Independence Day: The lead-up to Indian independence, from a British perspective

Independence was a seminal moment in Indian history. It was also a seminal moment in British history, ending two centuries of British dominance in the world.

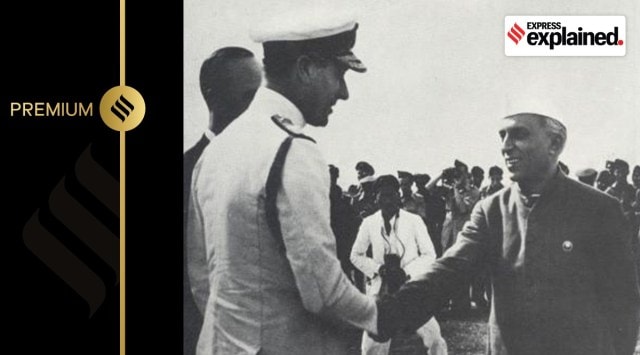

Nehru receives Mountbatten. Upon arriving in India, Mountbatten decided that a quick, immediate exit was the best way to “avoid further bloodshed” in the subcontinent. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Nehru receives Mountbatten. Upon arriving in India, Mountbatten decided that a quick, immediate exit was the best way to “avoid further bloodshed” in the subcontinent. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) At the stroke of the midnight hour, on August 15, 1947, British rule in the Indian subcontinent came to an end. A bittersweet culmination of decades of struggle for independence, the day was a seminal moment in Indian history, with far reaching consequences, felt even today.

It was also a seminal moment in British history, heralding an end to the once indomitable British Empire. As Lord Randolf Churchill, father of Winston Churchill, had once said: “The loss of India would mark and consummate the downfall of the British Empire … From such a catastrophe there could be no recovery”.

Catastrophe or not, the Empire did indeed crumble post 1947. Between 1947 and 1965, the number of people under British rule outside the UK fell from 700 million to merely five million, three million of whom were living in Hong Kong (which Britain handed over to China in 1997).

As we observe the 77th anniversary of Indian independence, a closer look at what led to Indian independence – and the eventual decline of the Empire – from the British perspective.

Economic crisis following World War II

While Britain emerged victorious from World War II, it was physically and financially exhausted.

Its treasury was nearly empty by 1945, and it had mounted significant war debt. At the same time, Britain was in dire need of resources to rebuild itself following the war. Rationing was still on due to food shortages, there were severe labour shortages, and British towns and infrastructure were in tatters.

The situation was ripe for some radical changes – decolonisation was an obvious outcome. Simply put, Britain did not have the resources to maintain its global empire any more. As economist John Maynard Keynes argued post-war, “the only solution [to address Britain’s economic predicament] was to drastically cut back the spending on the British Empire.”

Clement Atlee and his Labour Government

During the War, Britain was led by Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Though hailed as a great war time leader in Britain, Churchill was out of his depth when it came to handling the fallout of the War. The 1945 general elections ousted Churchill’s Conservative Party and brought in a new Labour Party government.

The government was led by Clement Atlee, in many ways, Churchill’s diametric opposite. Atlee was a shy, almost uncommunicative, figure compared to Churchill’s boisterous personality. Crucially, he also shared very different views on the British Empire than Churchill.

Winston Churchill, for all his war time leadership against fascism and Hitler, was very much an apologist for the Empire. He was against giving Dominion status to India in 1930, and by the War, even though he had shifted his stance, he still did not support full independence.

In fact, many have argued that he was directly to blame for the Bengal Famine of 1942. As Leo Amery, Secretary of State for India under Churchill remarked, “On the subject of India, Winston is not quite sane”.

Atlee, on the other hand, was firmly in favour of “self-governance” in India, a sentiment he had expressed as far back as the early 1930s. Not only would this free up resources for the massive welfare push he had planned for Britain, Atlee also felt that not granting independence, in the face of rising nationalist fervour, would only further make things worse.

“The demand for self-government has been insistently pressed for many years by the leaders of political thought in India … Delay in granting it has always led to more and more extreme demands.,” he said during a speech in the House of Commons in 1947.

Remember, this is also the time where the “red scare” was very real. Leaders in the West were deeply concerned with the possibility of communist uprisings elsewhere. In India, strikes and workers’ demonstrations added to this fear.

Mutiny in the Royal Indian Navy

Perhaps one of the final nails in the coffin of the British Empire was a massive mutiny in the Royal Indian Navy in 1946. While independence was pretty much certainty by this time, scholars argue that the Mutiny “expedited” the British exit from India.

The RIN had exponentially expanded during the War, as the Royal Navy itself was otherwise occupied. The nascent naval force performed admirably during the War, and was crucial to the recapture of Burma from the Japanese.

But with the War over and Britain’s coffers empty, demobilisation of the RIN was perhaps as swift as its mobilisation. Thousands of ratings (British term for non-commissioned sailors) were let go with little recognition and even lesser remuneration. For those who were kept on, working conditions were poor and racism pervasive in the leadership.

Consequently, nationalist fervour also swept through the ratings, especially during the highly public Red Fort trials against officers of the defeated Indian National Army. Thus, between 18 to 25 February, 1946, the mutiny spread from Bombay to Karachi and Calcutta, eventually involving over 20,000 Indian personnel and 78 ships and shore personnel.

While the mutiny did not last long, it convinced the British that they had to grant India independence – and fast – reminding them of their rapidly losing grip over the country.

Atlee announced The Cabinet Mission a day after the mutiny started.

Britain’s “early” exit and the Partition

While Atlee was clear that India’s independence could not be delayed, what was less clear was exactly what independent India would look like.

The Cabinet Mission under Pethick-Lawrence, Strafford Cripps, and AV Alexander, alongside then Viceroy Archibald Wavell, proposed a complicated three-tier administrative structure for India, with a weak central government. The Mission felt this would allow India to stay united while assuaging Jinnah’s demands for a separate Muslim state.

However, this proposal was eventually rejected by both the Congress and the Muslim League. This rejection also unleashed a wave of communal violence and worsened the already tenuous law and order situation in the country, especially in Bengal.

Atlee decided to replace Wavell with the charismatic Louis Mountbatten in February 1947 and told him, “Keep India united if you can. If not, save something from the wreck. In any case, get Britain out.” A day prior to appointing Mountbatten, on February 20, Atlee had announced in the House of Commons that British rule in India will end “not later than July 1948”.

However, upon arriving in India, Mountbatten realised that waiting till July of next year would possibly not be wise in light of the already worsening situation. Against the advice of senior British administrators, Mountbatten decided that a quick, immediate exit was the best way to “avoid further bloodshed” in the subcontinent.

Of course he failed in this intended goal. Where he did succeed, however, was in ensuring that Britain did not get caught up in the chaos. As C Rajagopalachari, had once remarked about Mountbatten’s decision, “If he (Lord Mountbatten) had waited till June 1948, there would have been no power left to transfer.”

The plan for India’s independence and partition was announced on June 3, and the Indian Independence Act received royal assent on July 18. The “Mountbatten Plan” as this was known, set August 15 – the second anniversary of the Japanese surrender – as the deadline for transfer of power.

While for Empire apologists, August 15 was indeed a day of mourning, of great loss, most of the British public had more pressing domestic concerns to deal with. In the end, Britain successfully managed to extricate itself from the mess it had a huge hand in creating.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05