The ruling overturned the Supreme Court’s September 2021 judgment that upheld the arbitral award. A month after the 2021 judgment, the court had dismissed a plea seeking a review — the final step in the appeal process after which a ruling of the highest court attains finality.

The court has now exercised its “extraordinary powers” in a curative writ petition to correct a “fundamental error” in its judgment.

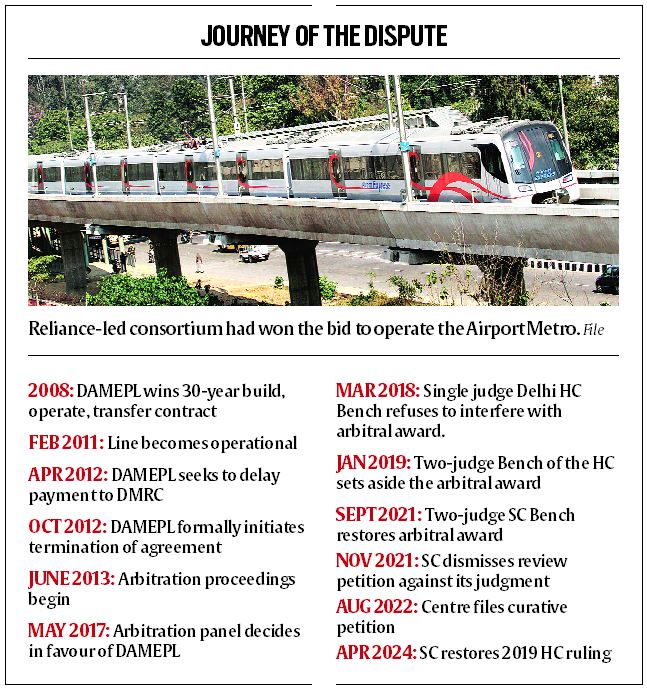

History of the case

In 2008, the DMRC entered into a public-private partnership with DAMEPL, a consortium led by Reliance Infrastructure Ltd, for the construction, operation, and maintenance of the Delhi Airport Metro Express. While DMRC acquired the land and bore the cost of construction, the consortium was to design, install, and commission the railway systems in two years. Thereafter, until 2038, DAMEPL was to maintain the line and manage its operations, while paying a “concession fee” to DMRC.

However, a year after the line became operational, the consortium asked DMRC if it could defer payment of the concession fee. Among the reasons cited were delays in providing access to the stations by DMRC, and that retail activity had not picked up on the line. This triggered a dispute between the consortium and the Union Ministry of Urban Development.

Subsequently, barely a year into its operations, the line was shut following a complaint from DAMEPL that it was “unsafe to operate”. The consortium triggered a termination of its agreement alleging there were technical problems in the civil structure of the Metro corridor, for which DMRC was responsible as per the agreement.

Before operations were finally handed over to DMRC in June 2013, DAMEPL and DMRC made a joint application before the Commissioner of Metro Railway Safety for reopening the line. While the line started functioning again, the government and Reliance began a battle before an arbitration tribunal for losses due to cancellation of the agreement.

Rulings of courts

Story continues below this ad

In 2017, the panel of three arbitrators decided in favour of Reliance and ordered DMRC to pay nearly Rs 8,000 crore. This included termination payment of Rs 2,782.33 crore, interest to the tune of 11%, bank guarantees, and expenses incurred in operating the Metro for a few months between the decision to terminate the agreement and the date on which operations were handed over to DMRC.

When the consortium sought to enforce the award, DMRC moved the Delhi High Court. A single judge Bench of the HC refused to interfere with the award, and directed DMRC to deposit 75% of the award in an escrow account.

The government then moved an appeal before a two-judge (division) Bench of the High Court. In 2019, the division Bench overturned the arbitral award, ruling in favour of DMRC. The Bench held that the tribunal had not considered some key facts, and had left some ambiguity in interpreting when the termination of the agreement took place.

This led DAMEPL to approach the Supreme Court against the High Court verdict. The SC heard the case, and in September 2021 reversed the HC verdict. A Bench comprising Justices L Nageswara Rao and S Ravindra Bhat underlined that courts must exercise restraint when interfering with arbitral awards.

Story continues below this ad

This is crucial, since arbitration is an institutionalised alternative form of dispute resolution. It is devised and regulated by a 1996 statute to ensure speedy disposal of cases, especially commercial matters which suffer due to delays in the judicial system. The legislation and a plethora of SC judgments underline this aspect of minimum judicial interference with arbitral awards.

In November 2021, the SC dismissed a review petition against its judgment. Almost eight months later, DMRC filed a curative writ petition, the last resort to correct a judgment of the Supreme Court.

Curative jurisdiction

A curative writ petition as a layer of appeal against a Supreme Court decision is not prescribed in the Constitution. It is a judicial innovation, designed for correcting “grave injustices” in a ruling of the country’s top court.

The SC first articulated the concept of a curative writ in Rupa Ashok Hurra vs Ashok Hurra (2002). If there was a significant miscarriage of justice due to a final decision of the Supreme Court, could the court still correct it? One the one hand was the issue of finality and closure to a case, and on the other hand was the substantive question of rendering justice in its true sense. In answering this question, the SC said that its “concern for rendering justice in a cause is not less important than the principle of finality of its judgment”.

Story continues below this ad

However, curative writs are sparingly used. There are narrow, mostly procedural grounds that permit the filing of a curative writ. A claim must be made that principles of natural justice were not followed — for example, that a party was not heard, or that a judge was biased, or had a conflict of interest. These petitions need to be approved by a senior advocate designated by the court.

Curative writs are filed mostly in death penalty cases. The SC in the Yakub Memon case (2015) and the Delhi gang rape convicts case (2020) dismissed curative writs challenging death sentences. In 2023, in the Bhopal gas tragedy case, the SC refused to exercise its curative powers to enhance the compensation provided to victims that was deemed grossly inadequate.

After the judgment

The restoration of the 2019 position means that DMRC does not have to pay the arbitral award. About Rs 2,600 crore that DMRC had deposited with the High Court in an escrow account will be restored.

Allowing a curative petition at the government’s instance almost two and a half years after its final verdict marks a significant moment in the way the court has exercised its vast powers. Lawmakers often argue for judicial restraint, especially with regard to the exercise of powers that the court has given to itself by going beyond the letter of the Constitution. While the government had high stakes in this case, such exercise of the curative jurisdiction could have a bearing on investor confidence.

Story continues below this ad

Justices Rao and Bhat who delivered the 2021 verdict and dismissed the review are now retired.