#arseniclife: Story of a viral study & a contentious retraction

While there is broad scientific consensus against the study’s findings, the retraction nonetheless is contentious, and potentially opens a pandora’s box for academic publishing.

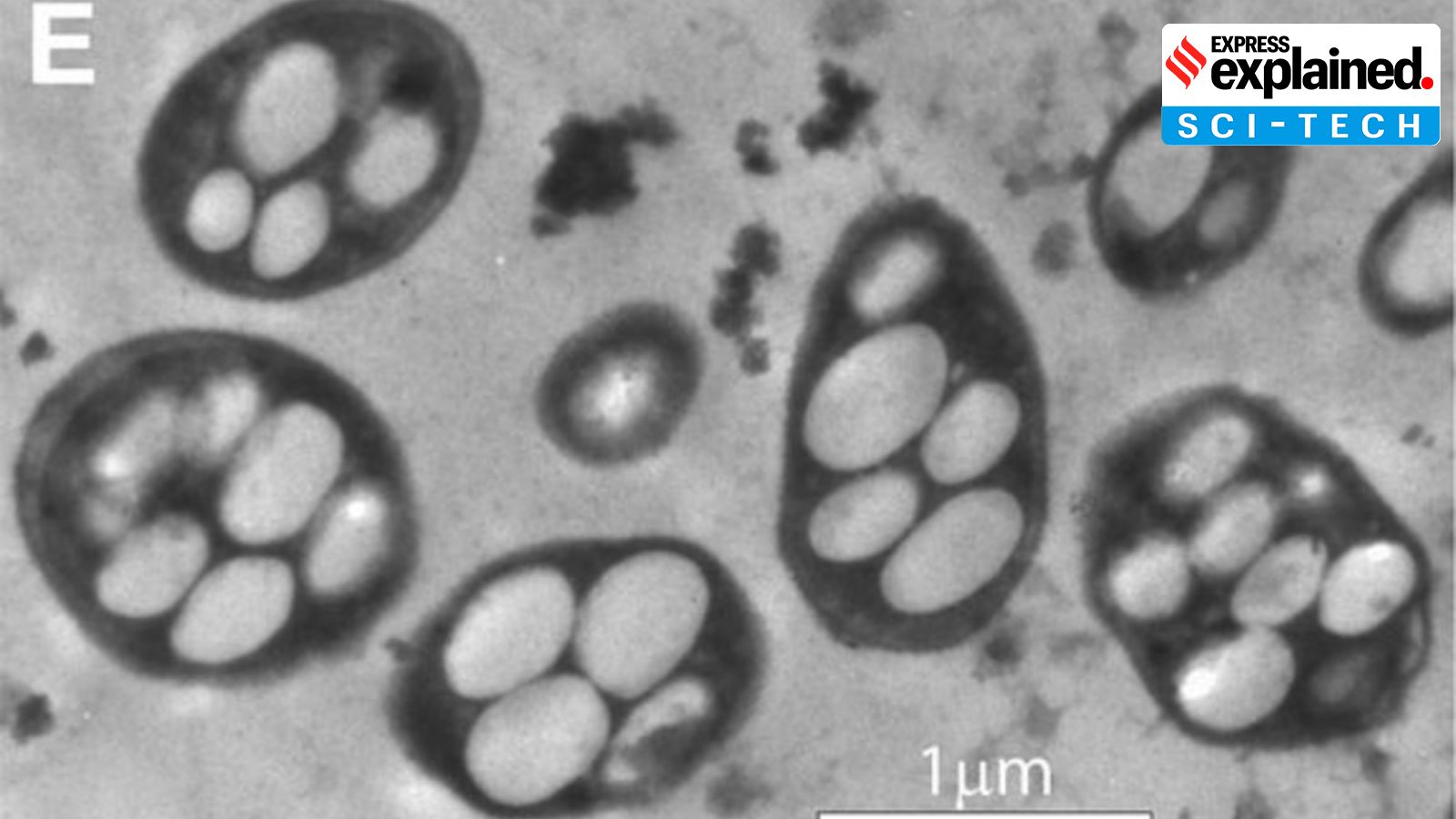

Transmission electron micrograph shows a strain of the bacterium called GFAJ-1, which researchers claimed can incorporate arsenic into its DNA and other vital molecules, in place of the usual phosphorus. (Science)

Transmission electron micrograph shows a strain of the bacterium called GFAJ-1, which researchers claimed can incorporate arsenic into its DNA and other vital molecules, in place of the usual phosphorus. (Science)Fifteen years ago, a group of scientists made the bold claim of having discovered a microorganism that could survive using chemistry different from any known life-form. On Thursday, the journal Science, where these findings were reported, formally retracted the 2010 paper, saying it was fundamentally flawed.

While there is broad scientific consensus against the study’s findings, the retraction nonetheless is contentious, and potentially opens a pandora’s box for academic publishing.

Why study went viral

Living beings typically rely on a number of common elements, including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur, to build biomolecules such as DNA, proteins and lipids.

In 2009, researchers collected a microbe from Mono Lake, a salty and alkaline body of water in California. In the lab, they claimed to have found that this microbe could replace phosphorus with arsenic, an element that is typically toxic. Phosphorus is essential to the structure of DNA and RNA and to the function of the energy-transporter molecule ATP.

If confirmed, the discovery would change scientists’ fundamental conceptions about life on Earth, and possibly beyond. Naturally, the study received a lot of attention, and travelled well beyond the typical terrain of academic conferences and scientific journals.

Many scientists around the world expressed serious concerns with the study’s methodology and conclusions. Most notably, the discovery was picked up by the Internet. On the then nascent Twitter, it trended with the hashtag #arseniclife. The study’s authors also faced extreme scrutiny into their personal lives.

Why retraction is contentious

Science has not accused the paper’s authors of misconduct or fraud, and instead cited its latest standards for retractions, which allow it to take down a study based on “errors” by the researchers. The decision was made after The New York Times last year reached out to Science for a comment on about the legacy of the #arseniclife affair.

That inquiry “convinced us that this saga wasn’t over, that unless we wanted to keep talking about it forever, we probably ought to do some things to try to wind it down,” Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of Science since 2019, told The NYT. “And so that’s when I started talking to the authors about retracting.”

But the paper’s authors disagree with the decision. Their defenders, including officials at NASA, which helped fund the original research, say the move is outside the norms of what usually leads to the striking down of a published paper.

Ariel Anbar, a geochemist at Arizona State University and one of the paper’s authors, has said that the data itself is not flawed, and if disputes about “data interpretation” were acceptable standards for retraction, “you’d have to retract half the literature”.

As justification for the retraction, the Science statement cites the technical objections published alongside the paper, and failed replications of the findings in 2012. But the original paper’s authors have responded to the objections and criticised replication experiments. Anbar has accused Science of not providing any “reasonable explanation” for the retraction.

Ivan Oransky, a specialist in academic publishing, told Nature that this retraction raises an interesting question. There are plenty of debunked papers in the literature that could be retracted, he says. Will other publishers get on board with trying to clean up the scientific record? And if so, “where do you start?”

INPUTS FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05