflected in the computer systems at Mission Control, but scientists could not intervene because the lander was in an autonomous mode, using data fed into its system before the start of the powered descent. ISRO is now confident that the errors have been corrected for the Chandrayaan-3 mission.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05